The Mirror

EditorialAboutA+a Study CentreA+a ArchiveShopClose Menu

In 2021, the Bea Maddock Catalogue Raisonné: Volume Two, a digital listing of artworks made by Australian artist Bea Maddock, was gifted to the University of Melbourne. Compiled by Irena Zdanowicz, this catalogue is due for completion in 2024, when it will become freely available in perpetuity online. I interviewed Zdanowicz at her home to find out why catalogues raisonnés are so rarely undertaken in Australia, and to learn why Maddock’s catalogue has moved from a hard-copy book (in Volume One) to an online database (in Volume Two).

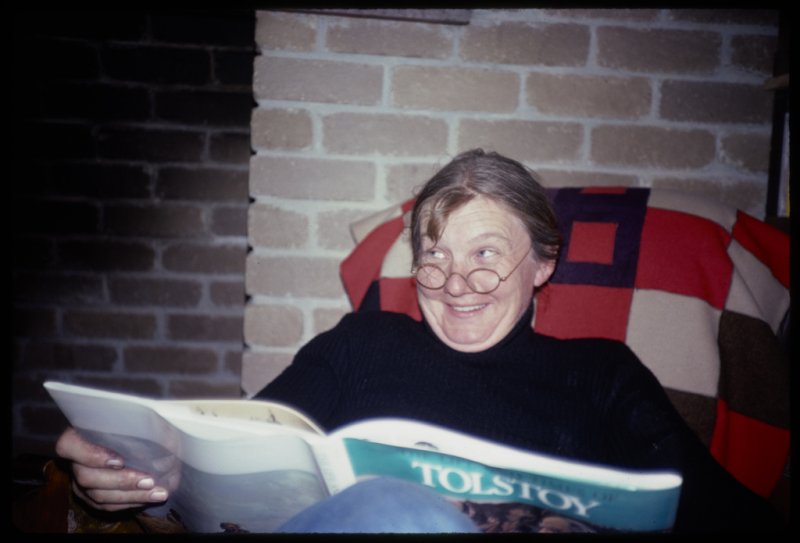

Bea Maddock’s art isn’t for everyone. She made artworks that are very still, with a heartbeat so calm and low that they might feel cold to the touch. For me however, she is a most precious artist. I welcome her crisp severity like the cool stone on the inside of a church. Interviewing Irena Zdanowicz, an eminent print curator and cataloguer of Maddock’s work, is a thrill for me. If I’m a disciple of Maddock, Zdanowicz is like Paul, the patron saint of writers for his authorship of the epistles in the New Testament, and the patron saint of missionaries for his evangelism. As appropriate for Maddock, Zdanowicz is a cool-headed follower—methodical and unwavering. She has spent fifteen years on this cataloguing project, beginning in 2008, when the artist was alive, and continuing on after the artist passed away in 2016.

Beatrice “Bea” Louise Maddock (13 September 1934–9 April 2016) was born in nipaluna/Hobart, in lutruwita/Tasmania, and grew up across various Anglican parishes where her father was a clergyman. While she might have abandoned religious dogma, the frugal structure of devout living stayed with Maddock throughout her life. Known in later years for her general asceticism, ‘Bea was very much a parson’s daughter’, Zdanowicz tells me.1 One of the most significant artists to come out of lutruwita/Tasmania, Maddock is also commonly adopted by people in Naarm/Melbourne, due to her legacy as a prominent teacher at the National Gallery of Victoria Art School (later the Victorian College of the Arts) from 1970–1981. This regional jockeying disguises Maddock’s national importance. In her heyday, curators and gallery directors unquestionably saw Maddock as ‘one of Australia’s most important contemporary artists.’2 Yet today, outside of loyal printmaking circles, Maddock is not well known, even in Australia. Maybe she’s destined to remain an artist for insiders—a secret shared among only the devoted.

On the day of our interview, Zdanowicz welcomes me into her home. Walking down the corridor, I am greeted by the print collector’s calling card, what I call ‘the print shrouds’. Over each artwork hanging on the wall, Zdanowicz has draped a crisp white cloth. It’s an amusing approach to display—hiding what you want to exhibit—but the cloths protect the delicate paper artworks from light exposure. In my experience, this faintly absurd scene is a sure sign that you’re absolutely in the right place. Whatever they’ve got under there, you know is worth seeing.

One work is uncovered when I visit. I wonder if Zdanowicz has uncovered it especially for the interview. I recognise it immediately as a single panel from Maddock’s late-career magnum opus, TERRA SPIRITUS ... with a darker shade of pale (1993–1998). When the full artwork is displayed, it takes up a whole gallery, 51 sheets in total that depict an accurate coastline of lutruwita/Tasmania to scale. Maddock wrestled with this work for five years, writing to friends that making it was ‘like trying to discipline 51 unruly children ... each unit wants to take off in its own’.3 Evidently, the individual sheet hanging in Zdanowicz’s hall is one that was deemed too unruly. This panel was a failure, and to show this, Maddock crossed out the image with a large zig-zag over the top. Printmakers will often use a simple, declarative symbol like a X to cancel (but not destroy) a work. The artist gifted it to Zdanowicz, yet—due to the cross-out—it is a real gift, but it is not a real artwork. Or rather, it is a non-work. It exists, but it should not be counted as a piece of art by Maddock. It is a waste product. As I will come to learn, sorting out what is interesting waste and what is important art is one of Zdanowicz’s key responsibilities as a cataloguer.

After spending fifteen years on this project, Zdanowicz’s digital catalogue raisonné has become part of her.4 She speaks laterally, her eyes slipping off to the side during conversation, as she recalls entries and items that might answer my question. She is thinking, I realise, in hyperlinks. All the muscles in her head and hands are primed for the task of delivering information about Maddock. For example, each time she wants to show me something she lifts her hand to touch the screen showing the catalogue. But Zdanowicz is using a different computer from the one she normally uses, which is a touch-screen. Awkwardly, this laptop is not a touch-screen, and we both sit as she tap-taps on various links, while nothing happens. We laugh each time her muscle-memory is finally overruled and she remembers to grab the mouse instead. The neural pathway is too engrained. She wields the database like a steering wheel.

Our first stop is TERRA SPIRITUS. This is because, Zdanowicz tells me, the entire Bea Maddock catalogue raisonné exists thanks to this piece. ‘People were asking how she did TERRA SPIRITUS, because {her techniques were} so unusual.’ The work is a series of editioned drawings that feature printing techniques, but are nevertheless largely hand-scored, hand-rubbed, hand-drawn and hand-written. Its bright orange hue is due to the natural local ochre that Maddock rubbed into the paper as a substitute for more commonplace printing ink. A combination of landscape and text-art, TERRA SPIRITUS required a systematic study of about 5,000 kilometres of coastland, alongside research on settler transcriptions of the languages spoken by Aboriginal peoples from lutruwita/Tasmania, which Maddock handwrote across the landscape in a flowing script, above local English placenames, which are stamped below in letter press. Beyond the conceptual force of TERRA SPIRITUS, it is an object of immense technical curiosity. Curators and conservators wanted to know: how did she physically make this object? After this question was posed, Zdanowicz recounts, a related question inevitably arose when looking at Maddock’s oeuvre of idiosyncratic artmaking: ‘how did she make any of this?’ A catalogue raisonné was soon proposed under the auspices of the Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery (QVMAG) in Launceston.

Catalogues raisonnés are one of the most rigorous and demanding projects that an art historian can undertake. Accordingly, they represent a pinnacle of research in the discipline of art history. In book-form or otherwise, a catalogue raisonné is a list of an artist’s total output, everything they have ever made. This pedantic list can be restricted to a specific medium or can span their entire oeuvre. The first volume of Maddock’s catalogue raisonné was compiled by Daniel Thomas, Theresa Mulford, cataloguers at QVMAG, and Maddock herself. It contains Mulford’s biography of Maddock’s life from birth until 1983, along with the detailed list of artworks, which are plotted against Maddock’s movements in Europe and at home. Excellent catalogues raisonnés—and Volume One is superb—make you feel like you are standing a few steps behind the artist as they pick up their tools to make one artwork, before putting them down to start sketching the next. You follow their processes from month to month, day to day, in an intimately diaristic manner.

The translation of Volume Two into an online publication has forced Zdanowicz to become a local authority on scholarly, digital catalogues raisonnés. Instead of writing a book that you can buy, her database will result in a website that readers can navigate for free. Pivoting to this model has made her task different to the researchers who came before her. Yet she is committed to the value of the online catalogue raisonné, betting on the mutability and freedom of a digital archive, over the elitist planned obsolescence of an expensive physical publication. In her search for the right proprietary software for Maddock’s work, Zdanowicz has closely examined many international online catalogues raisonnés, the numbers of which are steadily rising. The field will hopefully flourish into a new open-source golden age of this meticulous form of art historical scholarship.

Yet this idealistic hope stands in contrast to the reality that, historically, catalogues raisonnés were developed to serve the art market. They are a technology advanced by connoisseurs who wanted to explain the significance of any one particular Rembrandt, or Dürer, or Picasso. As journalist Katrina Strickland writes in her study of Australian artists’ estates: ‘The vast majority of catalogues raisonnés are for artists in Europe and United States. Surprisingly few Australian artists have one.’5 Catalogues raisonnés are usually created to meet the needs of a motivated secondary market, thus Australia’s relatively sluggish resale economy has rarely produced these costly publications. The exceptions prove the rule, with the great majority of the Australian catalogues raisonnés devoted to artists who, at one time or another, have been stalwarts of local auction houses: Brett Whiteley, Norman Lindsay, Margaret Preston, John Brack, Tom Roberts, Paddy Bedford, and more. It is the art market who needs catalogues raisonnés the most, and it is market forces that usually produce them. Zdanowicz points me to the fact that her work has been greatly funded by the Gordon Darling Foundation and major private donors including the late Frances Maddock and the late Beth Parsons.

Cynically, you could say, catalogues raisonnés appear in the service of increasing consumer confidence—more money, in the long run, falling after the auctioneers’ gavel. Yet, Maddock has never been a strong presence in the secondary market. Certainly, there are other motivations for undertaking the arduous catalogue raisonné process. Scholarly curiosity is one. For Zdanowicz, the catalogue also represented a good professional challenge. It was curiosity about her technical processes was enough to kick-start her catalogue in the early 2000s. But then there are more personal motivations—many scholars are driven by emotions like devotion, admiration, and loyalty. While tender feelings might propel a catalogue raisonné, these emotions are neatly sublimated under the dispassionate academic task of ordering, labelling and listing. The cataloguer might cross the division between personal and professional responsibility so many times that the line becomes smudged, even erased completely.

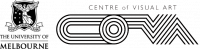

Zdanowicz was Maddock’s friend. Zdanowicz joined the National Gallery of Victoria (NGV) as a junior curator in 1968, moving to the Prints and Drawings Department in 1972, where she worked with Sonia Dean and Bridget Whitelaw. Maddock moved to Melbourne to teach in 1970. The artist was a frequent guest in the NGV’s renowned Print Room, where she would regularly examine the collection, either alone or with her students. Conversation with the print curators also offered a respite for the artist. ‘She was the only female teacher’, Zdanowicz reminds me (she was, in fact, the first female instructor in the art school’s history since its foundation in 1859). Nestled within the NGV’s considerable print collection, the female-dominated Print Department gave Maddock a break from a faculty that could be competitive and macho.

Zdanowicz begins her catalogue where Thomas and Mulford’s ends, after the 1983 Ash Wednesday fires that destroyed Maddock’s home and studio in Macedon in rural Victoria. This fire also destroyed the majority of Maddock’s artworks that were not already in private or public collections. Maddock had narrowly escaped the bushfire, fleeing with her dogs in her truck. She drove next morning to the NGV, where colleagues anxiously waited for news from the artist. ‘I distinctly remember the moment’, Zdanowicz says, ‘I was in the Print Room, and I turned, and she came in the door. And I said something like, “what’s happened?”, and she just said, “it’s all gone”.’ This experience is covered in Volume One of the catalogue raisonné; each lost work concluding with: ‘Destroyed in the Macedon bushfire 1983.’

In the recording of lost artworks, a catalogue raisonné insists on the value of something that is both undisplayable and unbuyable. The peculiar poetry of this choice appears when Thomas describes a very early artwork that was listed in Volume One as (Title withheld): ‘painted around 1955, destroyed {by the artist} three years later, never exhibited and hence not necessary for inclusion is nevertheless {recorded} here.’6 It is the activity of the artist, and the meaning they imbue into each piece, that the cataloguer describes. Thomas included (Title withheld), c.1955, because the title (whatever it had been) was a palindrome—a virtuosic, ambidextrous form, important to the artist later. Its existence, therefore, was acknowledged as a heraldic blast.

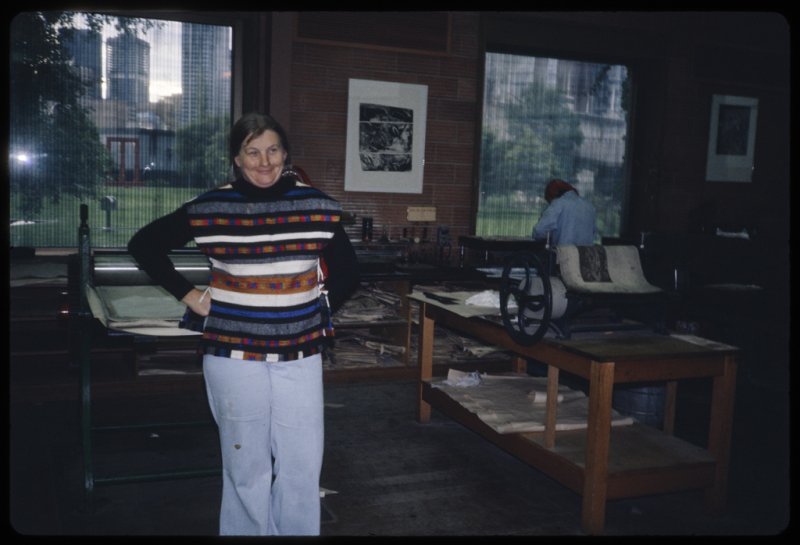

I assumed that after an artist experienced an event of unintentional ruin, they might lose their stomach for intentional destruction. Once a natural disaster has stripped you of your home and possessions, might a person develop an instinct for preserving, maybe even hoarding, what’s left? Not so, claims Zdanowicz. In the aftermath, Maddock made two self-portraits of herself fleeing the bushfires. She subsequently destroyed these sketches. Then, Zdanowicz shows me the digital record for a joyful little artwork. It is a Christmas card based on a staged photograph. It shows Maddock using an axe and is annotated: ‘BM. chopping up pictures circa 1985!!’ We can’t quite see her mouth, but it wouldn’t be hard to imagine the artist smiling. A sense of gleeful destruction is at the heart of this light-hearted work.

‘{Maddock} was delighted with Volume One’, Zdanowicz recalls, ‘but after she had reflected on it, she told me that some of the entries could have been omitted.’7 Emboldened by this mandate, Zdanowicz has taken up her own metaphorical axe, and developed a more decisive attitude to minor and lost works. For example, the lost drawings Maddock made of herself fleeing the fire are listed in Volume One, but Zdanowicz might not have included them as artworks. She says, reflecting on the artist’s right to obliterate a work, ‘what was the artist’s intention in destroying the work? If she thought them unsuccessful, and destroyed them for this reason, should they go into the catalogue?’ Zdanowicz is asking me this, but it is a question she has had to answer. An artist can gleefully destroy a work, but a cataloguer must justify their decision to remove a work from the oeuvre, hands wringing all the while.

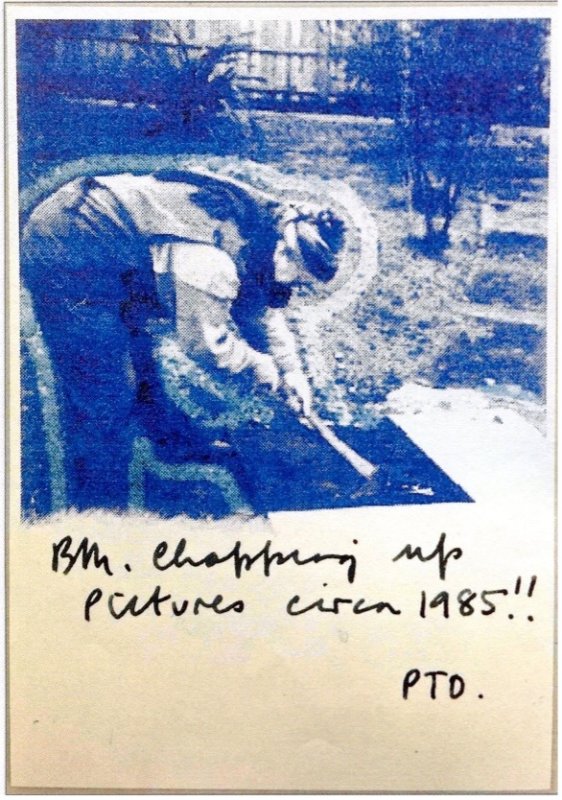

The Macedon bushfire occurred on 16 February 1983. Zdanowicz’s catalogue does not begin here, or even during the immediate aftermath of 1983, which saw Maddock making very few artworks, living in a hotel in the country town of Arnold in regional Victoria, and buying a new home in nearby Dunolly. The Macedon fire had burnt down a home/studio that Maddock had commissioned. It was a building tailored to her exact needs. There, Maddock had created an Access Studio, where her ex-students from Melbourne could visit and make prints in a well-appointed and peer-focused space. As far as the artist’s modest material desires went, Macedon was planned as a kind of personal utopia.

Maddock reflected on the destruction of Macedon with a hint of penitence; the wish-fulfilment of the perfect home/studio had ended in a necessary humbling. ‘The loss of Macedon was a cleansing thing’, Maddock wrote, ‘The Access Studio and the stylish building had not worked out; next time I would get it right, go cheap, and go back to a job in Launceston.’8 Volume Two begins with the artist having relocated to lutruwita/Tasmania, and starting again as the Head of the Art School at the Tasmanian College of Advanced Education.

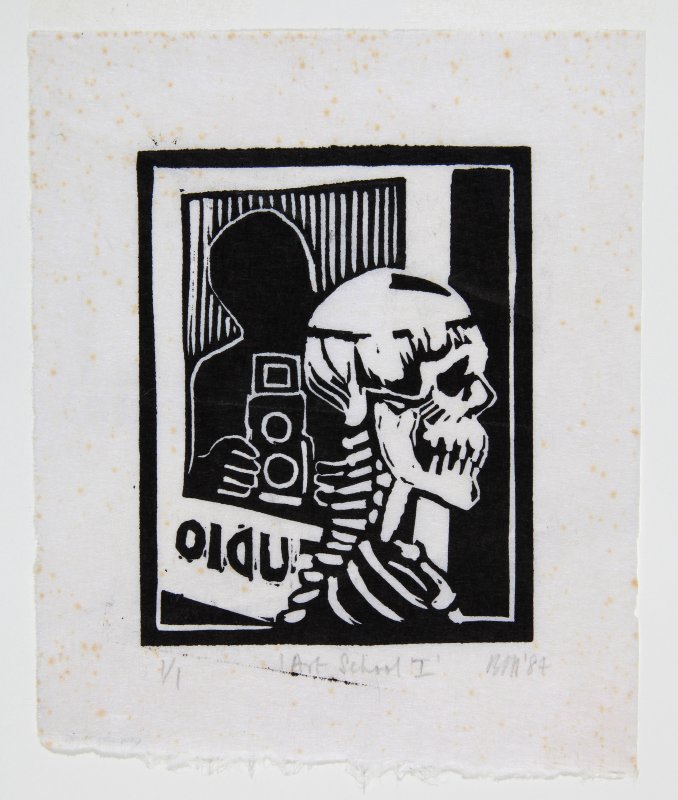

The first item in Zdanowicz’s catalogue is a parting shot at 1983. Art School I, 1984, is a linocut made at the art school print workshop in Launceston, where she was ‘back to earth after the misplaced ambitions of the Macedon studio.’ (After this she adds simply, to underscore her own hubris, ‘Icarus.’).9 We find the artist in a black, cynical mood. In the foreground: the skull of a skeleton, perhaps used by students for anatomy sketching. In the background: a depiction of the poster Maddock had made for the Macedon Access Studio. The poster features a self-portrait of Maddock hovering slightly behind the skull.

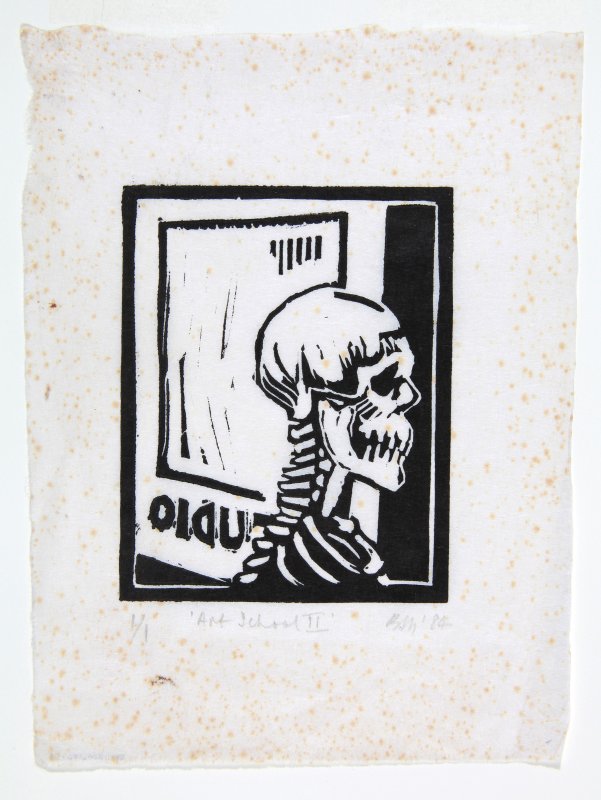

You could chalk it up to black humour—an omen of death and a poster advertising a workshop that had burnt to the ground. But the second artwork in Zdanowicz’s catalogue twists the knife a little further. Art School II, 1984, is a reworked second state of the first print, but this time, Maddock has removed the self-portrait present on the original poster. Yet, this self-erasure is a somewhat misleading beginning of the second act of her career. Volume Two follows Maddock’s work as it gets progressively more ‘Maddockish’—even more ambitious, more original, more eccentric.10 These intensifications could occur only after Maddock called it a day on her day-job—she resigned from her new teaching position after only twelve months, in acknowledgement that she could no longer lead an art school and be the artist she wanted to be at the same time.

In the years between 1984 and 1987, Maddock made a series of major works twinning two purgative experiences—having her work destroyed in the bushfire and quitting full-time teaching. The fire was a straightforward trauma; Maddock made work about it both directly and indirectly for years. But ever since she began instructing students in 1962, she was dismayed by the way teaching stole hours from her artistic work. Far from work-shy, Maddock wanted to labour in the studio rather than the classroom. In 1984 she made art that itched with frustration about the compromises forced by a 9-to-5. After quitting, she made work about the great release from those compromises.

Maddock began Philosophy Tape, 1984; 1987, while still working at the art school. As she had done before in an earlier work, this piece involved transcribing text from Jean-Paul Sartre’s Being and Nothingness. In Philosophy Tape she copied out the famous existentialist text on a roll of paper tape from an adding machine. As Zdanowicz records, her homage to Sartre was made at a time when,

‘Maddock felt she had reached a point when she might succumb to the routine of making the type of art that was expected of her—pictures to be framed and hung on a wall— instead of the kind of art she really wanted to create.’11

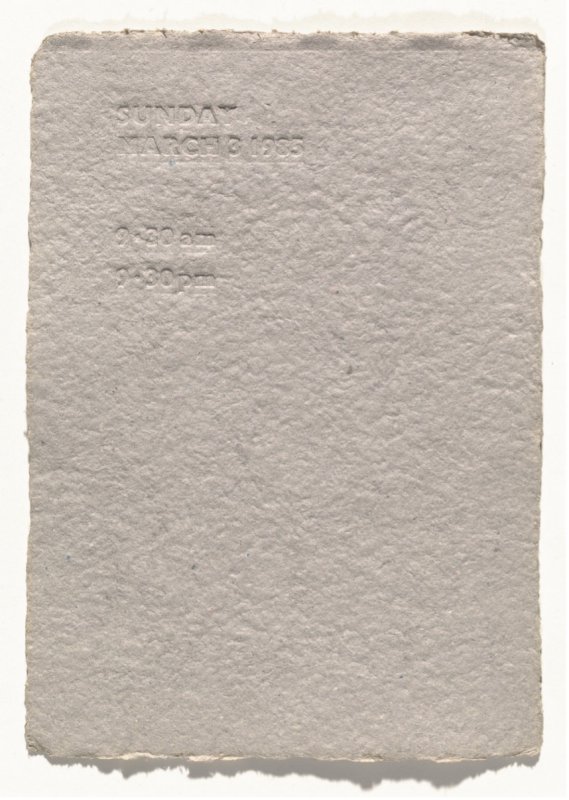

The making of Philosophy Tape represented another kind of resistance, a refusal to give up her practice despite the exhaustion of her job: ‘I used to come home late and … after teaching and running the art school the only thing I could do was to write out text’.12 It’s an obstinate, stubborn gesture against her draining profession. In the face of this mundane, social sorrow Maddock resolved to turn ‘resolutely inward, to expression that was private and contemplative in nature’.13 So, what did Maddock, a workaholic, do when released from the yoke of employment? Following her resignation, artworks like Impressions of Forty Working Days, 1985, Marking Time, 1985; 1987, and Thirty Days and Forty Nights, 1985, unleashed an increasingly esoteric preoccupation with the parcelling of life into discrete units of time. Free to devote the time she needed to her art, her art became devoted to the time that she had needed.

From 1984, language appears to take over Maddock’s practice, with almost every major work featuring text. Maddock’s use of text was largely citational, either quoting others or herself (via her daily journal). To the Ice, 1991-92, is comprised of lengthy passages derived from the artist’s diary that recorded a fateful journey she made to Antarctica in 1987. Her engagement with European philosophy receded and was replaced by a focus on the Old Testament, particularly Genesis, and the New Testament, particularly Christ’s forty days in the wilderness. Yet her return to religious texts was not restricted to the material she was raised on as a parson’s daughter.

The major piece, Thirty days and forty nights, 1985, is a puzzle-work in the form of thirty “flags” that chart events in Maddock’s daily life (such as the construction of a chimney) at her new home in Dunolly, alongside cryptic quotations that Zdanowicz worked hard to match to their original sources. In 1992, a reviewer cherry-picked one phrase (‘We have too much of everything’) as a statement that aligned Maddock with ‘more politically radical feminists such as Jenny Holzer and Barbara Kruger’.14 But what are we to make of the rest of the citations? Zdanowicz’s catalogue takes the reader through each flag, showing that much of the text reflects the durational logic of Eastern Arabic arithmetic and scientific observation, Jain cosmology and Koranic translation. Puzzles are solved by demonstrating that Maddock sourced the wide array of quotations from comparatively few publications. Thirty days and forty nights is a meditation with three or four significant books.15 Providing a better picture of Maddock among her sources is the key to this enigmatic work. Through Zdanowicz’s notes, we see how the artist was searching for transcultural principles that might annotate her own intense and hermetic manner of being in the world.

In her catalogue, under the description of each artwork, Zdanowicz found it necessary to transcribe whatever Maddock quotes, as a way of repeating the activity that the artist engaged in: ‘I’ve done that deliberately—however laborious it is—in order to understand what it is that she did. And I think unless you do that you can’t really understand it, and you can’t explain it {to others}.’ When I point out that readers can examine Maddock’s text-art in the high-resolution photography that documents every artwork in the catalogue, Zdanowicz counters that not every image is readable. An internet search engine, for example, cannot word-search an image. Some text is in different languages. Some is intentionally hard to read: Maddock occasionally blind-embossed text, printed words in white ink or wrote in a quick, light scrawl, so the reader must work to follow her meaning. The ease of searching keywords, phrases and quotations across Maddock’s career is a clear advantage of the digitised Volume Two. But beyond any benefit for the reader, Zdanowicz saw the catalogue transcriptions as a ritualistic process, one that helped her get close to the artist, ‘Bea read the words and she transcribed every single one. and {the words} mean something.’

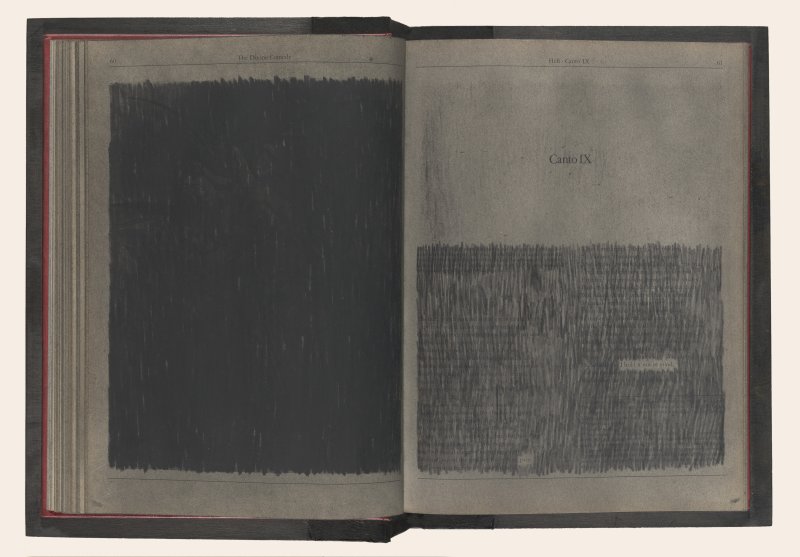

The erasure poem, The Divine Comedy, 1984–88, is Maddock’s first major work dated after the Macedon bushfire. An artist’s book, The Divine Comedy is created by blacking out the first 100 pages of Dante’s epic poem, leaving just 72 words visible. The remaining text can be read as Maddock’s own poem, which appropriates Dante’s departed lover as a displaced version of the artist: Maddock’s poem begins, ‘Beatrice / Myself’, and ends: ‘teach me / silence / the nature of the place, / deep within me – my words’. Zdanowicz notes that it was a coincidence that Maddock started this work the year after Tom Phillips, one of the most influential artists of erasure poetry, published his own treatment of Dante’s Inferno. It is not Zdanowicz’s place to venture a comparison of the two projects, but her catalogue raisonné provides all the material that future scholars will need to mount such an analysis.

Ultimately, Zdanowicz believes the crowning achievement of Maddock’s career is the work she created between 1987 and 1998, which uses text to address Aboriginal immemorial presence in lutruwita/Tasmania and Naarm/Melbourne. TERRA SPIRITUS is the pinnacle of this subject, and is one of the most important works of landscape art made by a settler artist. Layered over a meticulous circumnavigation of the island, Maddock relentlessly juxtaposes settler placenames with placenames derived from various colonial sources on Aboriginal languages throughout lutruwita.

As a settler acknowledgement of Indigenous country, TERRA SPIRITUS was recognised immediately as an important body of work, with editions one to five acquired for five national and state institutions in Australia (a sixth edition, the artist’s proof, was bequeathed to the Art Gallery of South Australia, Adelaide). This is surely the only time in Australian art history that a single work has been acquired simultaneously, en masse by multiple institutions.

Since the 1990s, all known Tasmanian Aboriginal (palawa/pakana) languages have been revived into a single language, named palawa kani. While Maddock’s intention was to write Indigenous consciousness onto the skin of the earth, and although using palawa kani geographical placenames is now encouraged for ‘all residents of lutruwita, and beyond’, Maddock’s research was derived from colonial primary sources and N. J. B. Plomley’s 1990 publication Tasmanian Aboriginal Place Names. Therefore her transcriptions inevitably contain what are now considered ‘inauthentic forms of the {palawa kani} language’.16 The catalogue raisonné will feature an essay responding to Maddock’s work by poet, art historian and descendant of the Trawulwuy peoples, Dr Greg Lehman, who has been providing guidance in relation to palawa kani and other matters of cultural sensitivity to Tasmanian Aboriginal people.17 Further interpretation of the substantial use of Indigenous language in Maddock’s art is the next great research project that Volume Two calls for.18 All of Maddock’s work using Aboriginal languages (including TAURAI … but in the memory of time, 1989, which contains text from the mainland Kulin nations) are in prominent public collections. These institutions could lead the necessary commission of further scholarship on Maddock’s late work.

Maddock completed no major works after TERRA SPIRITUS was completed and editioned. The mammoth task had left this most restless artist fulfilled in an unexpected way. What did Maddock turn to after 1998? The last ‘work’ in Volume Two of the catalogue raisonné, is really Volume One, which Maddock worked on from 2000 to 2011, when it was published. This effort of self-chronology forms an epilogue to her career, and this is visible in Volume Two when Maddock’s artistic production suddenly drops in the early 2000s. Alongside her collaborators in Volume One, Maddock spent the last years of her life historicising her own work.

In light of Maddock’s self-cataloguing, I suggest to Zdanowicz that her activity as Maddock’s last cataloguer has brought her very close to the kind of activity Maddock herself engaged in. She transcribes what Maddock transcribed, she studies the books Maddock studied, she looks with Maddock-eyes on Maddock’s art, to find out what readers need to know about the artist, her actions, and her decisions. After all these years, there is a part of Zdanowicz that has become ‘Maddockish’, by necessity of the task at hand.

As she shows me around her archive, I keep returning to the idea of Zdanowicz shadowing Maddock. I continue to press this line even after we’ve finished our interview, and Zdanowicz pauses, finding the words that might articulate their differences. When she speaks, she describes Maddock’s final, utilitarian lodgings. A humble, austere set-up: small bed, simple kitchen where she could bake her own bread, piles of books in organised disarray, and maybe a poster of a beloved painting on the wall. I understand that Zdanowicz is drawing a portrait of Maddock’s life through the things she did without: luxuries of any kind, creature comforts. She had close family members, but they did not live with her. She lived like a monk or a priest, really. ‘I couldn’t live like that’, Zdanowicz insists. ‘I think she was a real radical. And she was radical not in the flag waving sense. But in the sense that she led her life exactly as she wanted to, without compromising ... She’s just a very admirable person, for me.’

The curator and the artist are different beasts, after all; one follows the other. The artist walks ahead, determining the path and the pace, while the curator is obliged to stoop and collect whatever they cast behind them. Those of us who follow artists do so because we admire them and believe they might be showing us the way. A catalogue raisonné charts this relationship better than any other kind of scholarship. Volume Two is the project by which future generations will come to know Maddock, as Zdanowicz’s catalogue is destined to become the most accessible resource on the artist. While I navigate through the generously detailed database that she has created, it is equally clear that Volume Two will become the project by which future generations of art historians also come to know Zdanowicz. Maddock’s body of work exists in the world, but it is the flow of admiration that runs through the intimate and convoluted scholarship of Zdanowicz, and others, who connect us to it.

1. All quotations from Zdanowicz, unless otherwise stated, are from Irena Zdanowicz recorded conversation with Victoria Perin, 23 August 2023, author’s collection.

2. Betty Churcher, ‘Preface’ Betty Churcher, ‘Preface’ in Roger Butler and Anne Kirker, Being and Nothingness: Bea Maddock – Work from three Decades, exhibition catalogue (Brisbane/Canberra: Queensland Art Gallery and Australian National Gallery, 1991), p.7

3. Bea Maddock as quoted by Irena Zdanowicz, ‘From page to screen: The catalogue raisonné in the digital age’, symposium keynote lecture [transcript], Prints, Printmaking and Philanthropy, University of Melbourne (1 October 2019), p.8.

4. During the development of the Maddock catalogue raisonné, Zdanowicz also published the much admired Rick Amor: An Online Catalogue Raisonné of the Prints. The database software that is being used for the Maddock project is the specialist catalogue raisonné software created by the North American company, panOpticon.

5. Katrina Strickland, Affairs of the art: love, loss and power in the art world (Carlton: Melbourne University Publishing, 2013), p.84.

6. Daniel Thomas and Therese Mulford, Bea Maddock: Catalogue raisonné. Volume 1, 1951-1983 (Launceston: Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery, 2011), p.23.

7. Zdanowicz, ‘From page to screen: The catalogue raisonné in the digital age’ (2019), p.9.

8. Thomas and Mulford, Bea Maddock: Catalogue raisonné. Volume 1, 1951-1983 (2011). p.266.

9. Ibid., p.268.

10. Zdanowicz records the artist using the adjective ‘Maddockish’ in the catalogue record for Artifacts from Tromemanner, an artist’s book from 1990.

11. Catalogue record for Philosophy Tape, 1984;1987, pencil and graphite stick on paper tape in an artist-made acrylic and plywood box, 24.5 x 25.8 x 25.0 cm. Collection: Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery, Launceston. Gift of Bea Maddock, 2001.

12. Bea Maddock, quoted in Butler and Kirker, Being and Nothingness: (1991), p.100.

13. Catalogue record for Philosophy Tape, 1984;1987.

14. Felicity Fenner, ‘Belated nod to printmaking ground-breaker of the ‘70s’, The Sydney Morning Herald, 28 March 1992, p.49.

15. Zdanowicz lists Maddock’s major sources as: John Penrice, A Dictionary and Glossary of the Koran, with Copious Grammatical References and Explanations of the Text (New Delhi: Cosmo Publications, 1978; first published 1873 (London)); Seyyed Hossein Nasr, Islamic Science: An Illustrated Study (London: World of Islam Festival Publishing, 1976); and, Colette Caillat & Ravi Kumar, The Jain Cosmology, trans. R. Norman (New York: Harmony, 1981).

16. See Tasmanian Aboriginal Centre’s ‘pulingina to lutruwita (Tasmania) Place Names Map’, first published 2019 (https://tacinc.com.au/pulingina-to-lutruwita-tasmania-place-names-map/), and Policy and Protocol for Use of palawa kani Aboriginal Language, 2019 (https://tacinc.com.au/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Policy-and-Protocol-for-Use-of-palawa-kani-Aboriginal-Language-2019-1.pdf).

17. Other contributors to the catalogue raisonné include the art historian David Hansen, the artist Jan Senbergs and the conservator Louise Wilson.

18. The catalogue raisonné will also include a concordance of Tasmanian Aboriginal place names featured in Maddock’s art, which will be updated as new palawa kani and dual place names are made available.

Author/s: Victoria Perin

Victoria Perin. “Bea Maddock Catalogue Raisonné: Volume Two By Irena Zdanowicz.” Art and Australia.com https://artandaustralia.com/A__A/p208/bea-maddock-catalogue-raisonn-volume-two-by-irena-zdanowicz

Art + Australia Editor-in-Chief: Su Baker Contact: info@artandaustralia.com Receive news from Art + Australia Art + Australia was established in 1963 by Sam Ure-Smith and in 2015 was donated to the Victorian College of the Arts at the University of Melbourne by then publisher and editor Eleonora Triguboff as a gift of the ARTAND Foundation. Art + Australia acknowledges the generous support of the Dr Harold Schenberg Bequest and the Centre of Visual Art, University of Melbourne. @Copyright 2022 Victorian College of the Arts The views expressed in Art + Australia are those of the contributing authors and not necessarily those of the editors or publisher. Art + Australia respects your privacy. Read our Privacy Statement. Art + Australia acknowledges that we live and work on the unceded lands of the people of the Kulin nations who have been and remain traditional owners of this land for tens of thousands of years, and acknowledge and pay our respects to their Elders past, present, and emerging. Art + Australia ISSN 1837-2422

Publisher: Victorian College of the Arts

University of Melbourne

Editor at Large: Edward Colless

Managing Editor: Jeremy Eaton

Art + Australia Study Centre Editor: Suzie Fraser

Digital Archive Researcher: Chloe Ho

Business adviser: Debra Allanson

Design Editors: Karen Ann Donnachie and Andy Simionato (Design adviser. John Warwicker)

University of Melbourne ALL RIGHTS RESERVED