The Mirror

EditorialAboutA+a Study CentreA+a ArchiveShopClose Menu

Artistic collaboration takes a new form at the National Gallery of Victoria’s (NGV) Melbourne Now in Amalia Lindo’s artwork Telltale: Economies of Time (2022-23). Displayed as a twelve-channel video installation, Lindo has orchestrated a globe-spanning algorithmic experience, calling on over 1,000 anonymous workers from Amazon’s digital crowdsourcing platform ‘Mechanical Turk’ (MTurk).

The MTurk platform gives access to a ‘hybrid machine/human computing arrangement’, a worldwide workforce for diverse technological tasks.1 Each person is a single node, just one neuron in a larger machine, given a fragment of a task (a ‘subtask’) to process. Jeff Bezos calls it ‘artificial artificial intelligence’.2 Workers (or ‘Turkers’) are often given duties that help to train artificial intelligence (AI) algorithms and in doing so, become the organic contacts for AI to comprehend and navigate the intricacies of our world. By churning through images, text analysis and other tasks, MTurk workers create the machine learning databases AI draws on to teach itself.

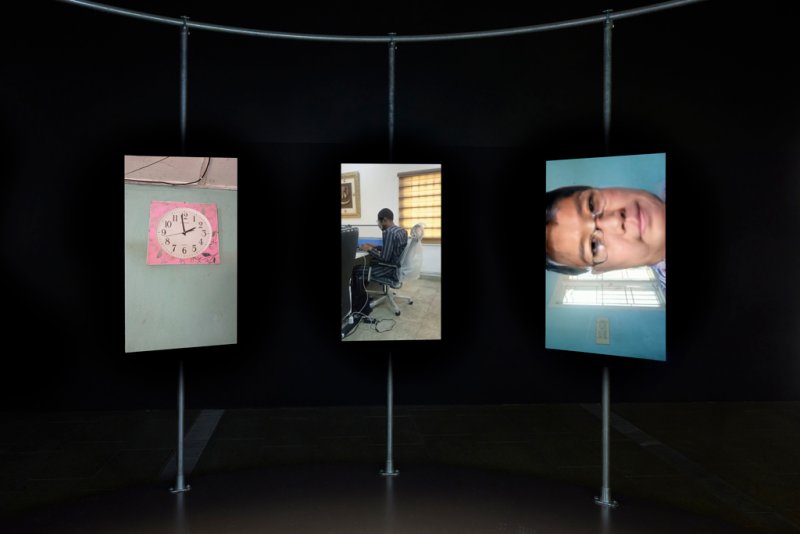

...The name 'Mechanical Turk' refers to an eighteenth-century fake wooden chess-playing "automaton" that hid a human chess player within its base—a hoax maintained on the MTurk platform by hiding the humans that drive machine learning within its digital architecture.3 To create Telltale, Lindo commissioned MTurk workers to submit short videos, each in response to the previous worker's video. These form an ever-unfolding storyline presented across twelve vertically-mounted screens arranged in a three-metre radius ring around a low circular plinth. To sit within this techno-halo is a multi-sensory experience. Images flash and fight for attention across the screens; some draw the eye through boldness (fireworks, a buzz of activity, dizzying motion), while others are engaging in their stillness (ocean views, a lilting flower, slices of serene existence). The associated audio (designed by data scientist Dean Schrieke) envelopes the viewer in a glistening thrum, progressively panning around the ring with subtle effects applied, melding the twelve streams of data into a single, enthralling force.

Before observing the installation, I took 25 micrograms of LSD. Just enough to erode some mental walls and clear the path from brain to mouth. I wanted to take in Telltale from the position of an empty yet eager AI, ready to be trained on the experience of the artwork.

As-unfiltered-as-possible thoughts were recorded over the course of several hours, which were later transcribed for analysis.4 Through these disconnected chunks of observation, broad themes and realisations emerged. I saw Lindo’s installation as a critique of modern work culture, alienation and identity, globalisation, economic inequality, and the downsides of hyperconnectivity.

Telltale opens the lid of MTurk’s eponymous chess trick by providing tiny vignettes into the lives of this globally-distributed workforce—a flurry of domestic environments, workspaces, and the streets people live in. In the captured musings, I frequently returned to words like ‘work’ and ‘job’, but I was also struck by the insight into people’s non-working lives. I got the sense that Lindo’s task gave workers an opportunity to break free from their computers and exist exactly how and where they truly are, rather than as some disembodied unit of productivity like this style of work would typically make them.

I attempted to take in Telltale as an unbiased blank slate, but I failed. I now realise that in the same way Google’s neural network algorithm DeepDream sees eyes and dogs in every unknown pixel, I see what I am trained to see. I could not put aside my programming. I am running an operating system developed over centuries, patched and updated by ongoing community feedback. I am a machine, learning. My mind scrambled to find patterns of familiarity, even constructing elaborate metaphors to pull unrelated stimuli together into a coherent system of meaning. Each video clip was cross-referenced with my internal database of thoughts, experiences and prejudices.

In the videos that make up Telltale, I saw certain states of disrepair, skin tones and scenarios that prompted thoughts of ‘third world economy’, ‘wage slavery’, and ‘oppression’. I thought I saw people living off scraps from the table, lifted out of poverty and into online servitude. The artwork seems to shed light on a modern, hidden working class, kept at a distance by the convenience of the internet. I saw slices of a lifestyle funded by monotonous, repetitive tasks made necessary and relied upon due to crude economic drivers. I judged informal workspaces and low-tech conditions as a sign of suffering. Upon reflection, I do not know that to be the case. It seems that the MTurk platform could provide flexibility and opportunities for earning income from the convenience of a worker’s own home. It could be beneficial for those seeking supplemental income, individuals with limited job prospects, or those who prefer non-traditional employment arrangements. I see now that the platform offers a certain level of autonomy and control.

AI systems trained on prejudiced data can inherit and perpetuate those biases. Similarly, I churned out perceptions and ideas influenced by my upbringing, experiences, and media/cultural biases that I have inadvertently absorbed and replicated. I operate on limited information, incomplete context, stereotypes, personal biases and preconceptions. I risk passing on these frailties. I know that MTurk workers may be forced to work this way by economic necessity, lack of job opportunities, or systemic inequalities, but also that workers voluntarily choose to participate in the platform and have the agency to decide which tasks they want to work on.

What I thought while observing Lindo’s Telltale (and still believe to be true) is that the artwork depicts and contributes to emerging types of labour. It is an algorithmic process, an iterative procedure mimicking the decision-making process of machines, building upon previous inputs. By involving MTurk workers in this way, the artwork highlights the collaborative and social nature of AI development, the economic drivers of algorithms, and hints at their impact on being a human.

The AI that humans create is a mirror of our minds, and the technology is beginning to feed back. With the emergence of OpenAI’s ChatGPT and similar tools, people increasingly turn to technology like a Greek oracle of the everyday. It is no longer unusual to have AI solve life problems by generating timetables, recipes, speeches, homework and a million other menial (or complex) tasks. Teachers are delivering AI-generated lessons, and people are increasingly using ChatGPT and its counterparts to design custom lesson plans tailored for them on any subject imaginable. The trainer becomes the trainee.

So, what does the machine think of a creative project such as Telltale? I fed ChatGPT a description of the artwork, as well as my transcribed (accidental) beat poetry of thoughts recorded in its presence. I asked the AI to reflect on being represented this way.

As an artificial intelligence, I don't possess personal feelings or emotions, so I don't have a subjective experience of being represented in any particular way... Artistic representation and interpretation are subjective and can elicit different reactions from individuals… It is important for viewers, including AI systems like myself, to critically engage with and reflect upon the artwork and the themes it explores.

A fairly muted response typical of this particular AI suite. Maybe with a few more years and a few million more inputs, ChatGPT and other machines will boldly pretend to know what they think, feel and believe—just like we do.

1. U.S. Patent and Trademark Office, Hybrid machine/human computing arrangement, U.S. Patent No. US7197459B1, Google Patents, 2007, https://patents.google.com/patent/US7197459B1/en, accessed 20 July 2023.

2. Pew Research Centre, 1. What is Mechanical Turk, 2016, https://www.pewinternet.org/2016/07/11/what-is-mechanical-turk/, accessed 20 July 2023.

3. Wikipedia, Mechanical Turk, (n.d.), https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mechanical_Turk, accessed 11 July 2023.

4. Tim Hall, Thoughts Prompted in the Presence of Telltale: Economies of Time, 2023, accessed 20 July 2023.

Author/s: Tim Hall

Artist: Amalia Lindo | @amalialindo

Gallery: The Ian Potter Centre: NGV Australia | @ngvmelbourne

Tim Hall. 2023. “Telltale Signs: From Observer To Algorithm .” Art and Australia 58, no.2 https://artandaustralia.com/58_2/p147/telltale-signs

Art + Australia Editor-in-Chief: Su Baker Contact: info@artandaustralia.com Receive news from Art + Australia Art + Australia was established in 1963 by Sam Ure-Smith and in 2015 was donated to the Victorian College of the Arts at the University of Melbourne by then publisher and editor Eleonora Triguboff as a gift of the ARTAND Foundation. Art + Australia acknowledges the generous support of the Dr Harold Schenberg Bequest and the Centre of Visual Art, University of Melbourne. @Copyright 2022 Victorian College of the Arts The views expressed in Art + Australia are those of the contributing authors and not necessarily those of the editors or publisher. Art + Australia respects your privacy. Read our Privacy Statement. Art + Australia acknowledges that we live and work on the unceded lands of the people of the Kulin nations who have been and remain traditional owners of this land for tens of thousands of years, and acknowledge and pay our respects to their Elders past, present, and emerging. Art + Australia ISSN 1837-2422

Publisher: Victorian College of the Arts

University of Melbourne

Editor at Large: Edward Colless

Managing Editor: Jeremy Eaton

Art + Australia Study Centre Editor: Suzie Fraser

Digital Archive Researcher: Chloe Ho

Business adviser: Debra Allanson

Design Editors: Karen Ann Donnachie and Andy Simionato (Design adviser. John Warwicker)

University of Melbourne ALL RIGHTS RESERVED