The Mirror

EditorialAboutA+a Study CentreA+a ArchiveShopClose Menu

A successor to China’s first generation of video practitioners (including Zhang Peili (b. 1957) and Zhu Jia (b. 1963), the multimedia artist Cao Fei (b. 1978) is a key representative of a second generation of video artists born in the 1970s.1 Her creative practice exemplifies a shift from analogue technologies used by Chinese artists throughout the 1990s to new digital and internet-based modes of content creation, introduced in her native Guangzhou, located in southern China’s Pearl River Delta Region (PRD), around the turn of the new millennium.2 Cao has noted that the interplay between the real and the imagined lies at the heart of her practice, conceived not as a binary opposition, but as ‘two trajectories constantly in flux—often indistinguishably close, sometimes intersecting, even parallel’.3 She adds that such a proximity can, in any given moment, ‘give way to distance’.4

Flux located between the real and imagined has always been a part of Cao Fei’s creative oeuvre. Whereas previous generations of artists met video game aesthetics and the internet with skepticism, Cao Fei is one of the first moving image artists from China to fully embrace these technological advancements as creative mediums, as she seamlessly moves between real and virtual spaces. As a result, temporalities in what I identify as ‘concrete flux’, are evoked through the artist’s depictions of urban Guangzhou and its inhabitants throughout the early 2000s. I evoke concrete flux to capture an endless and somewhat contradictory cyclical phenomenon of construction evident within China’s myriad urban environments, particularly prominent in the Pearl River Delta Region.5 This process of construction is followed by an almost immediate obsolescence and destruction. As a result, intense emotional responses emerge from this acute pattern of dislocation, disconnection, and disappearance. Within this temporal, spatial and phycological context of concrete flux, Cao inserts personified elements of the humorous, bizarre, and uncanny found within everyday life into her digital narratives. The resulting temporalities in Cao’s narratives—shaped by concrete flux—stretch, condense, and even contradict local time, history, and memory. In the process they reflect the transformational hybridity, liminality, and multiplicity of Guangzhou’s rapidly changing physical environment.

...As a young child, Cao Fei was certainly no stranger to globalisation within the Pearl River Delta Region, which has often been referred to as an ‘experimental laboratory’.6 Since former Chinese leader Deng Xiaoping first unveiled his 1978 economic reforms, the PRD has become a hotspot for global investment in industrial production along with large-scale urbanisation.7 Far from China’s central government located in Beijing, The Pearl River Delta enjoys somewhat more relaxed socio-political conditions, which support unique geo-specific artistic sensibilities. Its proximity to Hong Kong and long history of exchange with foreign entities coincides with its identity as an intermedial hub for both economic and cultural exchange.

Post-1978 economic growth was followed by rapid expansion of the built environment with high-rise buildings constructed to replace low-level housing. These new patterns of development reflected Deng’s thoughts on reform, in which Special Economic Zones (SEZs) were viewed as ‘a window to technology, management, knowledge and foreign policy’.8 As a result of positive urban economic growth within these SEZs, Deng Xiaoping’s communist party government introduced the market economy as an accepted national economic strategy in 1992. By the end of the decade, Shanghai and Beijing had adopted modes of urban development first introduced in the southern coastal regions, with second and third-tier cities following suit at the turn of the new millennium. The Pearl River Delta’s showcase city of Shenzhen experienced rapid urbanisation that resulted in the coining of the term “Shenzhen speed”, by contemporary art scholar Wang Meiqin.9 This moniker was born in 1984 amidst the construction of Shenzhen’s 160-meter tall International Trade Tower Building. During this period state media reported that workers were able to complete one of the tower’s 53-stories every three days.10 The spirit of ‘Shenzhen speed’ has been replicated within urbanising efforts throughout the PRD and beyond.

Deng’s aforementioned window metaphor was adopted by a Shenzhen-based theme park called Window of the World, which first opened to the public in 1993. The entrance sign of this theme park boasts 您给我一天,我给您一个世界 (nin gei wo yitian, wo gei nin yige shijie).11 Appropriately, Window of the World presents approximately 130 reproductions of world-famous historical landmarks and attractions such as the Eiffel Tower, Mount Fuji, the Taj Mahal, and more. The geographic compression of time and space within only 118 acres can act as a metaphor for the rapid construction and ensuing destabilised temporal experience of Shenzhen and Guangzhou alike. As newly opened ‘windows’, Guangzhou’s rapidly transforming physical spaces gesture towards intermediary simulations of the future—a Utopia with Chinese characteristics. Thus, like the PRD itself, Cao Fei is an intermediary. In her video works she invents future-based notions of time and space, while navigating the in-betweenness and concrete flux of China’s changing cityscapes.

After Cao Fei’s earliest exposure to the international art circuit following her participation in the 2000 exhibition Fuck Off 不合作方式 (buhezuo fangshi), curated by Feng Boyi (b. 1960) and Ai Weiwei (b. 1957), her video projects began to reflect gradual technical refinement, first illustrated by her 2004 project Cosplayers.12 The work debuted at the 2004 Shanghai Biennale, depicting various sites of construction, demolition, and hybridity within Guangzhou. These urban environments are vital to the work’s visual narrative. The term ‘cosplayers’ refers to young people who dress up in flamboyant costume, portraying their favourite anime characters. The cosplayers masquerade in colourful garments, fluorescent wigs, and armour with protruding artificial flames drawn directly from Japanese popular culture, Cao Fei allows these young people to escape into imagined fantasies, within the realities of their multitudinous concrete environments. Unlike earlier videos such as Imbalance 257 (1999), and Chain Reaction (2000), Cosplayers presents more striking contrasts between Chinese subcultures, in this case, cosplay youth culture, and the monotony of the everyday. Cosplayers marks a shift in the artist’s choice of subject matter. Rather than capturing her own generation’s growing pains, she acts as an intermediary for a generation of Chinese youth immersed in a virtual world of video games and costume play from a very young age. Without any way to express their anxieties and feelings of isolation, these individuals resort to an almost utopian escapism, as keenly captured by the artist. Yet, despite their flamboyantly coloured costumes, Cao depicts an inability of the cosplayers to separate themselves from the strange, the bizarre, and the uncanny which characterise Guangzhou’s rapidly expanding built environment.

Early in the video, two young people strike grandiose poses as they prepare for battle. These individuals are situated within a jarringly empty cityscape. This is Guangzhou—literally in the process of urbanisation, as illustrated by the iconic green scaffolding that covers several skyscrapers in the background of the image. An artificial cow and zebra act as hyperbolic representations of contemporary Chinese urban landscapes. Within these urban spaces, unnatural, and even absurd juxtapositions within spaces are commonly found, such as banners proclaiming the glory of China’s socialist economy hanging alongside the iconic golden arches of a McDonalds fast food restaurant, or an advertisement for a new housing development boosting a future utopia against the backdrop of a smoggy urban vista.

Cosplayers explores locations and environments in which notions of urban utopia and dystopia seamlessly merge into one another. The docudrama captures the implications of socio-economic transformations in Chinese youth-culture, exemplified by young people dressed in fantastic costume. The work exemplifies Cao Fei’s ongoing research into the politics of physical and emotional isolation, focused on a generation faced with the pressures of globalisation and an increasingly digitised world. These young people live in a virtual bubble, isolated from others, especially their own family members. They are in search of their own identity, overwhelmed by hyper-realities, macro-consumption, and concrete flux. Cao Fei carefully considers the hybrid-nature of the urban landscapes and costumed figures she depicts. She adds, ‘when you want to express this kind of hybrid complexity, you rely on the use of interactive plays and applications, appropriation, juxtaposition, and assemblage. It’s like the notion of sampling in hip-hop, mixing all kinds of things together’.13 She adds, ‘life is a blur; existence is chaotic’.14 This sentiment is further revealed in the theatrical staging and grandiose posing of characters and situations.15

Cao Fei’s Cosplayers points to a new generations interest in incorporating hybrid forms of global aesthetics and pop culture into their lives. Cao Fei writes, ‘my generation grew up in a situation of hybridity. Many outsiders think that me and my peers were isolated, but hybrid influences have always been there. We were already hybrids. We cannot exactly differentiate what was the original and what was the traditional because there’s nothing that we really belong to’.16 The artist’s sensitivities to hybrid positionalities allow her to identify conditions in which young people live simultaneously in the real and fantastic worlds of Guangzhou and a cosplay universe. She emboldens these ‘real’ characters within her video narrative, inviting them to dress as cosplayers and ‘play’ with others in their native urban environments. The relationship between the cosplayers and their surroundings generates a strong clash between their dreams (imagined spaces) and everyday urban life (physical space). A similar generational dislocation is also marked by how these young people interact with their parents.

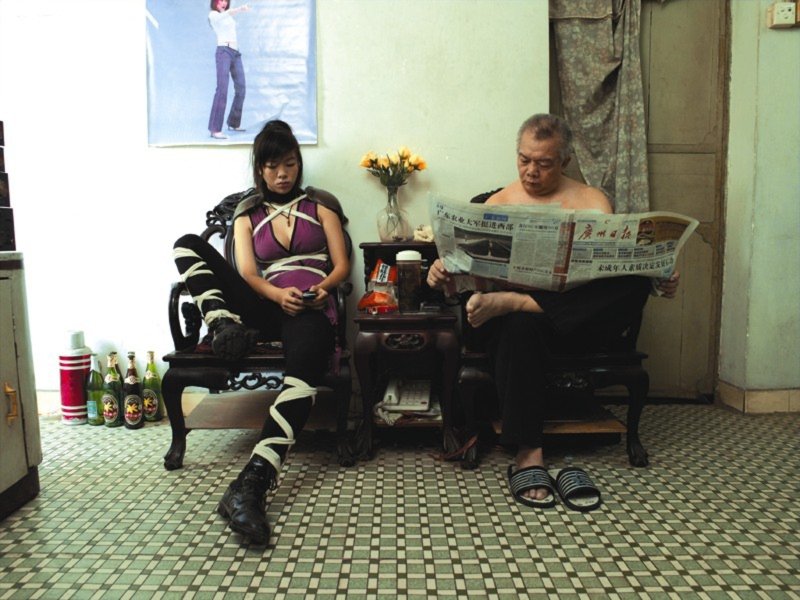

In the second half of the video, cosplayers are depicted at home in costume carrying on everyday activities such as eating, sleeping, or texting. Their activities are counterpoints to the actions of their parents who are watching television, operating a sewing machine, reading the newspaper, or cooking dinner. While these individuals share space with each other, they are simultaneously out of time with one another in both emotion and action. While their parents (largely) occupy domestic everyday spaces rooted in reality, these young cosplayers embody virtual animated or game time, through dress as well as actions such as cleaning one’s dagger or preparing for battle. Thus, it would be incorrect to assert that Cao Fei’s early works are solely documents of urban change. Rather, they are responses to individual and collective psychological conditions and concrete flux at the helm of China’s economic and environmental transformation over the past three decades.17

Cao embraces the accelerated time of the built environment, revealing fluidities and virtual liminalities intrinsically tied to socio-economic conditions found within the Pearl River Delta, named the world’s factory during the early 2000s.18 She prioritises temporalities in tension, observing urban and cultural spaces in transition. In Cosplayers, present time is thickened by new intersecting time zones located between the rural and the urban, the real and the virtual, the so-called traditional and the contemporary, the past and the future.19 Cosplayers move both in and out of time and space with their parents, their city, and even each other.

Cao Fei does not simply document rapid social change, or the immersion of real and virtual space, but rather the psychological impact resulting temporalities have inflicted on themselves and others. She is situated within contemporary urban temporalities of concrete flux. The philosopher Henri Lefebvre (1901-1991) wrote, ‘With the advent of modernity time has vanished from social space. It is recorded solely on measuring-instruments, on clocks, that are isolated and functionally specialised as this time itself. Lived time loses its form and its social interest’.20 Within the current contemporary context, no more is this more apparent than in China where Cao’s artistic practice embodies the impulse to preserve sensitivities towards lived time vs. measured time, despite living in a society where techno-urban progress increasingly favours the urge to forget.

1. In 1988, Zhang Peili (b. 1957) created 30x30, widely regarded as the earliest example of Chinese video art. Video art practices were subsequently established by many of Zhang’s younger peers based in Hangzhou. Artists include Qiu Zhijie (b. 1969), Wu Meichun (b. 1969), Yan Lei (b. 1965), Tong Biao (b. 1970) and others. Throughout the 1990s, artists based in Beijing, Shanghai, Chongqing, and elsewhere began experimenting with video. Many of these moving image projects sought to both document the passage of time, in addition to making viewers more mindful of time’s existence, along with its creative and controlling properties, and aesthetic qualities. Cao Fei (b. 1978), Chen Qiulin (b. 1975), Yang Fudong (b. 1971), and other artists born throughout the 1970s mark a generational shift in terms of their interests in stronger forms of narration and allegory. See: Ellen Larson, ‘On Time: Video Art from China’, PhD Dissertation, University of Pittsburgh, 2022.

2. In his book Digital Media in Urban China: Locating Guangzhou, Wilfred Yang Wang argues that Guangzhou boasts the nation’s highest ‘socio-informational index’, an official measure of the process of social integration of digital technologies in China, which first emerged in the 1990s. He adds, “The rapid development of information and communication technologies (ICTs) in recent years have diversified Guangzhou’s manufacturing and processing industries. In terms of new ICT consumption, Guangzhou’s 66.92 million internet users rank highest in China, and its 66 per cent internet penetration rate is also the highest in the provinces”. See Wilfred Yang, Digital Media in Urban China: Locating Guangzhou, Rowman and Littlefield: London, New York, 1991, p. 29.

3. Klaus Biesenbach, ed., ‘Cao Fei in conversation with Klaus Biesenbach,’ Kaleidoscope Asia 3 Spring/summer 2016, pp. 138-143.

4. Ibid.

5. Early works by artists living in Guangzhou, such as Lin Yilin (b. 1964), along with Chen Shaoxiong (1962-2016), Xu Tan 徐坦 (b. 1957), and Liang Juhui (1959-2006), all members of the Big Tail Elephant Group大卫像工作小组 (Daweixiang gongzuo xiaozu), document the concrete flux of rapid urbanism, economic expansionism, globalizing conditions, and acute anxieties on individual and collective experiences and subjectivities.

6. Hou Hanru, ‘Beyond: An Extraordinary Space of Experimentation for Modernization’, The Second Guangzhou Triennial, BEYOND: an extraordinary space of experimentation for modernization, Guangzhou: Lingnan Art Press, 2005, p. 21.

7. See: Jonathan Spence, The Search for Modern China, New York, London: W. W. Norton & Company, 1991, pp. 652-682.

8. During the past four decades, globalizing urbanization within the Pearl River Delta has grown exponentially. Since 1978, a select number of southern Chinese cities, labeled as Special Economic Zones (SEZs), attracted wide sweeping development and foreign investment due to their newly flexible economic policies. Between 1978 and 1984, China established SEZs in Shantou, Shenzhen, Zhuhai, and Xiamen, along with the entire island province of Hainan. In 1984, Guangzhou, along with thirteen other coastal cities were opened to international investment.

9. Wang Meiqin, Urbanization and Contemporary Chinese Art, New York: Routledge, 2016, p. 78.

10. Ibid.

11. This phrase translates to ‘Give me a day, I’ll give you the world’.

12. The 2000 multimedia exhibition Fuck Off (不合作方),co-organized by Ai Weiwei and Feng Boyi, was staged at the Eastlink Gallery, an abandoned warehouse located on Shanghai’s Suzhou River Road. The exhibition took place at the same time as the 2000 Shanghai Biennale, curated by Hou Hanru, and was intended to challenge the Biennale’s alignment with official art circles. In a publication created in conjunction with the exhibition, Cao Fei writes that “imbalance is a contemporary experience, an uncommon experience that is shared among college students in China. It restricts us and changes us, but at the same time it enables us to expand and be flexible… It is on the edge of human relationships and in between pleasure and despair.” Ai Weiwei and Feng Boyi, eds. Fuck Off (不合作方式), Shanghai: EastLink Gallery, 2000, p. 16.

13. Cao Fei, I Watch That Worlds Pass By, Cologne, Snoek Verlagsgesellschaft, 2015, p. 243.

14. Ibid.

15. Cao Fei’s inspiration for Cosplayers comes from the rupture between globalisation efforts that have dramatically altered China’s economic landscape and the country’s socio-economic conditions. Originally imported from Japan, cosplayer characters are not indigenously Chinese, yet these images from Japanese popular culture have not only made a profound impression on the artist’s life and artistic practice, but also on the lives of the post-1980 generation growing up in China. These cosplayers have become ‘naturalised’ in China, reformed and modified to meet the needs of a Chinese audience and particular social conditions.

16. Cao Fei, I Watch That Worlds Pass By, p. 243.

17. China has experienced unprecedented economic development and cultural change since Deng Xiaoping first unveiled a series of reforms in 1978.

18. In the last few decades, tens of millions of migrant workers from China’s inland provinces have flocked to the Pearl River Delta in search of work in the estimated 60,000 factories located throughout Guangdong Province. These factories, making up the world’s largest industrial region, manufacture products such as smartphones and other electronics, household items, furniture, and clothing, which is exported to most parts of the world.

19. Christine Ross discusses the ‘thickened present’ in her book The Past is Present, It’s the Future Too, New York, Bloomsbury, 2012. Ross writes, ‘the temporal is a turn in which the past, present, and future persist sufficiently to allow for forms of realignments. It is a turn constitutive of a regime of historicity in which the temporal category of the present is thickened by its proximity to the past and to the future’. Terry Smith offers a rich analysis of Ross’s theorization in his book Art to Come: histories of contemporary art, Durham: Duke University Press, 2019. I owe much gratitude to Professor Smith for introducing this text to me in a 2017 University of Pittsburgh graduate seminar.

20. Henri Lefebvre, The Production of Space, Hoboken, Wiley-Blackwell, 1992, p. 95.

Author/s: Ellen Larson

Ellen Larson. “The Concrete Flux Of Cao Fei's 'Cosplayers'.” Art and Australia.com https://artandaustralia.com/A__A/p157/the-concrete-flux-of-cao-feis-cosplayers

Art + Australia Editor-in-Chief: Su Baker Contact: info@artandaustralia.com Receive news from Art + Australia Art + Australia was established in 1963 by Sam Ure-Smith and in 2015 was donated to the Victorian College of the Arts at the University of Melbourne by then publisher and editor Eleonora Triguboff as a gift of the ARTAND Foundation. Art + Australia acknowledges the generous support of the Dr Harold Schenberg Bequest and the Centre of Visual Art, University of Melbourne. @Copyright 2022 Victorian College of the Arts The views expressed in Art + Australia are those of the contributing authors and not necessarily those of the editors or publisher. Art + Australia respects your privacy. Read our Privacy Statement. Art + Australia acknowledges that we live and work on the unceded lands of the people of the Kulin nations who have been and remain traditional owners of this land for tens of thousands of years, and acknowledge and pay our respects to their Elders past, present, and emerging. Art + Australia ISSN 1837-2422

Publisher: Victorian College of the Arts

University of Melbourne

Editor at Large: Edward Colless

Managing Editor: Jeremy Eaton

Art + Australia Study Centre Editor: Suzie Fraser

Digital Archive Researcher: Chloe Ho

Business adviser: Debra Allanson

Design Editors: Karen Ann Donnachie and Andy Simionato (Design adviser. John Warwicker)

University of Melbourne ALL RIGHTS RESERVED