The Mirror

EditorialAboutA+a Study CentreA+a ArchiveShopClose Menu

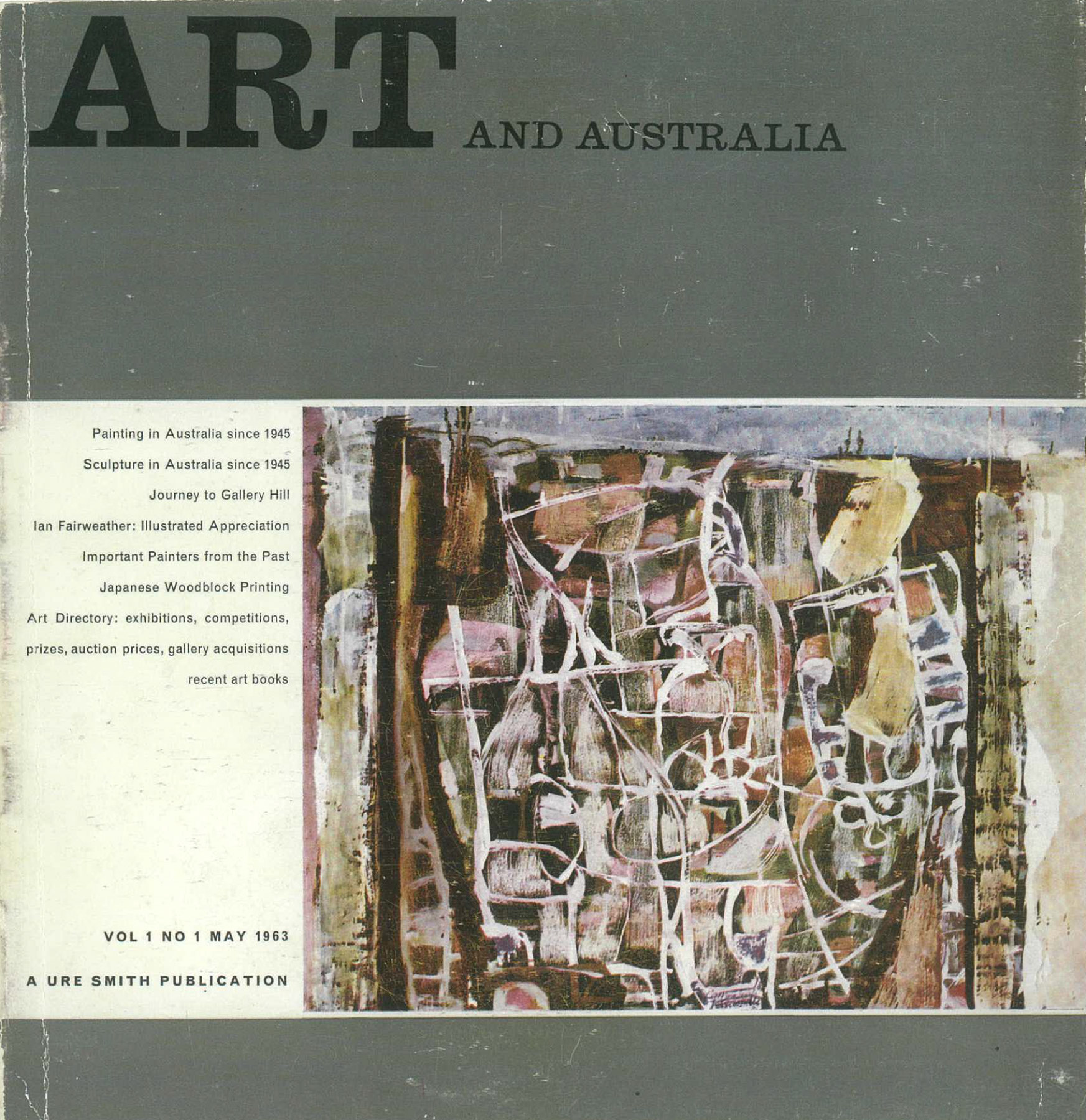

On From the Archive we will temporarily republish key articles from the Art + Australia Archive dating back to 1963. The Art + Australia Archive is a valuable resource of discussions and debates about art, artists and exhibitions that have shaped Australian art.

You can get full access to the Art + Australia Archive by subscribing here.

Art and Australia Vol 48.1, 2010

At the birth of the modern environmental movement in the 1960s, the truly destructive aspect of humankind's engagement with nature was difficult to imagine. In her 1962 book Silent Spring, biologist Rachel Carson warned against the threat of environmental disaster in the following terms: 'A grim spectre has crept upon us almost unnoticed, and this imagined tragedy may easily become a stark reality we all shall know.' Today the imagined tragedy appears to have crystallised as we find ourselves in a state of crisis whose most recent harbinger is that of the spectre-like oil slick creeping its way across the Gulf of Mexico. Science tells us with increasing certainty that we are indeed destroying our planet, and this realisation throws us into a paralysing dialectic of action and inaction—we accept that we must act and yet we do not. From the 'imagined tragedy' of 1962 to the crushing contemporary reality, the history of the environmental movement reveals a troubled lurching between the imagined and the real. How can we achieve a more harmonious balance?

Bonita Ely is an artist whose work over the past forty years has carefully traced a series of answers to precisely this question. Through her work as an installation and performance artist, a feminist and a teacher, Ely has had a decisive influence on the history of Australian art. Indeed, her influence continues to spread through her role as Head of Sculpture, Performance and Installation at the University of New South Wales's College of Fine Arts in Sydney. But it is through her engagement with the ecological, starting with her earliest works and continuing today, that Ely's importance can be most keenly understood.

Ely's ecology project began in the 1970s as part of the rising dominance of installation art. C20th mythological beasts: at home with the Locust family, 1975, was an assemblage of three marionette-like figures lolling in a suburban lounge room. The work recalled the disturbing installations of American Edward Kienholz, but with an organic inflection: the sculpted carpet was grass-green, the sofa swelled bulbously around the figures, and the walls were pasted with blue floral wallpaper. The family sat facing a television showing slides of beautiful New York sunsets—aglow with the cocktail of pollutants lacing the Manhattan air. Viewed as a whole, the work presented an ironic critique of decadent modern living, something the artist had experienced during a stay in booming post-industrial New York in the early 1970s. More pointedly, however, the grotesquery of modern life was intrinsically linked here to a corrupt cooption and emulation of nature— the grass-like carpet, the banal repetition of the floral wallpaper and the hybrid insect-human forms of the figures themselves. For Ely the emergence of modern life coincided with the decay of the romantic vision of nature. She staged this moment of decay as a grotesque farce in which it was no longer possible to distinguish between the human and the non-human, the beautiful and the obscene.

Ely's other key work from the period was Mt Feathertop project, 1979. Focusing on this mountain peak in the Victorian Alps, the installation comprised watercolour views in different seasons, a papier-maché scale model and a collection of documents describing the mountain's ecological destruction by humans. Mt Feathertop marked Australian installation art's centring on the environmental and the local, with the piece comparable to contemporary works by artists such as Kevin Mortensen, Ross Grounds and John Davis. All exhibited during the 1970s at the Mildura Sculpture Triennial, where parts of Mt Feathertop were first shown in 1975. As Ely later noted, the work represented an attempt to know the mountain, to understand its seasonal changes, its topological structure and its environmental decay, with the artist's dedication to the work over a number of years rendering the project a tender 'homage' to place. As with Locust family, the work was also tempered by a subtle irony, for in presenting the mountain as a series of interlocking rational systems of knowledge, Ely also pointed to what was ultimately missing from the work: an encounter with the mountain itself. Where Locust family critiqued the decay of the romantic ideal of nature, Mt Feathertop revealed the flaws in its scientific rationalisation.

Ely's early environmental art was intertwined with the concurrent rise of feminist theory in Australia. The 1970s saw the establishment of the Women's Art Forum, the Lip Collective and, following a visit from the feminist art historian Lucy Lippard in 1975, the Women's Art Register—all of which involved Ely to some degree. Ely's most important impact at this time was her work on the register with Anna Sande, collecting records of female artists from around Australia and advocating strongly for the inclusion of women's art practices in educational institutions. This push for an increased agency for women in the 1970s demanded new forms of artistic expression. For artists such as Ely, Jill Orr and Joan Grounds, these new forms were to be found through an immersion in the primeval materials and symbolics of nature and their activation through ritual and performance. This immersion allowed engagement with nature not as a distant sacred object but as a deeply personal—and thus deeply feminine—encounter. Furthermore, this strong empathy with the earth rendered its destruction a terrible and personal violence. In her performance Jabiluka voz, 1979, Ely employed spiral forms and simple materials—sand, fire and straw—to ritualise the great violation that uranium mining in the Northern Territory was having on both the land and its Indigenous people.

The 1980s, however, brought a more sceptical attitude towards gender and ecology, and the conflation of woman and nature in performances such as these began to be seen as naive. The guilty party, it was argued, was surely the act of representation itself. Ely captured this moment of radical scepticism in what is perhaps her most influential and incisive piece, Murray River punch, 1980. In this work the artist, elegantly dressed as a kitchen hostess, demonstrated her special recipe for replicating the 'renowned flavour' of the Murray. The ingredients that were mixed together before increasingly incredulous crowds at Adelaide's Rundle Mall and the University of Melbourne included water, urine, human faeces, fertiliser, agricultural chemicals and a finishing garnish of rabbit dung. With delicious dry humour, Ely's performance gracefully wove together critiques of female stereotyping, human exploitation of the environment and the colonial-pastoralist appropriation of land. Yet the work's subversive intelligence lay in the substance of the punch itself. Underneath her ironic critique of dominant representational structures, Ely smuggled in an unexpected encounter with the real—the acrid smell of phosphate, the stench of human faeces. Murray River punch forced viewers to confront both the imaginary and the reality of nature: the ideological structures that frame its exploitation and the undeniable physical degradation this exploitation brings about.

Ely's concern for the ecology of the local, and of the Murray in particular, has not lessened over the years. In two recent bodies of work, 'Murray River Series' (2008) and "Drought: The Murray's Estuary" (2009), she presented a series of photographs taken along the Murray from the headwaters of the river near Mount Kosciuszko to the river's mouth at Lake Alexandrina. The artist's documentation of the river was extensive and systematic. At certain locations she created 'sample grids' by winding string around pieces of wood and then photographing the contents of each square along the grid. This observational process referred back to Murray Rivers Edge, a 1977 series of photographs of the same locations. Where the earlier sample grids bore witness to a river plagued by high salinity and the depletion of the river red gum stands, in the 2008-09 work we additionally see bluegreen algae, acid sulphatecontamination and drought. One sample grid, taken near the Barmah Forest in northern Victoria, frames a receding shoreline: in one section a beer bottle lies encased in the mud, in another the artist's boot protrudes into the shot.

Read together, the 1977 and 2008-09 works paint a clear picture of environmental decline. They gesture towards the current environmental crisis, not as a sudden moment of grand and epic disaster, but as a series of small accruing material realities. But more importantly, and as the intruding boot signifies, these works provide a framework through which the human can approach and confront these consequences. Within this framework, nature is not a distant space of auratic beauty, but a realm of personal encounter in which, looking down at the foot, viewers see themselves as but one material being among many.

It may well be that the current state of ecological crisis will soon replace globalisation as the dominant cultural condition. In contrast to globalisation, which emphasises the invisible and the infinite, the state of environmental crisis drags us back to earth to contemplate the material and finite. It demands that artists and non-artists alike reassess the way in which they engage with the natural world- both at a real and an imaginary level. Over the course of her career, Ely has discovered such a mode of engagement. It is not to be found, she suggests, in the romantic visions of nature as a sacred object, nor as an imbrication of rational data. Rather, it is to be sought in a state of personal encounter with the materiality of the earth itself. Ely's work suggests that by holding this type of encounter in a state of suspension, either through the use of irony or self-reflection, the unthinking paralysis we currently face can be transformed into its much more positive other—a moment of thoughtful connection.

1. Janine Burke, Field of Vision: A Decade of Change - Women's Art inthe Seventies, Viking, Melbourne, 1990, p. 93

2. This idea is derived from the work of the contemporary theorist Timothy Morton in his book Ecology Without Nature: Rethinking Environmental Aesthetics, Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Mass., 2007. See also Jane Bennett, Vibrant Matter: A Political Ecology of Things, Duke University Press, Durham, 2010.

Full Art + Australia Magazine Archive

Bonita Ely's Art Of Ecology : Nicholas Croggon

. “From The Archive.” Art and Australia.com https://artandaustralia.com/A__A/pp94/from-the-archive