The Mirror

EditorialAboutA+a Study CentreA+a ArchiveShopClose Menu

At dinner in mid-March this year, I happened to sit next to two retired international airline pilots who spoke enthusiastically about something called ChatGPT that I’d only vaguely heard of. One of them told me he thought it accomplished quite amazing writing tasks.

Since then I’ve heard endless chatter about the language model. Chat Generative Pre-trained Transformer, to give it it’s full name, only arrived in November 2022 but—with one million users within five days of its launch and 100 million by January 2023—it had, up until recently,1 become the fastest-growing consumer application in history. Concurrent with this, on the airwaves and in social media, there’s been a broader, divisive discussion about Artificial Intelligence (AI) in general.

Like video and multimedia artist Tim Gruchy, AI is a baby boomer, having formally entered the world as an academic discipline in 1956 with the Dartmouth Workshop organised by John McCarthy. Although AI’s predecessors, which appear in the writing of Mary Shelley and other fiction, go way back. Frankenstein and his ilk raised some of the same ethical issues now discussed with AI.

Having used various technologies in his art for over 40 years, including AI generators such as DeepDream and GAN, Gruchy is well versed in the rapidly changing arena of AI and art including its pros and cons and broader contexts.

...I began my discussion with Gruchy by asking him what he thought about the current discussion around AI.

My standard answer to such questions is, ‘It's more complicated than that’, and that certainly applies here. As a lifetime (non-exclusive) reader of Sci-Fi and subscriber to the theory that it informs our future, I have long held the opinion that the singularity, to use that word to summarise a dystopic tipping point, was a long way off and has been fuelled in the public’s mind by Hollywood.

What are your thoughts about AI and art right now?

I think the first thing to understand is that there is no common agreement as to what AI is or encompasses. There is a huge and exponentially expanding suite of new AI tools available to artists. All my working life I have strongly pushed the line that it is imperative artists work with new technologies to help all of us understand them better, assimilate them in hopefully more humane ways, and resist or maybe subvert the commercial and industrial-military drivers behind them. And by so doing, hold a mirror to society as art has always done.

Have you used ChatGPT in your art with positive results or in surprising ways?

I have indeed used ChatGPT. I have used mathematical visualisation and artificial life software since the 80s before getting firmly on the AI bandwagon around 2018. When things really escalated last year with DALL-E 2 and then ChatGPT exploding into the wider public consciousness especially in the art world, I made a decision not to use these particular tools for the time being within my practice. This was driven by two thoughts: that it is evolving so rapidly I wanted to pull back and see how things would develop; more pertinently, so much of the imagery in particular had a sameness or ranges of self-similarities, which I was not interested in.

The most satisfying thing I have done with ChatGPT goes like this: artist Panos Couros and I have been making music together on and off for the last year or two and decided we wanted to release an EP, thus demanding a 'band name'. We jumped on ChatGPT and in less than an hour had our name NeuroLounge as well as defining the subgenre and writing a band bio. Fun! Available on SoundCloud now.

The Brothers Gruchy, Tim and Mic grew up in Bundaberg through the sixties and seventies, but it was not until the mid-eighties that they began working together extensively. They pioneered the use of video and multimedia in theatre, opera, contemporary dance and musicals. Tim has moved increasingly into the world of exhibitions and installations, while Mic works mainly in theatre along with editing and producing film and television. Across a broad range of activities they continue to work together and separately, informing each other’s practice in innovative ways.

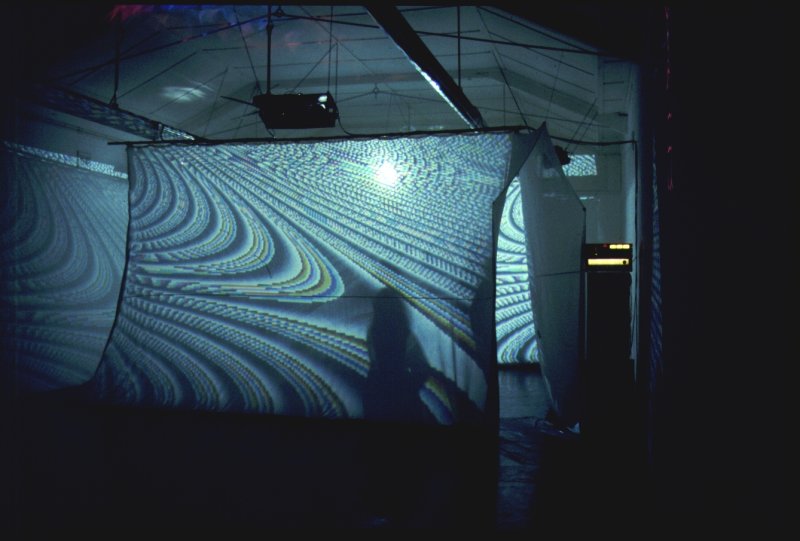

Was your multi-projection installation and soundtrack, Space One, exhibited at the Institute of Modern Art, Brisbane in 1990 something of a precursor for the direction you'd then go in?

It wasn't so much a beginning to this style of work, but a more formal coalescence within the context of an established white space gallery. For some time I had been creating on occasion very large immersive and experiential environments for particular audiences. These were within the more informal contexts of artist parties, the newly emergent dance party scene, nightclubs and other events.

Gruchy’s practice has never been confined the gallery and in fact he consciously aims to work across and against, at times, the boundaries of cultural context.

Of the many multiple image and sound projects you've produced or been involved in over the past few years, which one or two have used AI more extensively or effectively than others? Or perhaps in ways that surprised you?

Beauty/Unbeauty is without a doubt my most effective work using AI to date.

I was commissioned in 2018–19 while working at SAFA (Shanghai Academy of Fine Arts) to co-curate ‘Future Intelligence’, a large international survey show of artists working with AI. Doing extensive research into the area and undertaking conversations with what then was a relatively small number of artists I decided I needed some hands on time.

Picking up on the already dissolved New Aesthetics philosophical movement that came up in 2012 I worked with the DeepDream Generator that uses a CNN (convolutional neural network) to very slowly and painstakingly make this work. It effectively translates the very ideas I was motivated by to the audience, creating just the right balance of attraction and repulsion in many viewers.

New Aesthetics put into question whether AIs will or should share the same aesthetic values as humans. In Beauty/Unbeauty I take the flower as a fundamental representation of beauty. My process then takes two paths, firstly to beauty, secondly to un-beauty. These two sets of AI deep dreaming are then animated and juxtaposed in different ways to explore questions of beauty, showing how human and AI aesthetics are different, yet can also work together.

Entanglement, a work I’m developing now to be shown at Mais Wright in September 2023, has been a wonderful surprise. It takes an unusual approach to machine learning and I have developed a workflow that is not what it was originally intended for and have, over time, carefully crafted a work featuring my niece Michaela Bear that will hopefully surprise and enchant when complete.

In 2019, the same year he co-staged Future Intelligence in Shanghai, Gruchy presented his first Australian solo exhibition Imminence—‘the state or fact of being about to happen’—at Mais Wright Gallery in Sydney.

In mid-2023, Dissolving Worlds at Griffith University Art Museum, featured artworks by the brothers Gruchy focussing on the intersections of technological innovations with biological forms, human perception, AI, and synaesthesia.

* * *

In the recent iteration of the Mission Impossible film series, the mysterious foe, called ‘The Entity’, is a multifaceted AI which has become sentient, knows and senses everything and is aiming for world domination; it must be stopped. Not a new concept but is it far-fetched? Well, no doubt the movie’s makers have done a little homework.

In early 2023, the Center for Humane Technology’s presentation, ‘The AI Dilemma’, began by stating that 50% of AI researchers believed there was a 10% or greater chance that humans will become extinct because of our inability to control AI. The presentation explains how existing AI capabilities already pose dramatic risks to a functional society and how AI companies are caught in a race to deploy quickly without adequate safety measures.

New York based writer Hannah Baer has a different take, less dramatic perhaps but the result may be equally disempowering for society:

AI may take up space in our lives the same way our phones do: by mastering our attention. And if our AI is personified, is it plausible that the AI—as it famously did with New York Times journalist Kevin Roose, when it attempted to derail his marriage—will try to keep our attention by being as histrionic as possible? It’s not out of the question. This banal version (Siri calls you ten times to tell you about a recipe) is one of the more sanguine fantasies. I want to fantasise about AI as utopian, though the most banal fantasies predominate. Will it take our jobs? Will it replace artists and therapists? Of course, only if the technocrats let it.2

Tim Gruchy has a few—more centred perhaps—views of his own about how AI is affecting us and how this may or should go.

Undoubtedly these tools are already being used to benefit humanity in many ways and this can only increase. There is no closing Pandora’s box. These issues affect us all and in fact have been for years. Look at search engines and the money market as two prime examples.

With the rapid emergence of Large Language Models (the specialised AI that’s been trained on vast amounts of text to understand existing content and generate new content) and the tectonic shift implicit in that, combined with Big Tech’s competitive, commercial motivators putting very powerful tools into the general public’s hands with no responsibility or even in-depth analysis of what outcomes may unfold. I am now following the line—being pushed by many scientists working in the field—that we, the world, needs some regulatory oversight.

Medical science examines, dissects, analyses, understands and models the human body and its systems at continuously higher and higher resolutions. At the same time our virtual selves are becoming more and more sophisticated as we increasingly engage with the digital world, through pervasive technologies, hyper-communication and social networks that relentlessly permeate so many aspects of our lives.

At some point in the future there will be a transubstantiation between these realms. Yet what of the soul?

As Gruchy said a little while ago about AI, ‘There is a storm coming’. And now it’s here, you can feel it in the airwaves, hear it around real dinner tables and drink to it in real bars. He says, ‘We must all engage, hopefully in intelligent, considered ways.’

1. Meta’s Threads superseded ChatGPT as the fastest-growing consumer application when it reached ten million active users within the first seven hours of its launch

2. Hannah Baer, ‘Projective Reality’, in Art Forum, Summer, 2023

Author/s: Ian Were & Tim Gruchy

Ian Were & Tim Gruchy. 2023. “Tim Gruchy: AI, Art And Everything.” Art and Australia 58, no.2 https://artandaustralia.com/58_2/p146/ai-art-and-everything

Art + Australia Editor-in-Chief: Su Baker Contact: info@artandaustralia.com Receive news from Art + Australia Art + Australia was established in 1963 by Sam Ure-Smith and in 2015 was donated to the Victorian College of the Arts at the University of Melbourne by then publisher and editor Eleonora Triguboff as a gift of the ARTAND Foundation. Art + Australia acknowledges the generous support of the Dr Harold Schenberg Bequest and the Centre of Visual Art, University of Melbourne. @Copyright 2022 Victorian College of the Arts The views expressed in Art + Australia are those of the contributing authors and not necessarily those of the editors or publisher. Art + Australia respects your privacy. Read our Privacy Statement. Art + Australia acknowledges that we live and work on the unceded lands of the people of the Kulin nations who have been and remain traditional owners of this land for tens of thousands of years, and acknowledge and pay our respects to their Elders past, present, and emerging. Art + Australia ISSN 1837-2422

Publisher: Victorian College of the Arts

University of Melbourne

Editor at Large: Edward Colless

Managing Editor: Jeremy Eaton

Art + Australia Study Centre Editor: Suzie Fraser

Digital Archive Researcher: Chloe Ho

Business adviser: Debra Allanson

Design Editors: Karen Ann Donnachie and Andy Simionato (Design adviser. John Warwicker)

University of Melbourne ALL RIGHTS RESERVED