The Mirror

EditorialAboutA+a Study CentreA+a ArchiveShopClose Menu

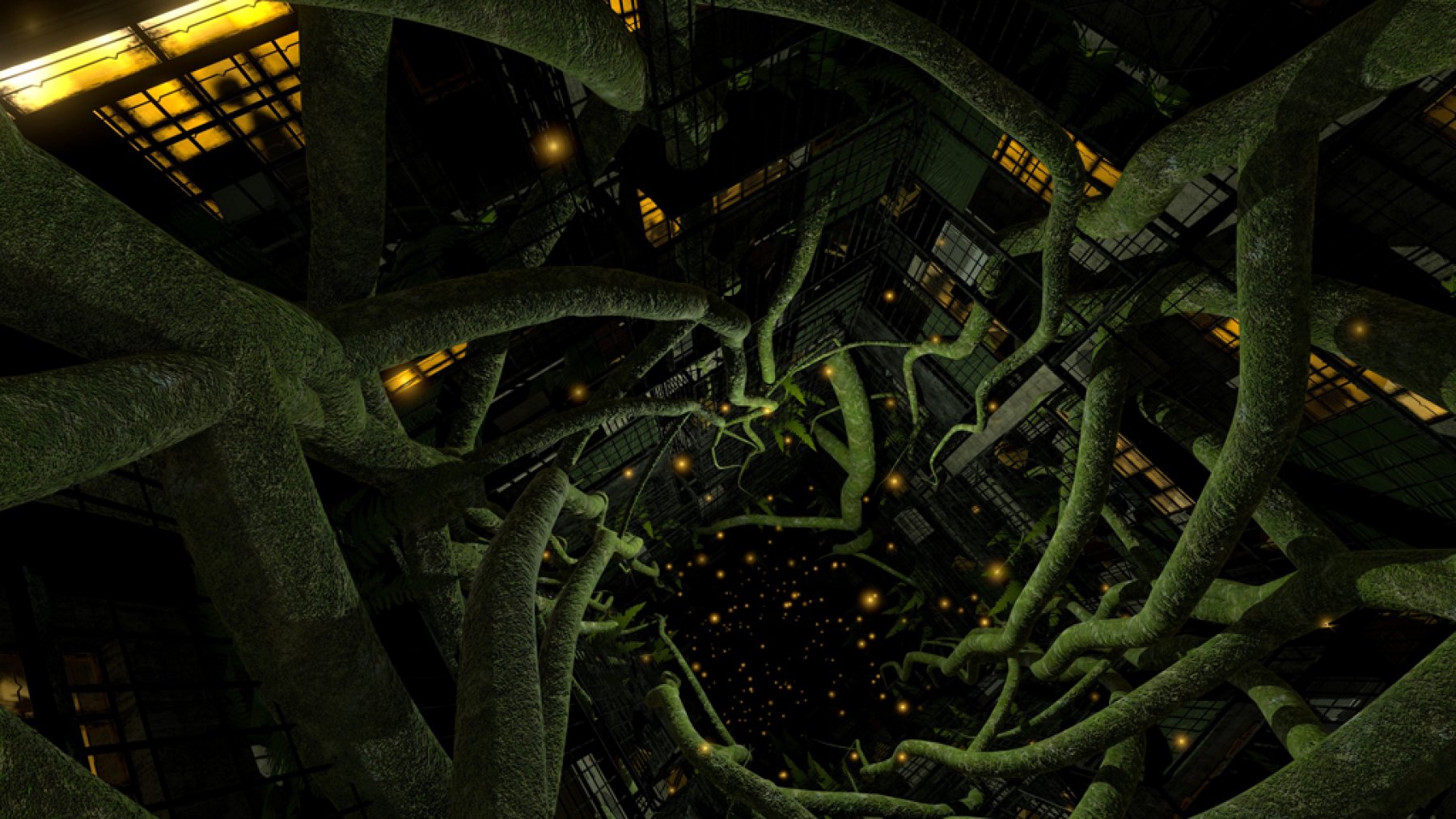

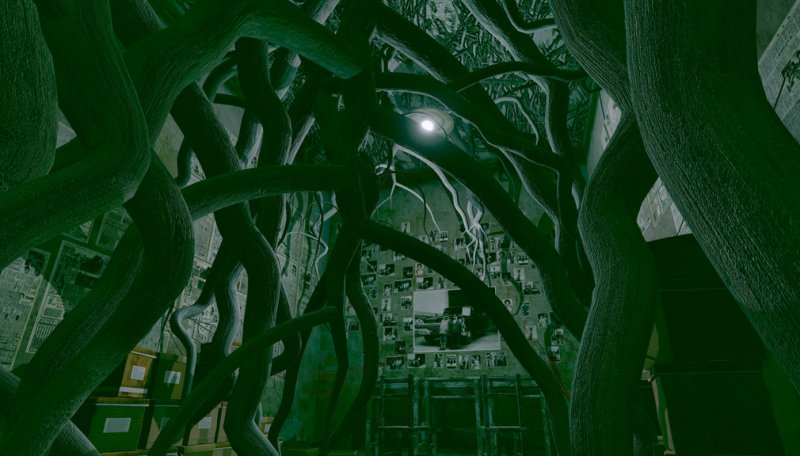

We wake up facing a body. He lies under a blanket of newspapers on a concrete bed in an overgrown prison cell teeming with ferns, tree roots and floating insects. He clutches a photograph of a young boy in one hand, with an intravenous drip feeding into his left arm. As we pull away, we float and realise that we are untethered from the ground. Now flying through the cell, we can see the massive scale of the room around us: its looming iron bars, the depth of the toilet in one corner, large newspapers instructing me to ‘Follow the great leader and march forward courageously’. It becomes apparent we inhabit the body of an insect floating freely through space in the presence of a dying man. We search the room, seeking among the tangled plants and document fragments a clue to this body’s identity but find only a swirling cloud of insects silently flying above us at the roof of the cell. Exhausted, we sink towards the floor and pass through it, its thin digital surface disappearing beneath us as we plunge into the infinite depth of an underground prison choked by tree roots, floating down surrounded by fireflies as the man’s body slowly disappears above us.

This opening sequence in Hsin-Chien Huang’s virtual reality work Bodyless (2019) plays on a tangle of uncertainties. The body’s identity is unexplained, newspapers spread throughout the room with headlines declaring “BOUNDLESSLY LOYAL TO THE GREAT CHAIRMAN” and “LONG LIVE THE GREAT CHAIR CHAIRMAN” situating us within the Taiwanese ‘White Terror’ (1947-1987), a period of state-sponsored repression precipitated by the Cold War. Denied a reflection and shut off from the outside world by the darkness of the VR headset, the work complicates our own spectatorial embodiments by inducing feelings of motion sickness as we sink below the surface of the floor. Over roughly thirty minutes, Huang juxtaposes traditional Chinese imagery (such as burning lanterns and war junk) with the visible pixels and chunky polygons of primitive 3D digital animation, setting up an unsettling juxtaposition between an old world in crisis and a new one in the process of becoming.

Bodyless leverages the disjuncture between our cultural expectations of virtual reality as a seamless immersive experience with its technological limitations in practice. From the late-1990s, theorists have imagined virtual reality as an immersive medium ‘whose purpose is to disappear… within which the viewer should forget that she is in fact wearing a computer interface and accept the graphic image that it offers as her own visual world.’1 Contrary to this popular imagination of virtual reality as a seamless immersion in a wholly digital world, contemporary technologies are edged by seams that pull us out of the digital world before us: we feel the weight of the headset resting on our faces and see the black spaces at the periphery of our vision in the dark enclosure, constantly withdrawing us from the digital world before us.2 These seams complicate our spectatorial positions within the apparatus, setting up a tension between the digital world and our own embodied existences.

Rather than downplay the disjunctures of VR, Huang leverages them to generate uneasy and unsettling experiences. The work opens on the image of a body while devisualising the body of the spectator, further emphasising the disjunctive embodiments conditioned by contemporary virtual reality. Beyond its complication of the spectator’s embodied experience of the physical and virtual, the work also ruptures spatial continuity, transforming floors previously thought solid into permeable boundaries between spaces, forcing us to question what (if anything) is solid or certain within its world.

Across many of his works, Huang uses digital rendering to problematise the human body. His 3D printed series Sculptures of Touch (2022) scanned his own body in motion then fused these different poses into a single, undifferentiated mass. In Sculptures of Touch, Huang tried to record embodied memories of political repression, from hands searching for gaps in a prison wall (The Wall) to the movement of a prisoner struggling with one hand handcuffed to the floor (Handcuffs). As he notes in his artist statement for Sculptures of Touch:

Throughout my art career, "body memory" has been internalized as an element of my practice. What this series of works endeavors to discuss is the body memory of an era. The people of the last generation wore off the sharp, rigid system. The memory that came into being along the way is the greatest legacy left by the last generation. Nonetheless, these spiritual bequests left no traces at all in the official version of history.3

By playing up these uncertainties, Bodyless grapples with Taiwan’s reckoning with its own historical traumas and politically uncertain present. From the 1940s to the late-1980s, the Kuomintang ruled Taiwan as an authoritarian state, repressing democratic activism through a regime of mass surveillance, extrajudicial killing and arbitrary arrest. As this regime wound down with the relaxation of the Cold War, Taiwan became one of the most progressive states in East Asia with a flourishing democracy, advanced economy and inclusive approach to LGBTQI+ peoples, drawing stark contrast with its formerly repressive state. Parallel to this progressive present, Taiwan itself faces the geopolitical threat of invasion by the People’s Republic of China, whose international policies set out to undermine its cultural and legal status as an independent state through its constant reinforcement of the One China principle. Since 1971, the United Nations has formally recognised the mainland People’s Republic of China in place of Taiwan, further undermining its claim to sovereign statehood. Suspended in this state of ‘strategic ambiguity,’ Modern Taiwan lingers in states of disjuncture between its progressive present and repressive past, between its cultural and political independence and the threat of absorption by the PRC.

With Bodyless, Huang aligns the technological uncertainties of virtual reality with the cultural, historical and political uncertainties facing his home country to work through both while ultimately resolving neither. Instead, the work lingers in states of unsettled suspension, floating between past and future, the embodied violence of Taiwan’s repressive history and the complicated embodiment of virtual reality play.

1. Jay D. Bolter and Richard Grusin, Remediation: Understanding New Media (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999), cited in Richard Misek, “‘Real-time’ virtual reality and the limits of immersion,” Screen 61, no. 4 (Winter 2020): 615.

2. Daniel Golding, “Far from Paradise: The Body, the Apparatus and the image of contemporary virtual reality,” Convergence 25, no. 2: 340-353.

3. Hsin-Chien Huang, “Sculptures of Touch,” artist statement, accessed Thursday 5 October 2023, https://hsinchienhuang.com/pix/_3artworks/ds_sculpturesOfTouch/p0.php?lang=en.

Author/s: Duncan Caillard

Duncan Caillard. “Mediating Uncertainties: Digital Embodiment And Traumatic Pasts In Hsin-Chien Huang's Bodyless.” Art and Australia.com https://artandaustralia.com/A__A/p193/mediating-uncertainties

Art + Australia Editor-in-Chief: Su Baker Contact: info@artandaustralia.com Receive news from Art + Australia Art + Australia was established in 1963 by Sam Ure-Smith and in 2015 was donated to the Victorian College of the Arts at the University of Melbourne by then publisher and editor Eleonora Triguboff as a gift of the ARTAND Foundation. Art + Australia acknowledges the generous support of the Dr Harold Schenberg Bequest and the Centre of Visual Art, University of Melbourne. @Copyright 2022 Victorian College of the Arts The views expressed in Art + Australia are those of the contributing authors and not necessarily those of the editors or publisher. Art + Australia respects your privacy. Read our Privacy Statement. Art + Australia acknowledges that we live and work on the unceded lands of the people of the Kulin nations who have been and remain traditional owners of this land for tens of thousands of years, and acknowledge and pay our respects to their Elders past, present, and emerging. Art + Australia ISSN 1837-2422

Publisher: Victorian College of the Arts

University of Melbourne

Editor at Large: Edward Colless

Managing Editor: Jeremy Eaton

Art + Australia Study Centre Editor: Suzie Fraser

Digital Archive Researcher: Chloe Ho

Business adviser: Debra Allanson

Design Editors: Karen Ann Donnachie and Andy Simionato (Design adviser. John Warwicker)

University of Melbourne ALL RIGHTS RESERVED