Like a Fog

This essay is a backgrounder to the forthcoming ABC Indigenous documentary series, Tracking Emu.

For an unknown time - but certainly for long before the arrival of white people – Aboriginal people had used the lands where the tests took place… people were constantly traversing the country. [1]

The explosion lit the whole of the desert many times more brilliantly than the fiercest sunshine. The trees and plants dotted across the desolate tableland would transform suddenly from olive green to a violent livid shade. And those who had dark glasses saw rising above where the tower had been a frightening ball of fire ... [2]

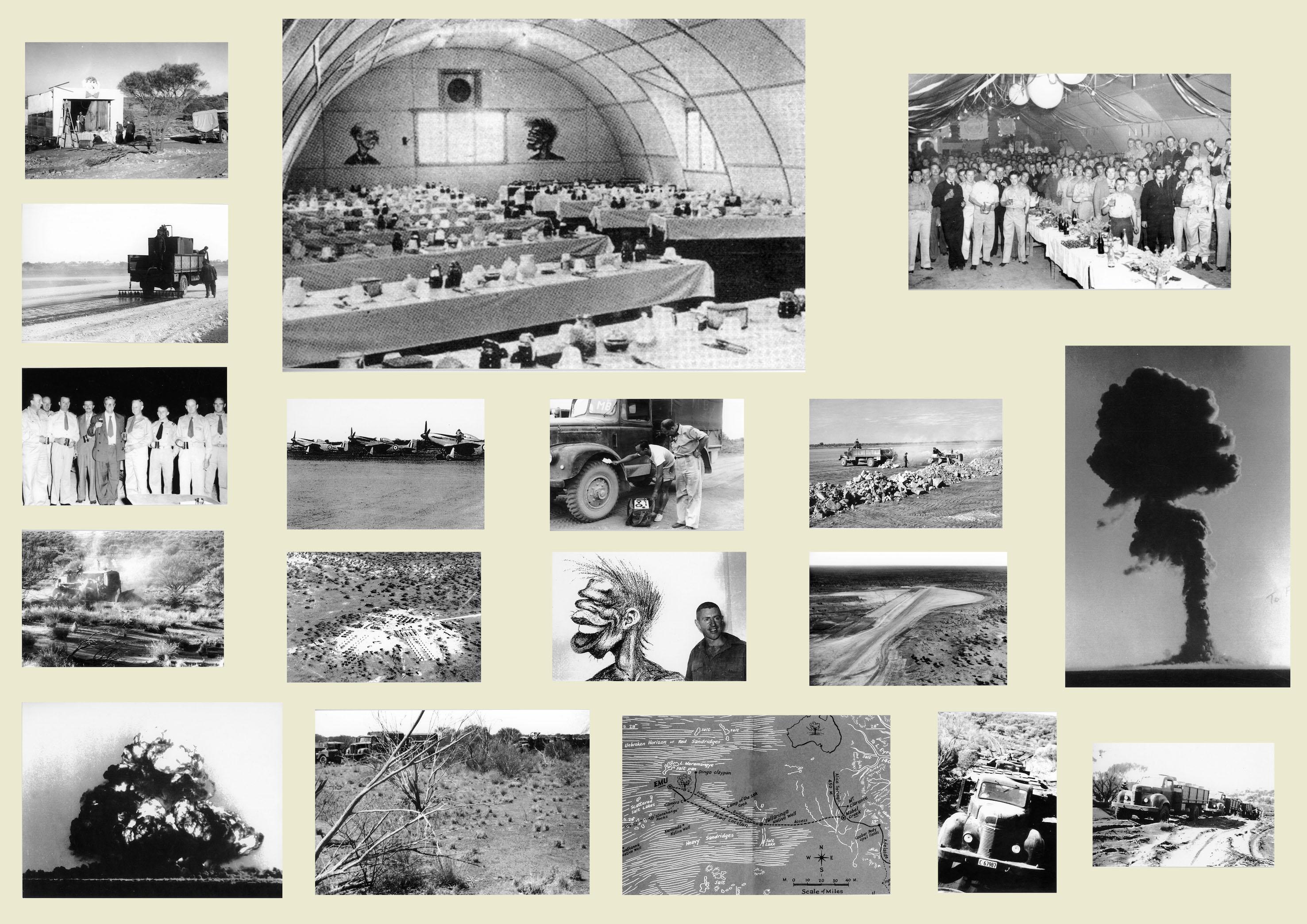

The term Maralinga—itself a geographically and culturally distant borrowing—often captures the entire British nuclear program on the Australian mainland. Yet the first test was conducted 100 kilometres north of the vast prohibited zone known as Maralinga, in a remote claypan west of Coober Pedy. The Royal Commission into the British nuclear tests in Australia (1984-1985) presided over by Justice James McClelland found that the entire area was hardly unoccupied, and that it was traversed for ‘hunting and gathering, for temporary settlements, for caretakership and spiritual renewal’.

After being identified by the surveyor Len Beadell in 1952, the construction of an airstrip and a village began. The site was rather unimaginatively named Emu Field by the recently knighted Sir William Penney, the mathematician and physicist who led the British nuclear program. Penney—en route to the Montebello Islands off Western Australia to observe the first detonation of a British nuclear weapon—visited the site in 1952, long before the first test was conducted at Emu on 15 October 1953.

As the weapon was loaded and the countdown began, 10-year-old Kunmunara Lester was encamped with his family at Wallatinna, in the now declared Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara (APY) Lands, 170 kilometres north-east of ground zero.

‘The ground shook… boom, boom, boom, boom’ the Yankunytjatjara elder recalled in 2011. ‘That day we seen this quiet smoke, oily and shiny, coming across from the south. We were scared’. [3]

Kunmunara and others encamped at Wallatinna described a mysterious, particulate ‘black mist’ and a sickening metallic smell. Kunmunara and many others testified that people at Wallatinna experienced skin rash, diarrhoea, and vomiting—signs of radiation sickness. Any reasonable person would causatively associate the boom with the mist, and the mist with the sickness, and the sickness with death. After all, this strange mist had never been seen before. The elders at Wallatinna feared it was a bad spirit, or mamu.

These stories of the black mist, and of premature unnatural death, are still emerging from the fog.

HQ-20177S41

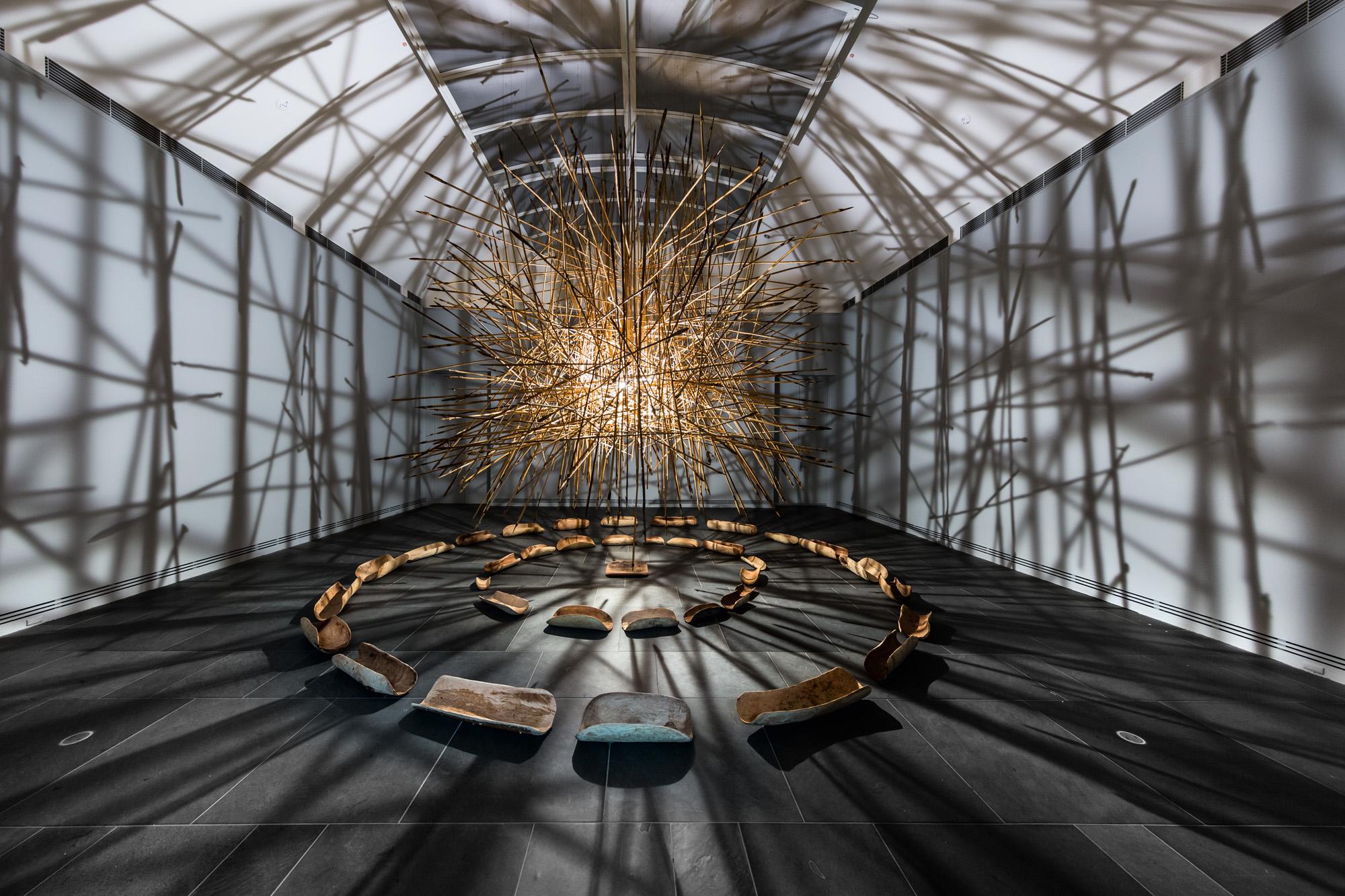

Maureen Douglas, Iluwanti Ken, Freddy Ken, Naomi Kantjuriny, Nyurpaya Kaika Burton, Kunmanara Kaika Burton, Rupert Jack, Adrian Intjalki, Kunmanara (Gordon) Ingkatji, Arnie Frank, Kunmanara (Ronnie) Douglas, Errol Morris, Taylor Wanyima Cooper, Noel Burton, Kunmanara (Hector) Burton, Cisco Burton, Angela Burton, Moses Brady, Freda Brady, Stanley Douglas, Keith Stevens, Yaritji Young, Marcus Young, Kamurin Young, Frank Young, Carol Young, Anwar Young, Mumu Mike Williams, Ginger Wikilyiri, Mr Wangin, Lyndon Tjangala, Graham Kulyuru, Lydon Stevens, Mary Katatjuku Pan, Kevin Morris, Mark Morris, Bernard Tjalkuri, Kunmanara (Tiger) Palpatja, Kunmanara (Willy Muntjantji) Martin, William Tjapaltjarri Sandy, Pitjantjatjara people, South Australia; Kunmanara (Ray) Ken, Kunmanara (Brenton) Ken, Witjiti George, Sammy Dodd, Mick Wikilyiri, Priscilla Singer, Pitjantjatjara/ Yankunytjatjara people, South Australia; Alec Baker, Margaret Ngilan Dodd, Eric Mungi Kunmanara Barney, Peter Mungkuri, David Pearson, Kunmanara (Jimmy) Pompey, Yankunytjatjara people, South Australia; Jimmy Donegan, Ngaanyatjarra people, Western Australia/Pitjantjatjara people, South Australia; Pepai Jangala Carroll, Michael Bruno, Pitjantjatjara people, South Australia/Luritja people, Northern Territory; Roma Young, Ngaanyatjarra people, Western Australia/ Pitjantjatjara people, South Australia; Aaron Riley, Adrian Riley, Walpiri people, Northern Territory; Vincent Namatjira, Western Arrernte people, Northern Territory, Kuḻaṯa Tjuṯa, 2017, Anangu Pitjantjatjara Yankunytjatjara Lands, South Australia, wood, spinifex resin, kangaroo tendon, plus 6 channel DVD with sound, (dimensions variable); Acquisition through Tarnanthi: Festival of Contemporary Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Art supported by BHP 2017. Courtesy APY Art Centre Collective and Art Gallery of South Australia Adelaide.

In 2017 I interviewed three tjamu (grandfathers or senior men) from Indulkana, a community on the APY Lands, to the north-east of Emu. Peter Mungkuri, Alec Baker and the late Kunmunara Pompey had been instrumental in the creation of a major artwork commissioned for the Indigenous contemporary arts festival TARNANTHI at the Art Gallery of South Australia. Hundreds of kulata (spears) had been suspended in a contemporary reimagining of a mushroom cloud, like that produced by the first test at Emu. At the base of the installation, piti (carved wooden bowls) were arranged in two concentric circles. The senior men spoke to me through Anangu translator, Karina Lester, the younger daughter of Kunmanara Lester.

‘He [Peter Mungkuri] was at a place called Victory Well in the Everard Ranges. They went on a camping trip, overnight… and there’s a place—he called it Apatjiwa—which means grinding stone but there’s a big flat rock there. And it was from that location that he saw the mushroom cloud, in the south.’ Then Peter Mungkuri spoke emphatically. ‘Like a fog, like a low fog it travelled. The wind was blowing it but then it was coming back heavy, but low… through the bushes. When that black mist came, eyes became infected, the people were touched by that black mist’.

The softly spoken but forthright Kunmunara Lester was one of the key witnesses to the Royal Commission. His anti-nuclear activism was galvanised by the offhand remarks of a senior official who observed the Emu test, Sir Ernest Titterton, during an interview on ABC Radio in 1980. Titterton announced that the authorities had ‘looked after’ the Anangu downwind of the blast.

Listening in Alice Springs, Kunmunara was incensed. ‘I thought to myself, “he talkin” wrong way, he doesn’t know what happened our end’, he recalled in 2011. [4] He picked up the telephone and spoke to a journalist at the Adelaide Advertiser. A lead story published on 3 May 1980 amplified Kunmunara’s claims that the authorities had not only neglected the Anangu, they had failed to mitigate potential harm from the fallout of the weapons tested at Emu—even as they watched the plume move north-east towards Wallatinna. [5]

Shortly after, Titterton strongly contradicted Kunmunara Lester in an interview with the ABC’s Leigh Gollan broadcast on ABC Radio’s PM program. He described the claims of a black mist as a ‘scare campaign’, emphasising that ‘no such thing can possibly occur… The radioactive cloud is in fact at 30,000 feet, not at ground level. And it’s not black’. [6] In an extraordinary gaslighting, Titterton went on to say that ‘if you investigate black mist… you’re going to get into an area where mystique is the central feature’. At times almost fulminating, Titterton completely dismissed claims that Anangu were exposed to any threat at Emu, categorically denying that any Aboriginal person was harmed in any of the British nuclear tests:

We are quite clear from measurements made by patrols over the whole of the area as to what, if any, hazard remained on the ground… and where there was a hazard… that area was excluded… indeed, the operation leaned over backwards to protect against Aboriginal problems, because of course everybody knows that Aborigines go walkabout. [7]

The Emu tests were not only secretive, but the weapons tested there were highly experimental, according to science journalist Elizabeth Tynan. [8] ‘I think they deliberately chose a place that was a long way away from anyone who could question very closely what they were doing’, she told me in 2016. ‘That’s not a coincidence. I think it’s actually a very deliberate ploy by the British to have a particularly remote site to test weapons that were based on a different nuclear fuel [to that used during the maritime tests in the Montebello Islands]’.

Unlike later tests conducted at Maralinga, there was no Australian safety committee to oversee those at Emu. The British were unhindered. Despite the secrecy, journalists were flown to Emu in airplanes with windows that had been ‘closely curtained’. One of them was the long-serving BBC foreign correspondent, Ivor Jones, who watched the test from an observation post about 20 kilometres away. In his voice report, filed that same day, Jones describes the wraithlike cloud and a surreal delay in the sonic boom:

For a time, it had the familiar mushroom shape, but soon the stalk linking the cloud to the ground grew narrow and descended, like an elephant's trunk reaching down out of the sky. But all this was rather unreal, because too there was no noise of the explosion—that took about 57 seconds to reach us… Then came the din of the explosion, a partial double detonation followed by a low rumbling that seemed to rise and fall in intensity over the desert. [9]

The sound wave also hit another British journalist, Chapman Pincher, a scientific correspondent for the Daily Express. ‘I was shaken by a terrific shock wave’, he wrote, ‘a hot blast that sent a double thunderclap rumbling around the desert for thirty seconds.’ He also describes the sky being lit by a burst of light ‘more brilliant than the sun.’ [10] An unidentified ‘special reporter’ from the Sydney Morning Herald noted something strange immediately after the explosion, in the first two seconds, as the flames shot upwards. ‘Several of the observers noticed the face of an Australian aboriginal [sic] formed by the soaring flames.’ [11]

Peter Mungkuri clearly remembers the aftermath of the test. ‘When we came back from hunting, Mr MacDougall [native patrol officer Walter MacDougall] from Woomera loaded us into the truck back to the homestead, and he continued travelling south towards Emu to monitor the mist…’, he recalled. ‘He [MacDougall] was travelling around, patrolling the region, he was travelling to places like Granite Downs, Indulkana, across to Ernabella, monitoring the fallout, watching the smoke that was coming through’.

Walter MacDougall was appointed native patrol officer for the new weapons testing range at Woomera in 1947, and until 1955 had sole responsibility for conducting surveys and undertaking patrols across the vast prohibited zone. Shortly after, the Pitjantjtatjara–speaking missionary son of a Presbyterian minister had been appointed one of the Protectors of Aborigines in South Australia, presumably for the far northern region. About a month before the first Emu test, MacDougall had visited camps across the Yankunytjatjara lands from Wallatinna to Welbourn Hill to check on the location of the Yankunytjatjara people he had counted during a patrol the previous year.

It was the dingo pup hunting season and Anangu would have been on the move. Dingo scalps were a source of income for the Anangu, with bounties paid for the skins under the terms of South Australia’s Wild Dogs Act. MacDougall noted in his report that the dingo pup hunters travelled further west than previously thought, but that all the Yankunytjatjara counted in 1952 had been accounted for. On the day of the test MacDougall would write to the superintendent the range that ‘there is no fear of Jangkuntjara [sic] natives moving out of pastoral areas, nor is there any possibility of natives based on missions or stations in South Australia moving south of the reserve.’ [12] In his evidence to the Royal Commission, the project security officer from the Commonwealth Department of Supply, C. Morrison stated that

In a vast area like that it would be impossible to guarantee any protection for natives. They could be sitting behind a salt bush and you would never know; even low flying aircraft would not pick them up. So, in that sense, he would be a foolish man to guarantee that he could ensure us that there were no natives in the area… [13]

‘We saw him, we saw Mr MacDougall’, Peter Mungkuri told me in 2017. ‘He’s passed on now, poor old man, but maybe if he was still with us today we could ask him why they did those tests, but maybe he’s got a son and we could ask the question’.

Emu bombs spoiled the country. Kapi (water), kuranu (became bad) [he said this emphatically]. He used the word diduduna which he said meant stirring up the country, making it mucky, making it no good. [14]

Alec Baker said that his countrymen and women threw down their spears and waterbowls as they fled. The kulata and piti are gendered cultural objects. Although laid down after the Emu tests, their making–as an artform–is resurgent in the APY Lands. In describing the significance of these objects and those who made them, Peter Mungkuri used a term which refers to ancestors long since departed, even beyond living memory. ‘Tjamu is saying mirri tjuta—these are people who have been gone a long time … They didn’t have billycans, those days. They used these old tools. That’s part of our tjukurrpa, our ancestral story. This is what we lost, and this younger generation need to learn about it.’

[1] J. R., McClelland, J. Fitch, and W.J. A. Jonas, The Report of the Royal Commission into British Nuclear Tests in Australia : Conclusions and Recommendations . Australian Govt. Pub. Service, vol. 1, 1985, pp. 151-2.

[2] BBC News, 15 October 1953 (broadcast on ABC).

[3] Bush Telegraph, ABC Radio National, 27 September 2011.

[4] Bush Telegraph, ABC Radio National, 27 September 2011.

[5] The Royal Commission concluded that the first test ‘was fired under conditions that… would produce unacceptable levels of fallout’ and that the firing criteria ‘did not take into account the existence of people at Wallatinna and Welbourn Hill down-wind of the test site’. The Report of the Royal Commission into British Nuclear Tests in Australia, vol. 1, p 151.

[6] PM, ABC Radio, 14 May 1980.

[7] PM, ABC Radio, 14 May 1980.

[8] Currently Associate Professor at James Cook University, Elizabeth Tynan’s book Atomic Thunder: The Maralinga Story won the Australian history prize in the 2017 Prime Minister’s Literary Awards.

[9] BBC News, 15 October 1953 (broadcast on ABC).

[10] Sydney Morning Herald, 16 October 1953, p 1.

[11] Sydney Morning Herald, 16 October 1953, p 1..

[12] The Report of the Royal Commission into British Nuclear Tests in Australia, vol. 1, p 172.

[13] The Report of the Royal Commission into British Nuclear Tests in Australia, vol. 1, p 172.

[14] Jack Baker’s evidence to the Royal Commission into British Nuclear Tests in Australia, taken by Maggie Brady at Maralinga Outstation, 19 February 1985.