The Mirror

EditorialAboutA+a Study CentreA+a ArchiveShopClose Menu

“…we moving it is quiet now the dusk is the same as dawn over india red soil i flew above the alps they were below me sharp peaks model mountains the train goes into a tunnel it is dark and dark i'm scared it was hot my feet got too big for my shoes…”

Ania Walwicz, travelling (1996)

This paper forms part of a broader project looking at experimentalism in the Australian arts and media during the 20th century. My aim here is quite simple: I am asking after ‘experimentalism’ to see how or why it should be understood or disentangled from ‘avant-gardism’ in the work of Australian artist filmmakers post-WWII. Defined by Benjamin Piekut as a “historically specific network” and further one that “does not express a radical political imagination”, experimentalism is understood as more closely engaged with “science-and-technology discourses” and rather than an avant-garde, instead forms a “rearguard” practice—noted as early as 1964 by Italian theorist and television executive Angelo Guglielmi (Piekut, 2019, 2). How can mapping this specific network provide a vector for the histories of the expanded arts after WWII in Australia, and in particular in the work of the Cantrills, who’s practice emerges from the anarcho-technocratic poetics of Harry Hooton (1908-1961) in Sydney in the 1950s (see Fielke, 2020)? Given it dates the first international “experimental” film festival at Knokke-le-Zoute—Cannes Film Festival began in 1946, and Belgium’s ‘world film and fine arts festival’ was held in 1947—1949 seems like a good place to start.

Here is how Corinne Cantrill remembers attending the third iteration of the festival in 2014:

In 1967/68 (Dec./Jan.) we attended the Knokke Experimental Film Competition in Belgium, organized by the great, late Jacques Ledoux he died in 1988. People came from across the world to be there - there was a Gregory Markopoulos Retrospective, the premiere of Michael Snow's ‘Wavelength’, with separate sound on a powerful sound-generating device, lots of films from USA - Robert Nelson, Gunvor Nelson, Will Hindle, Paul Sharits; really powerful films from Germany and Austria, from Japan, and from England - Stephen Dwoskin, Malcolm Le Grice, Don Levy, Yoko Ono (whose events and performances we knew already from London) - so it was very full on, and a turning point in our filmmaking lives.

We had been wavering about making films, or animated films, but after Knokke we knew we wanted to work in this more experimental area. (Pinguim, 2014)

Slide 2 EXPRMTL 4 began on Christmas Day 1967 and continued into the New Year (from 25th to the 2nd) at a Casino in the Belgian municipality now named Knokke-Heist. It was officially titled the known as Le festival international du cinéma experimental de Knokke-le-Zout and was created by Jacques Ledoux, who was the curator of the Belgian Royal Cinematheque. It ran for five editions over 25 years, ending in 1974 (’49, ’58, ’63 are the first three, ’74 is the fifth and last iteration of the festival).i

Corinne Cantrill was born in Sydney in 1928, so was 39 at the time. Arthur Cantrill was also born in Sydney, in 1938. They were married in 1960. Recent international interest in the Cantrills films, particularly in Berlin at the Arsenal and in Spain demands that our local histories and its political aesthetics be attendant to the ways in which their work is currently being reconsidered by contemporary art and film institutions. Given so much of their work is concerned with the settler-colonial presence in the Australian landscape, it comes into direct confrontation with First Nations iconography and locations sacred to Aboriginal Australia (Uluru being only the most obvious). Significant figures like the former artistic director of the Melbourne International Film Festival (MIFF), Michelle Carey, is currently championing their work in Europe and the US (an upcoming screening of Corinne Cantrill’s personal film-manifesto In This Life’s Body (1984) will be held at the Museum of the Moving Image in New York later this month).

xxx

Slide 3 On the 6th of October 1995 two landscape films by Australian filmmakers Arthur and Corinne Cantrill were shown at the Louvre. While both films were deeply involved in the abstract quality of the film medium—a treatise on three-colour separation written in the 1970s was their specific contribution to the catalogue for the exhibition—the Australian landscape, captured by the settler-colonial gaze and projected for a European audience, provided the contents for the Cantrills’ experiments: Heat Shimmer (1978) and Waterfall (1984). For three decades, their commitment to experimentation through filmmaking had followed their experiences in Belgium.

While the question of how to capture the landscape has been a constant concern for the vast majority of the Cantrill’s films, another question was what these films set in Australia could show to an audience of mostly European modernists. Slide 4 In 2019, nearly three decades after the screening at the Louvre, the Cantrills films would again be presented to contemporary European audiences, this time at the Arsenal in Berlin, where their films, including The Second Journey to Uluru (1981) was remastered and digitised, and shown—coincidentally—in the wake of the Uluru Statement from the Heart, the Makarrata or treaty process agreed to and set out by First Nations delegates in 2017, whereby it was derailed and ultimately sidelined by the recently ousted Malcolm Turnbull and the accidental Morrison Government. In Berlin for the screenings, the artist Yhonnie Scarce, a Kokatha and Nukunu woman was compelled to leave the room when the remastered and digitised images of Uluru’s interior cave systems and peripheries were projected into the large underground space, a former crematorium, now known as the Silent Green Kulturquartier..

As the Australian landscape is a necessary focus for any settler colonial aesthetics, so landscape becomes a key consideration for any history of Australian filmmaking. Yet to critically engage with these films, which are yet to receive close examination and analysis for their experimentalism in artist filmmaking in Australia in the mid-20th century, the obvious entry-point into this vast and diverse project is the Cantrills Filmnotes, a long-running journal of film and experimental media edited by Arthur and Corinne themselves, between 1971 and 2000. Slide 5 As Dirk de Bruyn has noted more recently, the Filmnotes became a mouthpiece for the filmmakers, operating at least in part “as a machine for the transformation of dissent into cultural capital.” (De Bruyn, 2014).

Another reason an Australian national focus is needed here, to be held in contrast with a transnational or formal histories of filmmaking in the period, is the unique funding “environment” that was supported not by the national film body, Film Australia, but through the recently established Australia Council for the Arts' Experimental Film Fund in 1970 (later the Experimental Film and Television Fund), as the Filmnotes initially were. Furthermore, the palpable anxiety of the settler colonial gaze over the Australian landscape, and during a period of intense debate over the sovereignty of British settlement, followed in the wake of Indigenous Australian suffrage, beginning in 1962 and then nationally: “in 1967 we were counted, in 2017 we seek to be heard” says the Statement from the Heart—as well as the beginnings of native title recognition over the lands and waters of this vast continent (the Milirrpum, or Gove land rights case, in which the judgement ruled against Yolngu claimants in favour of British colonial law, was heard in 1971).

This settler history may have been aptly crystalised in the writing of Gerald Murnane The Plains, 1982?:

I looked around me for some detail of a painted landscape on the wall or some gesture made by a porcelain figure in the crystal-cabinet or some pattern in the threads of an anti-macassar that seemed the nearest sign of the other world. (Gerald Murnane, Landscape with Landscape, 1985)

xxx

Since the arrival of the so-called First Fleet of British settlers to Australia, images of the Australian landscape have operated by representing an oscillation between its documentation, and what Chiara Bottici calls the “European imaginary”, in the sense of its mythmaking and aesthetic identitarianism. My question is whether it is now possible to see in the moment of 1967, a different kind of imaginary emerging – the imaginary of a “Australian” vision for the South Pacific: not a vision of reality subjected to the service of science, but an experimental aesthetics subjected to the politics of avant-gardism. (cf. Smith, 1960)

Slide 6 I’ll explain briefly what I mean. If we jump in time again, to the first ConFest, then known as Down To Earth festival, and held on the banks of the Cotter River in the ACT over a few days from the 10-14th of December 1976, the invitation to the event came from Jim Cairns, formerly a minister in the Whitlam Government and the recently deposed Treasurer of Australia (who had also been the leader of the Vietnam Moratorium Campaign in Melbourne, 1970). Might this document suggest the course upon which the EXPRMTL festival intervenes in the development of Australia’s festival and arts cultures in the post-war era? Slide 7 Like, for example, how films such as Michael Lee’s Turnaround (1983), documents these festivals (in contrast to the urban parades of Moomba) in the late 1970s and early 80s. Lee was a close collaborator and acolyte of the Cantrills—he had been the driver for the Cantrills ‘Second Journey to Uluru in the late 1970s. (The film was debuted at MIFF in June, 1981). Here’s Cairns:

The purpose of the festival is to show the urgent need to SHAPE ALTERNATIVES NOW.

Ways must be found because of the violent, acquisitive, alienated, industrial society which now poses a threat to survival. People have for centuries searched for equality and the right and ability to determine their own development. Individuals must accept responsibility for themselves. Personal happiness and equality, as much as a good society, depend upon self realisation. The most vital factor today is a sense of true identity. This is lost because our identities are created by others - not by ourselves. The all-powerful externally created hegemony in this assumed-to-be-free society, and its internalised personal alienation, must be understood if self realisation can be achieved.

The starting point must be the "will to be the self which one truly is".

There must be equality and effective individual participation in government and in every other group activity if self realisation is to be achieved.

The festival will be concerned with the search for the true nature of man and woman.

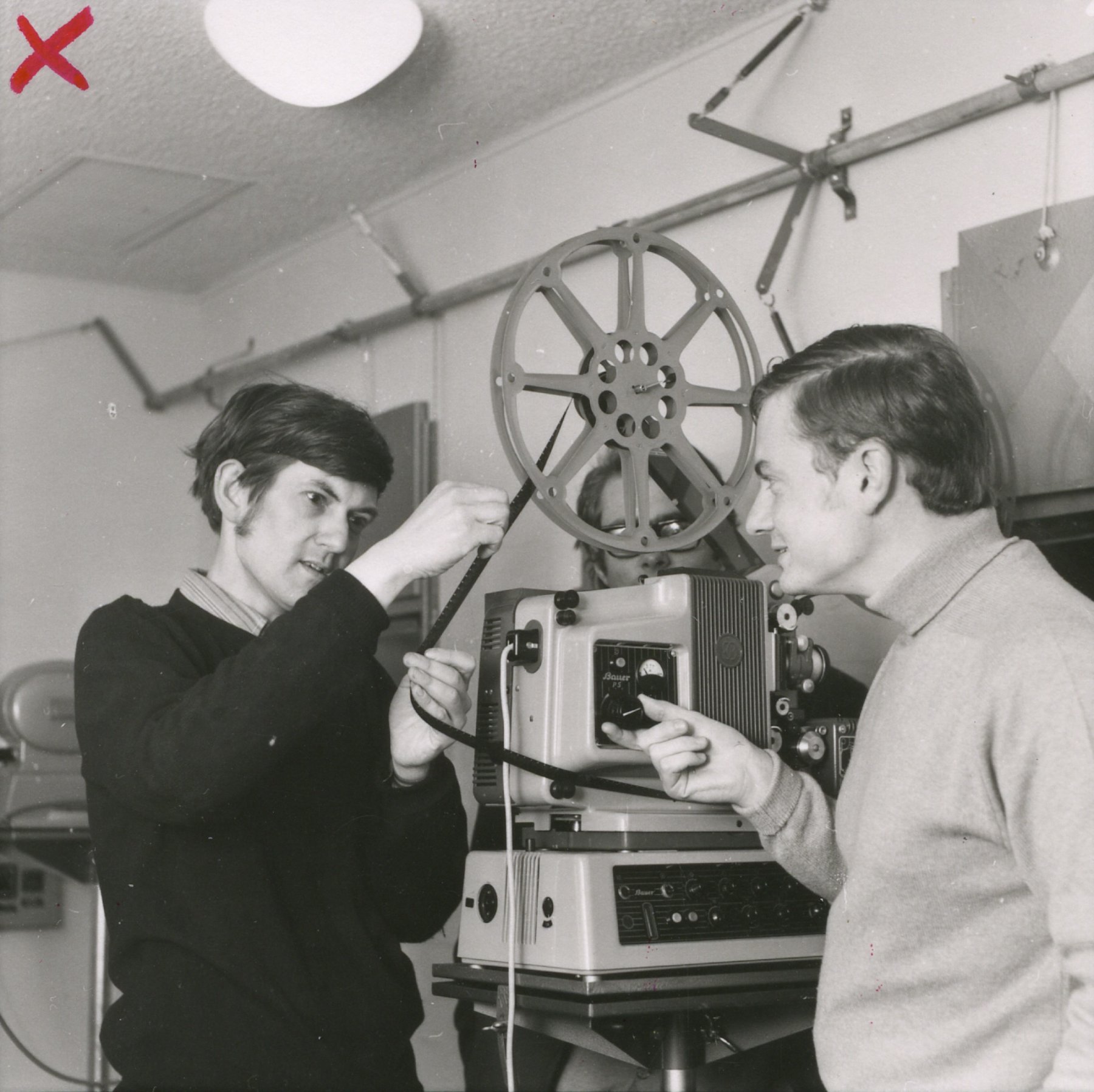

Slide 8 While this paper continues work I have been undertaking on experimental and avant-garde filmmaking, artist-film or so-called “independent” films from filmmaker employees of the ABC, to the Filmmakers’ Co-ops and artist communities in Australia and across the Pacific. Beginning with their film Mud (1964) and continuing onwards I am trying to establish the role played by the Cantrills as pivotal figures for the expanded arts of Melbourne and Australia from the 1970s and on to their recognition for the Queen’s 85th birthday honors in 2011, bestowing the Cantrills with an OBE:

For service to the visual arts as a documentary and experimental film makers, and to education in the creative arts field, particularly surrealism and avant-garde cinema.

In many senses this recognition is both incongruous and somewhat (necessarily) reductive, considering the staggering amount of work the Cantrills have produced (they continued to “work” right up until 2020, hosting regular screenings and didactic events in their Castlemaine home). This entanglement of their work with the state deserves closer inspection and criticism than it has garnered so-far. Since the publication of the Cantrills Filmnotes in 1971 the presence of Arthur and Corinne, along with their sons Ivor and Aaron, in the media arts landscape has been immeasurable and perhaps because of this somewhat invisible.

xxx

The question of what this invisibility might look like was, had already been tentatively formulated in 1966 by Fluxus artist and publisher of the Something Else Press, Dick Higgins. For Higgins, it was the concept of intermedia that provided a model for the arts after WWII, to coalesce around an idea or a mood that was, by the end of a decade marked by seismic technological and cultural shifts. Higgins went so far as to call it an ‘uncharted land’. (Higgins, 1966). ‘Expanded Arts’ was another term that came to be used to describe the promiscuity of practices helping to produce new horizons for the arts of the 1960s and 70s. But it is this term—intermedia—which pops up again in Chris Hemensley’s discussion with Corinne Cantrill on 3RRR radio in 1983. Significantly, Hemensley’s suggestion of a ‘New Australian Poetry’, in 1970 had sought to internationalise the potential of what he saw as the ‘little mags’, even as he left for England (Meanjin, 29, 120). His parting shot: ‘In Australia there is a battle with anti-Anti-Intellectualism before one even arrives at the stage of anti-intellectualism i.e. the Academy’ (Ibid). The answer, he believed, was in the ‘open communications’ that contemporary technologies were only just making possible at the time (Ibid. 121).

Slide 9 The radicalism the Cantrills had encountered in Belgium, 1967, was led in part, by none other than Harun Farocki, Holger Meins, Gerd Conradt, and Oiml Mai who were protesting the festivals emphasis on experimentalism and its apparent lack of political commitment. Meins (later of the RAF and dying on a hunger strike in prison in 1974), would make a film with Farocki titled “How to make a molotov cocktail” precipitating the events that would see Cannes cancelled in 1968 and the student protests that took over much of Germany and France. As Xavier Bardon writes in 2013: ‘The strength of EXPRMNTL lay in the articulation of its three parts… These are, according to Ledoux in 1974: first, the film competition, second the non-film related activities, third the unexpected. The first and the second lead to the third.’ (Bardon, 2013) EXPRMTL 4 Jury member and artist-filmmaker, Shirley Clarke (from New York), stated in an interview undertaken soon after the events: ‘I think Rome is burning. Which is always a good time to let oneself go. … A new world is coming. The end of this world is coming, but a new world will take its place.’

In the 1970s the Cantrills’ encounter with the arts-collective Bush Video, and multi-media artist Joseph el Khourey, as well as their turn to pre-colonial and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultures through the anthropology of Baldwin Spencer, meant a turn away from the doctrinaire avant-gardism of their earlier work. Spencer’s films from 1900/1901 provided an archival model for making work that was no longer about novelty. El Khourey had suggested these films to them, and their encounter with idiosyncratic cultural historians like Harry Smith during their time in the US (between 1973-75) had alerted them to the broader context in which their work was situated. Andrew Pike, whom Arthur Cantrill had first worked with at ANU in 1969, described the work of Japanese artist Terayama Shuji as an example of the ‘intermedial creative practice’ in the context of a ‘Pacific community of poetry’ made explicit for the Cantrills in the mid-1970s (Pike cited in ‘Little History,’ 413-4). Things began to shift away from Harry Hooton’s technocratic vision of the future, to less concrete visions of an expanded cultural practice. But can the experimentalism of EXPRMTL indicate another side to this political turn? Today it seems as though it is impossible to distinguish the experiment from its political implications.

[i] As Louise Curham notes in her 2004 MFA thesis: “The Filmnotes indicate that the Cantrills attended several of the Knokke-Le-Zoute experimental film festivals, where a number of expanded cinema works were shown so they had first hand experience of the European style of the work. [The Knokke film festivals were held in the casino in the Belgian town of Knokke-Le-Zoute (renamed Knokke-Heist by 1973). The festival is referred to by a number of different names. Cantrill’s Filmnotes No.14/15, Aug 1973, p 44 list the years of the festival as 1949, 1958, 1963, 1967/8. This issue of the Filmnotes indicates that another would be held from 25 Dec 1974-2 Jan 1975.Amongst the names the festival was known by are Exprmntl 4, the 4th International Experimental Film Competition (Dec 26-31 1967) [source: P Mudie,Ubu Film Sydney Underground Movies 1965-1970; University of New South Wales Press, 1997, pp 86-7]. Exprmntl 5, Knokke-Le-Zoute International Experimental Film Festival [source: Cantrill’s Filmnotes No 16, Dec 1973, p 31].

Author/s: Giles Fielke

Giles Fielke. “EXPRMNTL Filmnotes: The Cantrills In Belgium, 1967.” Art and Australia.com https://artandaustralia.com/A__A/p192/exprmntl-filmnotes-the-cantrills-in-belgium-1967

Art + Australia Editor-in-Chief: Su Baker Contact: info@artandaustralia.com Receive news from Art + Australia Art + Australia was established in 1963 by Sam Ure-Smith and in 2015 was donated to the Victorian College of the Arts at the University of Melbourne by then publisher and editor Eleonora Triguboff as a gift of the ARTAND Foundation. Art + Australia acknowledges the generous support of the Dr Harold Schenberg Bequest and the Centre of Visual Art, University of Melbourne. @Copyright 2022 Victorian College of the Arts The views expressed in Art + Australia are those of the contributing authors and not necessarily those of the editors or publisher. Art + Australia respects your privacy. Read our Privacy Statement. Art + Australia acknowledges that we live and work on the unceded lands of the people of the Kulin nations who have been and remain traditional owners of this land for tens of thousands of years, and acknowledge and pay our respects to their Elders past, present, and emerging. Art + Australia ISSN 1837-2422

Publisher: Victorian College of the Arts

University of Melbourne

Editor at Large: Edward Colless

Managing Editor: Jeremy Eaton

Art + Australia Study Centre Editor: Suzie Fraser

Digital Archive Researcher: Chloe Ho

Business adviser: Debra Allanson

Design Editors: Karen Ann Donnachie and Andy Simionato (Design adviser. John Warwicker)

University of Melbourne ALL RIGHTS RESERVED