The View

EditorialAboutA+a Study CentreA+a ArchiveShopClose Menu

Bernard Smith's polemical and groundbreaking Boyer lectures in 1980, 42 years ago, issued a wake-up call to the Australian nation and especially its artworld. There was a 'moral imperative', he said, for the Australian nation to open what he called ‘the locked cupboard of our history’, calling it the ‘historical drama’ of our times. It’s fair to say that his journey towards this position began with this book, European Vision and the South Pacific.

He began thinking about it immediately after World War Two, in the wake of his book written during that war, Place, Taste and Tradition (1945), which against the reigning paradigm of the time, proposed that Australian art was born from colonial or empire art not its rejection. Its Bernard’s single greatest insight. To prove it, he wrote European Vision (1950) with a scholarly acumen beyond reproach. European art museums are only just catching up with the case it makes for Europe’s national art histories originating in colonialism.

This scholarly acumen along with what he discovered has made European Vision his greatest book and why a third edition is being published now some seventy years after he first sketched out an argument that opened the door to what we in the academy call postcolonial critique. Indeed, it’s become commonplace to compare it to Edward Said’s acclaimed Orientalism (1978), of which it was some twenty years in advance. More importantly, the agency it gives to the Pacific in revolutionising European knowledge systems was a postcolonial-type revision of Orientalism before the fact.

The weakness of European Vision is that this agency doesn’t go far enough, being limited to the European reception of the Pacific. Nevertheless, it triggered a greater appreciation of the transcultural exchange between Europeans and indigenous people of the regions by later scholars evident in the new introduction of this third edition, in which the Indigenous art historian Greg Lehmann acknowledges the profound influence of European Vision.

The scholarly rigour and tone of European Vision and its supplements—the volumes he produced in the 1980s on the art of Cook’s voyages and the first British penal colony in Australia—sit uncomfortably with Bernard’s natural gait, which was as a polemicist. He was an activist, a communist no less, in which his scholar’s gown was a poor disguise.

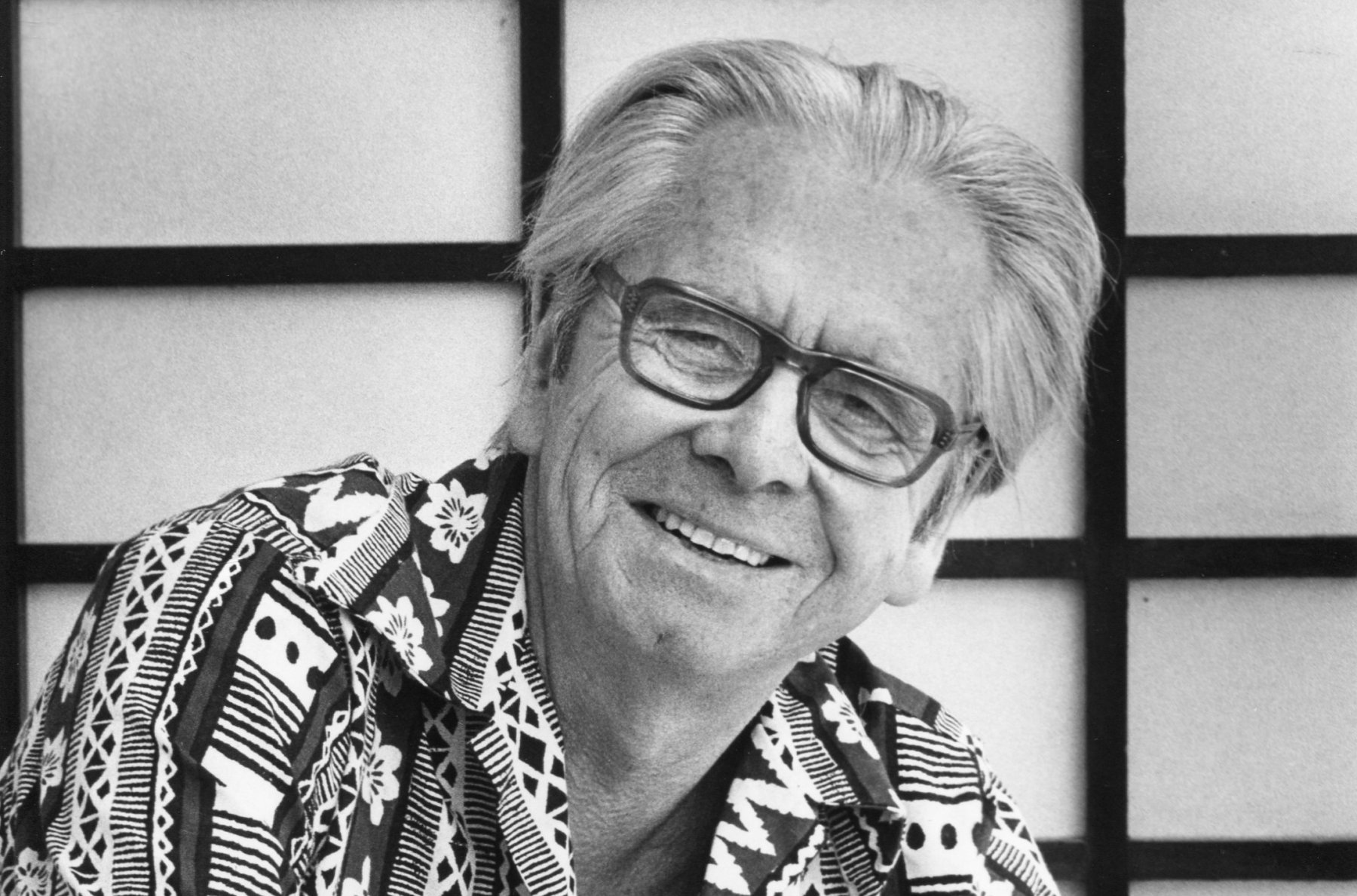

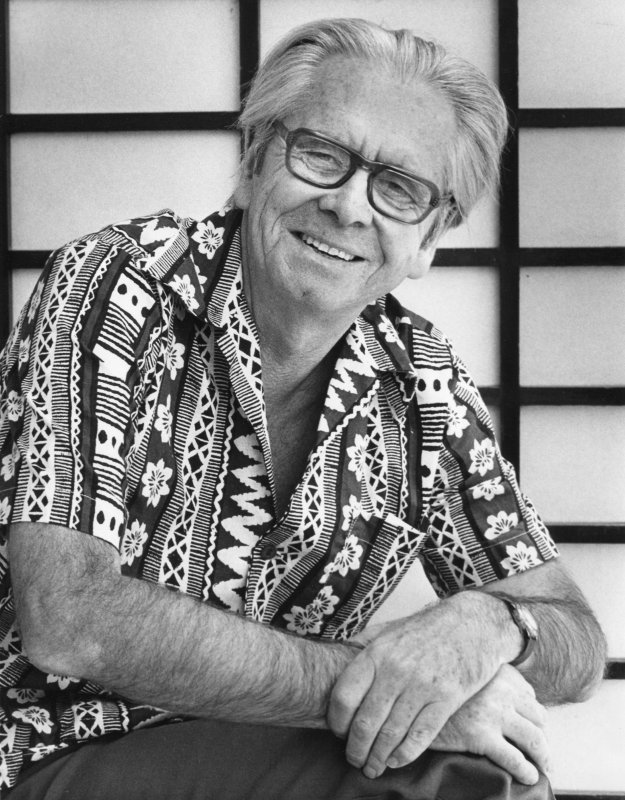

This third edition of European Vision owes a great debt to Sheridan Palmer who co-authored, with Greg Lehmann, the new introduction. Thanks to her finely crafted biography of Bernard Hegel’s Owl: The Life of Bernard Smith (2018), we know more than we need to about Bernard—though as she pointed out, quoting Luke Slattery, Bernard was ‘an unbridled revealer’ with ‘a mania for self-disclosure’. Slattery was referring to Carmel O’Connnor’s large Archibald portrait of the 86-year-old Bernard in the dress of the Barberini Faun, legs wide open, genitals planted in the centre of the painting. Throwing his academic gown aside to reveal all, Bernard cast himself as Dionysius triumphantly stamping on three academic tomes with his left foot, of course. On the wall behind hangs a landscape painting.

One of several jokes in this very naked nude is its classical idealisation, as if the wiry Bernard regularly pumped iron and had just returned from a hard work out in the gym. Wedded to the cause of realism and the demystification of ideology, Bernard never lost sight of the ironic structure of Hegel’s dialectic, which warns us that even at its most naked, the empirical drive of realism is embroiled in the ideological dress of nudity. It is a clue to what lies beneath the scholarly quest of European Vision to prove empiricism’s revolutionary credentials.

Sheridan shrewdly locates the drive of Bernard’s intellectual questing in the emotional homelessness stemming from being a foster child with his bastard ancestry vaguely apparent from fleeting impressions of his mother and father. Bernard, she argues, was obsessed with the question of origins and home because this is what he lacked. It gave Bernard an insight into the Australian settler psyche.

The impact of childhood experiences on one’s worldview is a truism of modern psychology, but animist knowledge systems give priority to the place of one’s conception, a place to which one must also return. We know from Bernard’s autobiographies that this was the distant tropical city of Far North Queensland, Cairns, where his parents had worked as the gardener and maid in a well-to-do household. But when eighteen-years-old Bernard returned to visit his mother and step siblings, he was shocked by the rude existence and intellectual deprivation of their lives. Steeped in Darwin and soon Marx and Freud, this up-and-coming intellectual quickly retreated back to his life of the mind, making his home in the adopted cultural capitals of Sydney and Melbourne.

Darwin, Marx and Freud each wrote origin stories. European Vision is essentially an origin story that takes its inspiration from Darwin’s discovery of evolution in the Pacific, where everything seemed so radically different, so antipodal to existing European cosmology. At a deeper psychic level, it is a second more successful return to his conception site in exotic climes far from his digs in the southern capitals. Here he discovered a new genre, empire art, which he divided into two parts. One was produced according to the empirical precepts of the sciences under the auspices of the Royal Society. The other was found in the formalism and idealism taught in the Royal Academy that promoted the ideological values of British Imperialism from which Australian art, he argued, had to escape. His tracing of the demise of the academic classical tradition and the rise of modernism and Australian art from the same dialectic that echoes in his uncanny antipodean consciousness in search of a home, a national tradition. If in Australian Painting Smith argued, to quote, that ‘Australian artists have constantly returned to refresh themselves from the deep fountains of European culture and civilisation’, European Vision shows that colonialism rearticulated these fountains with water drawn from the deep fountains of the Pacific.

Author/s: Ian McLean

Ian McLean. 2022. “Launching Bernard Smith's European Vision.” Art and Australia 58, no.1 https://artandaustralia.com/58_1/