The Mirror

EditorialAboutA+a Study CentreA+a ArchiveShopClose Menu

In this article, Jason Lee imagines how Howard Morphy might discuss the Saltwater collection of paintings from Yirrkala to a Paiwan readership. Originally published in art&Australia, March 2001, pp.420-7. You can read the original article below.1

大部分Yolngu(雍古族)人居住在Arnhem Land(阿納姆地) 東部的海岸和內陸河流沿岸散佈的小聚落中。民國 89年,乾季,一位知名的Madarrpa(馬答爾帕族)藝術家去世了,他的名字至今尚未被提及。他以畫作和雕刻Bäru(巴鲁)—— 祖鱷魚——而聞名。Bäru的家位於藍泥灣 (Blue Mud Bay) 北部的Yathikpa(亞蒂克巴)和Garrangali(加蘭加利)。在他臨終之際,他的同族人唱起了祖鱷魚的神聖歌曲。Bäru以歌從河口進入海洋,隨著潮汐返回岸邊,到鱷魚今天築巢的河口水道。合唱的同時,Madarrpa老人的靈魂與Bäru的靈魂融為一體,隨著潮汐的漲落而移動,意味海水,品嚐淡水和鹹水混合的滋味,感受境外潮流的強大力量。Yolngu喪葬儀式中,逝者的靈魂與創造土地的先祖力量團聚,並被帶回神靈家園。Yolngu儀式帶來了這種精神回歸的安慰。靈魂成為那個祖先力量寶庫的一部分,為陸地和海洋等地點供給能量,並提供激勵新一世代的精神力量。Yolngu生活包含了一種在生與死之間、祖傳或Wangarr(旺加爾)之間的持續交流。與當下世界的不斷交換,這種交換以歌曲、神聖名字、物品和畫作來作為媒介。

Bakulangay Marawili(巴庫蘭蓋.馬拉維利)的畫作《Yathikpa II》,於民國 86年-民國87年創作,描繪了Yathikpa海域並記錄了其祖先歷史。Bäru沒有以具,但在氏族的菱形圖案中卻隨處可見,佔據了背景的主要圖案。Bäru將火帶入了世界。他在Yathikpa起火──大火蔓延開來,燃燒了整國度。Bäru本人也被困在大火中。他的身體著火,潛入海中,火焰擴散到水面,使其翻滾沸騰。Bäru最終把火留在Marrtjala(馬爾賈拉)海潮之下,在那仍然繼續燃燒。Bakulangay 的畫作著重於Burrak(布拉克)和Munuminya(穆努米尼亞)儒艮獵人—兩位Madarrpa的精神祖先—生活的關鍵一幕。他們在Marrtjala海域看到一隻儒艮在海中游動,他們看到海草在水面下像火焰般移動。他們製作了一支魚叉,坐上獨木舟出海。用魚叉猛擊儒艮,但在儒艮死亡的痛苦中,儒艮拖著獨木舟和獵人一起沉入水底。獵人於火岩仍在燃燒的波濤深處身亡。獨木舟隨著潮汐漂回海岸,化成離岸岩石,而巨型魚叉在海中翻腾,向該地區的族人傳遞死亡的消息。魚叉轉又成為了與放置死者骨骼的空心原木棺材類似的物體 。

這幅畫不是對神話事件的真實再現,而是對其的一種冥想形式。它是以概念性的代表,也是根植於土地的想法。這幅畫傳達了狩獵的理念:海上發現了儒艮;準備好魚叉;儒艮被刺殺。它提到了海洋的危險:水流湍急、儒艮的力量。它指向鱷魚創造火的故事,以及土地的所有權。畫作中心代表了獵人的視線方向、魚叉的軸心,儒艮拉動船隻時的繩子。在頂部中央的分割線上,既複製刺殺儒艮的過程,又展示了魚叉杆改變成空心棺材的過程,這是死去獵人的遺體容器,充滿了Madarrpa的菱形圖像。在水平面上,對稱性被背景設計的變化形式和對角裁切的圖像所破壞。這裡的背景設計傳達了火勢的兇猛和與大海湍流中的類似效果。我們可以感受到潮汐的拉扯,幾乎看到船隻被儒艮的俯沖所淹沒,從畫中的直線撕裂。背景設計的各部分既指涉了海域的不同部分,也指涉了與神話有關聯的不同的氏族:菱形的織帶屬於Madarrpa,而環繞著儒艮和獨木舟的波浪線代表了Manggalili(曼加利利族)、Dhalwangu(達爾萬古族)和Madarrpa的水源匯聚。這些符號象徵暗示故事的細節——用繩子連接到紅樹木浮筒的空船,或者提供從陸地觀看的視角——在湍流中游動的儒艮。這幅畫的含義是更廣泛地理解人與地之間關係的一部分,它與Yathikpa的歌曲、神聖名稱和神聖地理的相互聯繫息息相關。

民國85年10月,Djapu(賈普族)的Wäka Mununggurr(瓦卡.蒙農古爾)在Yathikpa發現了一些金目鱸魚漁民的非法營地,藏匿在紅樹林中。這個營地裡有燃料桶、食物殘餘和寢具,但還有一個更悲慘的入侵紀念品——一隻鹽水鱷魚的斷頭。儘管在海岸的某些地方,Yolngu法律允許捕殺鱷魚作為食物,但在這個區域——鱷魚的精神家園——這樣的殺戮是一種褻瀆行為。鱷魚Bäru是Madarrpa神聖祖先,體現在地景的形式中。這一事件是《鹹水》畫作的催化劑之一。《鹹水》畫作是一組從南部的藍泥灣到北部的Arnhem Bay(阿那姆灣)的Yolngu藝術家創作的大型樹皮畫。

Yolngu從歐洲人開始在該地區殖民以來,就一直致力於保護他們海洋的權利。他們長期以來爲獲得澳大利亞法律規定的土地權利,而進行的長期鬥爭是有着豐富的記錄 。民國52年他們首次意識到,他們的土地受到鋁土礦業的威脅,他們向議會提出的樹皮請願書,開啟了一個漫長的政治行動和說服過程,對弗雷澤(Fraser)政府於民國65年通過土地權利立法做出了重大貢獻。然而,該立法僅涵蓋了土地上的權利。對於Yolngu來說,海洋和陸地是密不可分的。作為沿海獵人和採集者,他們的海洋權利與承認土地權利同樣重要。《鹹水》畫作反映了他們的心思,並詳細記錄了他們對海洋及其文化和社會意義的所有權。正如Dula Ngurruwutthun(杜拉.恩古魯烏通)所寫:

「這是我們的法律,也是我們的藝術。通過繪畫,我們在向您講述一個故事。從太古以來,我們就一直在繪畫,就像您用鉛筆書寫一樣。是的,我們利用我們的知識來進行繪畫,從遠古的家園直到大海的底部。」2

海洋和陸地是相互關聯的,沿著岸邊畫出的任意線條在很大程度上是歐洲人的概念。環境主要由雨季和旱季之間的季節性變化所主導,以及從內陸流向海洋的淡水和潮汐帶來的鹹水的流動。同樣的远古生物隨著潮汐向內陸移動,隨著洋流和洪水流向海洋。Baluka(巴盧卡)的畫作《Manggalili Monuk曼加利.莫努克》,創作於民國86年-民國87年,追隨著Mayawundji(馬亞溫吉)內陸沼澤的水流,那裡狗追逐老鼠,鷺鷥注視著,經過閃電蛇的鹹水平原,進入海灣再到大海。在遠處,遠古海龜在魚和奇異的海怪中嬉戲著,引起風,把水氣吸起成高聳的雲,在地平線上高高地像鐵砧般突兀地站立著。這些水氣轉而回到陸地,帶來了濕季的風暴,釋放閃電蛇,帶來更新的降雨。

對於Yolngu來說,海洋與陸地一樣豐富多樣。在Yolngu的世界裏,一個核心的分界點是兩半-「Dhuwa」(杜瓦)和「Yirritja」(伊里賈)。Dhuwa娶Yirritja,反之亦然,而孩子跟隨其父親的社會所屬的那一部分 。Dhuwa和Yirritja的關係就像是子母關係,pothu(波圖)和yindi(因迪)。氏族屬於其中一個,動植物物種不是Dhuwa就是Yirritja,土地也是Dhuwa或Yirritja,水體也同樣被劃分。Gawirrin Gumana(加維林.古馬納)的畫《Djarrwark ga Dhalwangu賈爾瓦克.達爾萬古》,於民國86年-87年創作,描繪了Yathikpa旁邊海灣的海域。畫作的頂部勾勒出了海岸線,在畫的中心是Yirritja屬性的水域,用尖圓形表示從Baraltja(巴拉爾賈)的河口流出。這些水域被偉大的蛇Mundukul(姆杜庫爾) ,推向海灣,並在下部面板上呈現Yirritja屬性的圖像。在頂部面板上Yirritja屬性的水域屬的兩側是Djarrwark(賈爾瓦克族)的水域,Dhuwa屬性,以水平和垂直線條的圖案表示。在祖先時代,Djang'kawu(姜卡烏)姐妹使用她們的獨木舟上划越這片水域而上岸。同樣的氏族圖像標記了一個橢圓形,代表著Yirritja屬性的河水流過的低矮沙洲:Dhuwa和Yirritja,母親和孩子。

在Raymangirr Arnhem Bay(雷曼吉爾阿納姆灣),Dhuwa和Yirritja的水合二爲一 。聖神的水從河流流入海灣,潮則將鹹水吸入海灣。來自不同地理的水帶著它們所來之處的特徵相互碰撞,波濤洶湧,引起強大的洋流和波浪,在某些地方形成漩渦,在另一些地方形成泡沫噴泉。Mowara Ganambarr(莫瓦拉.加南巴爾)的畫作展示Mäṉa(瑪納) 在Rorruwuy(羅魯烏伊)的Dhuwa祖鯊魚,他負責攪動水域,並用尾巴拍打水面。這些水域屬於通婚的氏族。水是屬於Dhuwa屬性──包括Ḏäṯiwuy(達蒂烏伊族)和Ngaymil(內米爾族)──和Yirritja屬性──Wanguri(旺古裏族)和Gumatj(古馬其族)。在某個地方,名為gandjipa(甘吉巴)的Yirritja水域降落在正在沉睡的祖鯊魚上,並喊道:“嘿,我落在什麼上面了?” Dhuwa鯊魚回答道:“媽媽,是我,我在睡覺。請打斷我的尾巴。請別踩我的眼睛——我很敏感,很容易被激怒。”2

祖先所創造的海洋及其中地方是洪荒之力的源泉,與擁有它們的氏族密切相關。神話記載許多人就是從海中誕生的。正如Langani Marika(蘭加尼.馬里卡)所寫:“孩子的靈魂有可能來自海水。它有可能首次以海洋生物的形式顯現,比如海龜或魚帶來意外財富。這是我們的宗神信仰。”3 海洋中的某些地方是特定祖先相關的精神力量蓄積地,也是受孕靈魂的源頭。它們提供了祖先過去與今天氏族成員之間的連續性。Mr. Wanambi( 萬安比先生)的畫作《Bamurrungu巴穆倫古》,於民國86年-87年創作,與Djuwany(朱瓦尼)相關聯的精神力量幾乎要以在小徑灣 (Trial Bay)一塊神聖岩石成群結隊的「garrawa」魚(加爾瓦)──橢圓斑點珊瑚魚──的形式爆發出來。魚象徵著受孕靈魂,而這幅畫將嬉戲能量與生育和繁殖的形象相結合,唤起了這個地方孕育生命的特質。

Yolngu藝術中,大自然的力量被融入了洪荒之力量的圖像之中,反映Yolngu對世界的前景、對海洋及其危險的了解、對其力量和壯麗以及其生產力來源的欣賞。大自然為人類生命有限性和死亡的必要性、生命的更新以及世界的連續性提供了豐富的隱喻。Dhukal Wirrpanda(杜卡爾.維爾潘達)的畫《Gapuwarriku at Lutumba加普瓦里庫在盧通巴》,於民國86年-87年創作,描述海龜獵人們帶著他們的獵物返回。這故事與之前捕儒艮的獵人的故事不同,但海龜的故事也成為了喪禮儀式圖像的基礎,這次是Dhuwa部分的喪禮儀式。海龜殼就像身體的骨骼;海龜繩是象徵著把人們聚集在一起進行儀式的聯繫形象;潮汐把海龜獵人帶回海岸,並在沙灘上洗淨海龜身體,為淨化儀式提供了豐富的畫面;海龜將蛋埋在沙子中,那就是生命出現的地方。

Yolngu的生活歷史於他們在陸地和海洋上的旅程中得以描繪,他們的生存基於對環境的密切了解。這種知識具有社會和精神的層面,這與Yolngu人瞭解世界的方式以及他們管理資源所遵循的規則密不可分。他們的畫作在很大程度上是海洋的地圖:標誌著人與地之間的關係,用氏族圖像的織錦覆蓋海洋和陸地,展示了人們在當地擁有的權利,並有助於和平地利用海洋資源。海洋是雍古社會世界的一部分。正如 Langani Marika所說的:“我們的血緣將我們與海洋中的所有事物聯繫在一起。它承載着我們的家庭。海洋中的一切都是相關聯的。4

我要感謝 Andrew Blake, Pip Deveson, Frances Morphy和 Will Stubbs对本篇文章的協助。

註釋

本文當時給作者提供了以下簡介:「Howard Morphy(霍華德.莫菲)是澳大利亞國立大學跨文化研究中心的教授兼主任。他在藝術人類學、美學、表演、博物館人類學、視覺人類學和宗教等方面發表了大量論文。他的著作包括《祖先之聯繫:藝術與澳洲原住民知識系統》(芝加哥大學出版社)和《原住民藝術》(Phaidon)。」

本文中所提供的作品照片來自澳大利亞國家海洋博物馆收藏。若未經藝術家或提供者授權,不得摘錄或轉載圖片。有關作品資訊,請參閱澳大利亞國家海洋博物馆網上目錄https://collections.sea.museum/objects/165179/saltwater-collection

文獻中Yolngu語的詞通常未被翻譯。本文中提供的詞彙乃是音譯版本,而非官方翻譯。以下是為了這篇文章所拼的音譯詞:

音譯詞-族名

Ḏäṯiwuy (達蒂烏伊族)

Dhalwangu (達爾萬古族)

Djapu (賈普族)

Djarrwark (賈爾瓦克族)

Gumatj (古馬其族)

Madarrpa (馬達爾帕族 )

Manggalili (曼加利利族)

Ngaymil (內米爾族)

Wanguri (旺古裏族)

音譯詞-人名

Bakulangay Marawili (巴庫蘭蓋.馬拉維利 )

Baluka (巴盧卡)

Dhukal Wirrpanda (杜卡爾.維爾潘達)

Dula Ngurruwutthun (杜拉.烏魯烏圖圖恩)

Gawirrin Gumana (加維林.古馬納)

Langani Marika (蘭加尼.瑪麗卡)

Mowara Ganambarr (莫瓦拉.甘巴爾)

Wäka Mununggurr(瓦卡.穆農古爾)

音譯詞-祖靈故事名詞

Burrak (布burr拉克)

Djang’kawu (姜卡乌)姐妹

Mäṉa (馬吶)

Mundukul (蒙杜庫爾)

Munuminya (穆努米尼亞)

音譯詞-作品名

《Bamurrungu巴穆倫古》

《Djarrwark ga Dhalwangu賈爾瓦.克.達爾萬古》

《Manggalili Monuk曼加利.莫努克》

音譯詞-地名

Baraltja (巴拉爾蒂亞)

Gandjipa (甘吉巴)

Garrangali (加蘭加利)

Marrtjala (馬爾賈拉)

Mayawundji (馬亞溫吉)

Raymangirr (雷曼吉爾)

Rorruwuy (羅魯烏伊)

Yathikpa (亚蒂克巴)

音譯詞-族語詞

Dhuwa (杜瓦)

garrawa (加爾瓦) –意:橢圓斑點珊瑚魚

Wangarr(旺加爾) – 意:祖傳

Yirritja(伊里賈)

Images 圖像

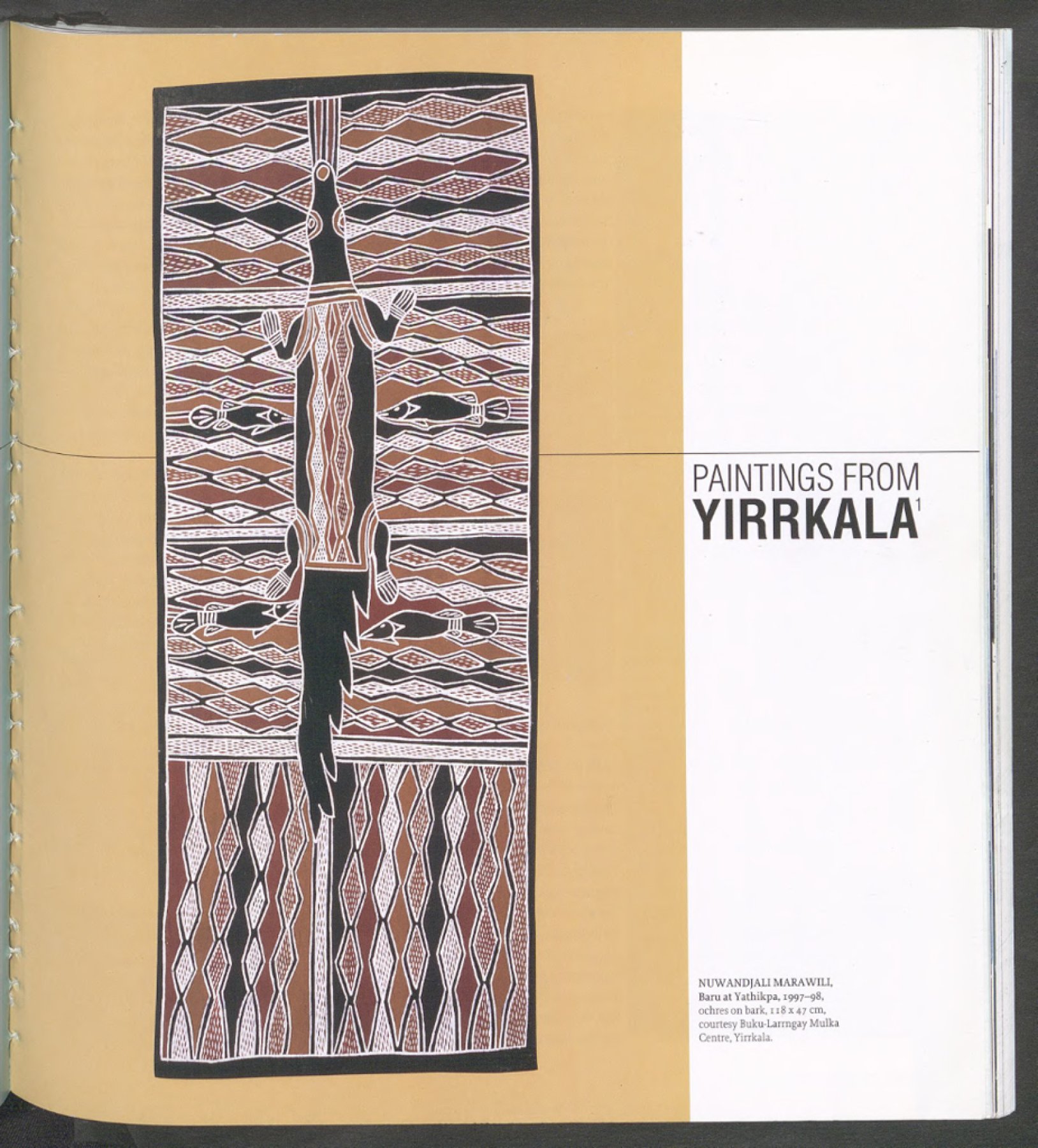

P。421(NUWANDJALI MARAWILI, Baru at Yathikpa, 民國86年-民國87年, 118 x 47 cm, 赭色繪畫,Buku-Larrngay Mulka中心 提供)

P。423 (BAKULANGAY MARAWILI, Yathikpa ll, 民國86年-民國87年, 赭色繪畫, 208 x 66cm, Buku-Larrngay Mulka中心 提供)

P。423 (BALUKA MAYMURU, Manggalili Monuk, 民國86年-民國87年, 赭色繪畫, 281 x 82cm, Buku-Larrngay Mulka中心 提供)

P。424 (GAWIRRIN GUMANA, Djarrwark ga Dhalwangu, 民國86年-民國87年, 赭色繪畫, 153 x 83cm, Buku-Larrngay Mulka中心 提供)

P。425 (MOWARA GANAMBARR, Mâna at Rorruwuy, 民國86年-民國87年, 赭色繪畫, 122 x 87 cm, Buku-Larrngay Mulka中心 提供)

P。426 (MR. WANAMBI, Bamurrungu, 民國86年-民國87年, 赭色繪畫, 186 x 81cm, 1998年國家與托雷斯海峽群島人美術獎得主,最佳樹皮繪畫,Buku-Larrngay Mulka中心 提供)

P。427 (DHUKAL WIRRPANDA, Gapuwarriku at Lutumba, 民國86年-民國87年, 158 x 80cm, Buku-Larrngay Mulka中心 提供)

1. 本文基於來自Yirrkala的「鹹水」收藏的樹皮畫。這些作品已被澳大利亚国家海洋博物馆收購。作品已被精確記載在畫冊中,鹹水: Yirrkala 繪畫海之國度的樹枝(Yirrkala和雪梨: Buku-Larrngay Mulka Centre和Jennifer Isaacs Publishing,民國 88年)。「鹹水」收藏與民國89年5月5日至5月9日在瓦浪悉尼澳大利亚国家海洋博物馆;民國89年8月19日至10月5日在烏倫傑理國海德現代藝術博物館;和民國90年12月2日至民國91年1月20日在Mparntwe愛麗斯泉阿拉倫中心展。

2. Dula Ngurruwutthun,《鹹水.宣言》,10。

3. Mowara Ganambarr,《鹹水.宣言》,17-18、84。

4. Larangi Marika,《鹹水.宣言》,19。

5. Larangi Marika,《鹹水.宣言》,19。

照片:David Silva 攝影作品

The Yolngu people, for the most part, live in small settlements on their clan lands, scattered along the coast and inland rivers of eastern Arnhem Land. During the dry season in 2000 a well-known artist of the Madarrpa clan died, too recently for his name to be written here. He was renowned for his paintings and carvings of Bäru, the ancestral crocodile, whose homes are at Yathikpa and Garrangali in the north of Blue Mud Bay. Towards the end, as he lay dying, his clansmen sang the sacred songs of the crocodile ancestor. In song, Bäru moved out from the river-mouth into the sea and then back with the tide to the shore, to his home in the estuarine channels where crocodiles make their nests today. As the songs were sung, the old man’s spirit became one with the spirit of Bäru, moving with the ebb and flow of the tide, smelling the sea, tasting the flavours of the fresh and salt waters as they mixed together, and feeling the powerful forces of the currents offshore. In Yolngu mortuary rituals a dead person’s spirit is united with the ancestral forces that created the land, and carried back to its spirit home. Yolngu ritual brings with it the consolation of this spiritual return. The soul becomes part of that reservoir of ancestral forces that energises certain places - on land and in the sea -and provides the spiritual force that animates new generations. Yolngu life involves a continual exchange between the living and the dead, the ancestral dimension or the Wangarr and the world of the here and now, an exchange that is mediated by song, sacred names, objects and paintings.

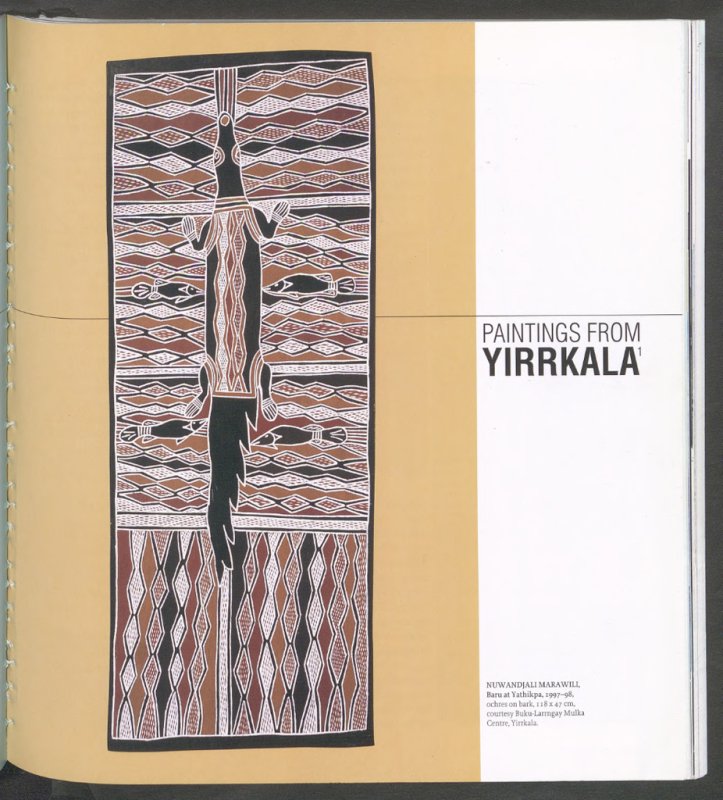

Bakulangay Marawili’s painting Yathikpa II, 1997-98, maps the sea off Yathikpa and records its ancestral history. Bäru is not represented in figurative form, but is everywhere present in the diamond clan designs that provide the dominant background pattern of the painting. It was Bäru who brought fire into the world. He created fire inland at Yathikpa - a great fire that spread and burnt the country. Bäru himself was caught in the conflagration. With his body on fire he dived into the sea and the flames spread across the water, causing it to boil and roar. Eventually Bäru left the fire beneath the waves at Marrtjala, where it continues to burn. Bakulangay’s painting centres on a key episode in the lives of the dugong hunters, Burrak and Munuminya, spiritual ancestors of the Madarrpa people. They saw a dugong out to sea swimming in the area of Marrtjala. They saw the sea grass moving like flames beneath the surface of the water. They made a harpoon and set out to sea in their canoe. They harpooned the dugong, but in the anguish of its death it dived deep beneath the surface of the water, dragging the canoe and the hunters with it. They died deep beneath the waves where the flames still burned from the rocks of fire. The canoe drifted back on the tide to be transformed into rocks offshore, and the giant harpoon tossed around in the sea carrying messages of the deaths to the clanspeople of the region. The harpoon in turn became an analogue for the hollow-log coffin in which the bones of the dead could be placed.

The painting is not a literal representation of the mythological events. Rather, it is a form of meditation on them. It is conceptual, and yet the ideas are firmly rooted in place. The painting conveys the idea of the hunt: the dugong are sighted out to sea; the harpoon is prepared; the dugong is speared. It refers to the dangers of the sea: the turbulence of the waters and the strength of the dugong. It refers to the creation of fire by the crocodile, and to the ownership of the land. The straight lines that run along the centre of the painting represent the direction of vision of the hunters, the shaft of the harpoon, the taut line of the rope as the dugong pulls the boat along. Where the line divides in the top central panel it both duplicates the spearing of the dugong and shows the transformation of the harpoon shaft into a hollow coffin, container of the bodies of the dead hunters, infilled with the diamond designs of the Madarrpa clan. In the horizontal plane the symmetry is disrupted by the changing form of the background design and the cross-cutting segments of design. Here the background design conveys the ferocity of the fire and its analogue in the turbulence of sea. We can sense the rip of the tide and almost witness the overwhelming of the boat as it was torn from its straight line by the dugong’s dive. The different segments of the background design refer both to different areas of sea and to the different groups who are connected by the story: the ribbons of diamonds belong to the Madarrpa clan, and the wavy lines around the dugong and canoe represent the coming together of the waters of the Manggalili, Dhalwangu, and Madarrpa clans. The figures hint at details of the story - the empty canoe connected by rope to the mangrove-wood float, or provide a view from the land - the dugong as they move about in the swirling sea. But the meaning of the painting is part of a wider understanding of the relationship between people and place that lies in its interconnection with the songs, sacred names, and the sacred geography of the landscape at Yathikpa.

It was in the area of Yathikpa in October 1996 that Wäka Mununggurr of the Djapu clan discovered, hidden in the mangroves, the illegal camp of some barramundi fishermen. The camp contained drums of fuel, food remains and bedding but also, in a hessian bag, a more tragic memento of their intrusion - the severed head of a saltwater crocodile. While on some parts of the coast Yolngu law allows the killing of crocodile for food, in this area - the spirit land of the crocodile - such a killing is an act of sacrilege. The crocodile, Bäru, is the spirit ancestor of the Madarrpa people themselves, embodied in the very form of the landscape. This event was one of the catalysts for the Saltwater paintings, a group of large bark paintings by Yolngu artists that covered the coastal waters from Blue Mud Bay in the south to Arnhem Bay in the north.

Yolngu have been concerned to protect their rights to the sea from the beginning of European colonisation in the area. Their long struggle to gain land rights under Australian law is well documented. Their bark petition to Parliament in 1963, when they first realised that their land was threatened through bauxite mining, began a long process of political action and persuasion which contributed greatly to the passage of land rights legislation by the Fraser Government in 1976. The legislation, however, only covered rights on land. To the Yolngu, the sea and land are inseparable. And, as coastal hunters and gatherers, recognition of their sea rights is just as important as the recognition of land rights. The paintings in the Saltwater Collection reflect their concern, and document in detail their ownership of the sea and its cultural and social significance. As Dula Ngurruwutthun wrote:

This is our law and our art. By painting we are telling you a story. From time immemorial we have painted, just like you use a pencil to write with. Yes, we use our knowledge to paint from the ancient homelands to the bottom of the sea.2

The sea and the land are interrelated and the arbitrary line drawn along the shore is very much a European construct. The environment is dominated by the seasonal alternation between the wet season and dry, and between the flow of fresh water from the inland to the sea and the movement of the tide bringing salt water back. The same ancestral beings move inland with the tide and out to sea with the currents and floodwaters. Baluka’s painting Manggalili Monuk, 1997-98, follows the flow of the waters from the inland swamps of Mayawundji, where the dogs chase the rats and the heron looks on, through the salt flats of the lightning snake, into the bay and out to sea. In the distance the ancestral turtle plays among fish and strange sea monsters, causing the wind that sucks the water up into clouds that stand high and anvil-like on the horizon. These in turn move back to the land, bringing with them the wet season storms that release the lightning snake and renewing rains.

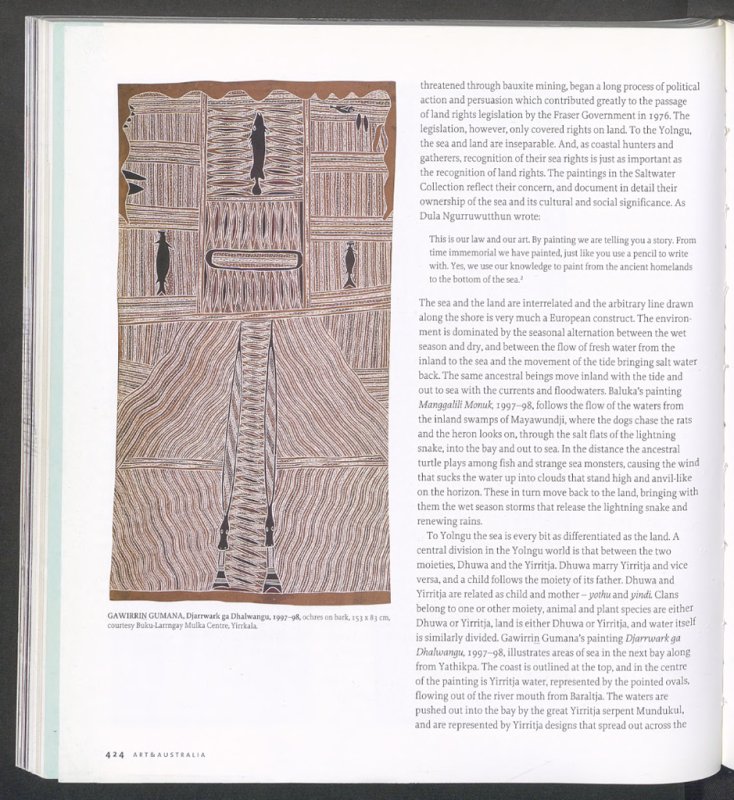

To Yolngu the sea is every bit as differentiated as the land. A central division in the Yolngu world is that between the two moieties, Dhuwa and the Yirritja. Dhuwa marry Yirritja and vice versa, and a child follows the moiety of its father. Dhuwa and Yirritja are related as child and mother - pothu and yindi. Clans belong to one or other moiety, animal and plant species are either Dhuwa or Yirritja, land is either Dhuwa or Yirritja, and water itself is similarly divided. Gawirrin Gumana’s painting Djarrwark ga Dhalwangu, 1997-98, illustrates areas of sea in the next bay along from Yathikpa. The coast is outlined at the top, and in the centre of the painting is Yirritja water, represented by the pointed ovals, flowing out of the river mouth from Baraltja. The waters are pushed out into the bay by the great Yirritja serpent Mundukul, and are represented by Yirritja designs that spread out across the lower panel. In the top panel to either side of the Yirritja waters are waters of the Djarrwark clan of the Dhuwa moiety, represented by the pattern of horizontal and vertical lines. In ancestral times the Djang’kawu sisters paddled these waters in their canoe before coming onshore and travelling inland. The same clan design marks an oblong shape representing a low sand bar over which the Yirritja waters flow: Dhuwa and Yirritja, mother and child.

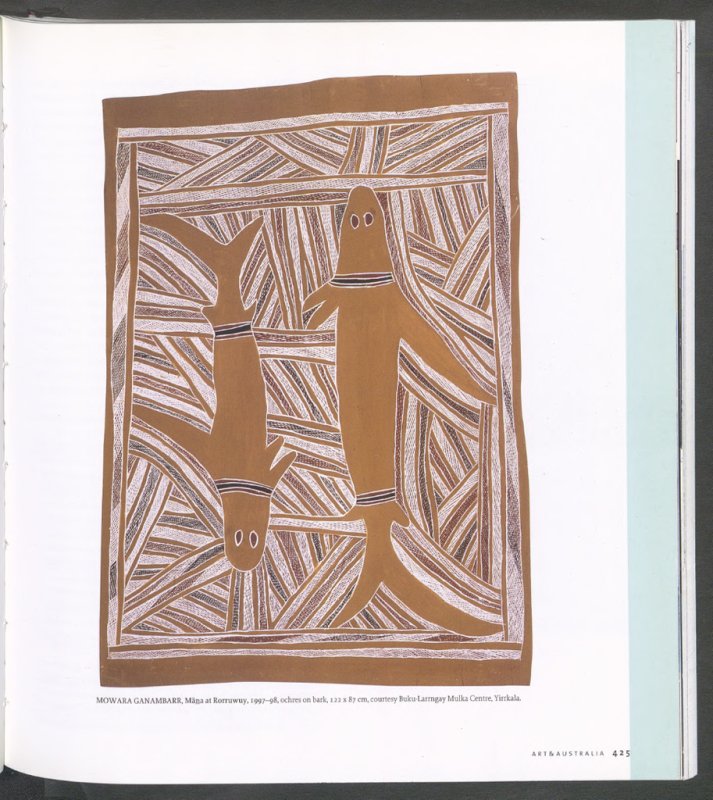

In Arnhem Bay, at Raymangirr, the Dhuwa and Yirritja waters converge. Ancestral waters flow into the bay from the rivers, and salt water is sucked into the bay on the tide. The waters from different directions bearing the identity of the places they have come from clash together, heaving and foaming, causing great currents and swells, in some places creating whirlpools and in others fountains of foam. Mowara Ganambarr’s painting shows Mäṉa the ancestral Dhuwa shark at Rorruwuy, where he is responsible for churning up the waters as he lashes about with his tail. The waters belong to clans that intermarry - to the Dhuwa clans, including the Dätiwuy and Ngaymil, and to the Yirritja, Wanguri and Gumatj clans. At one place the Yirritja waters called gandjipa landed on top of the sleeping shark and cried out: ‘Hey what did I land on?’. The Dhuwa shark replied: ‘Yes it is me mother, I was sleeping. You will not break my tail. Do not tread on my eyes -1 am sensitive and easily provoked.’3

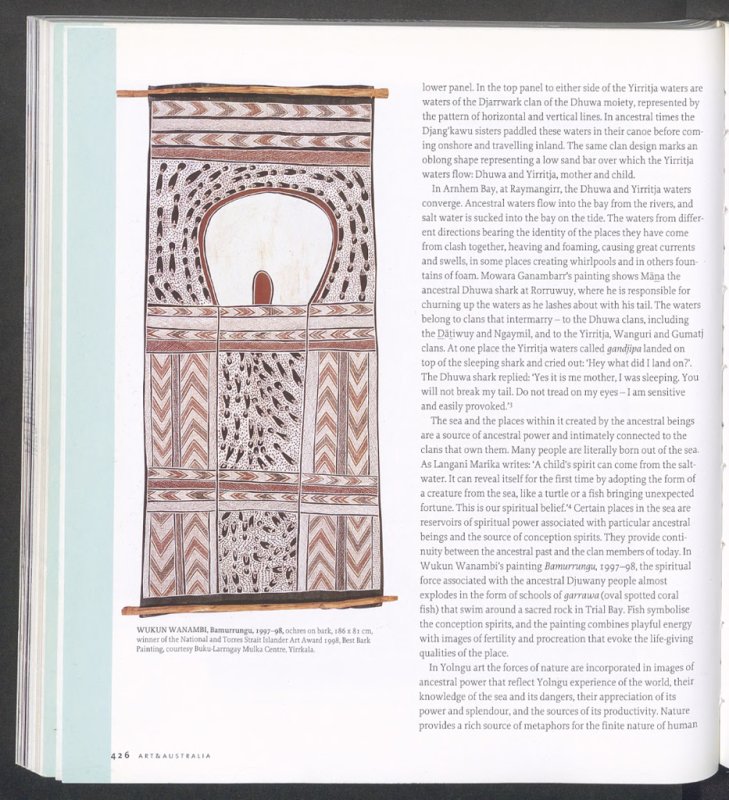

The sea and the places within it created by the ancestral beings are a source of ancestral power and intimately connected to the clans that own them. Many people are literally born out of the sea. As Langani Marika writes: ‘A child’s spirit can come from the saltwater. It can reveal itself for the first time by adopting the form of a creature from the sea, like a turtle or a fish bringing unexpected fortune. This is our spiritual belief.’4 Certain places in the sea are reservoirs of spiritual power associated with particular ancestral beings and the source of conception spirits. They provide continuity between the ancestral past and the clan members of today. In Mr. Wanambi’s painting Bamurrungu, 1997-98, the spiritual force associated with the ancestral Djuwany people almost explodes in the form of schools of garrawa (oval spotted coral fish) that swim around a sacred rock in Trial Bay. Fish symbolise the conception spirits, and the painting combines playful energy with images of fertility and procreation that evoke the life-giving qualities of the place.

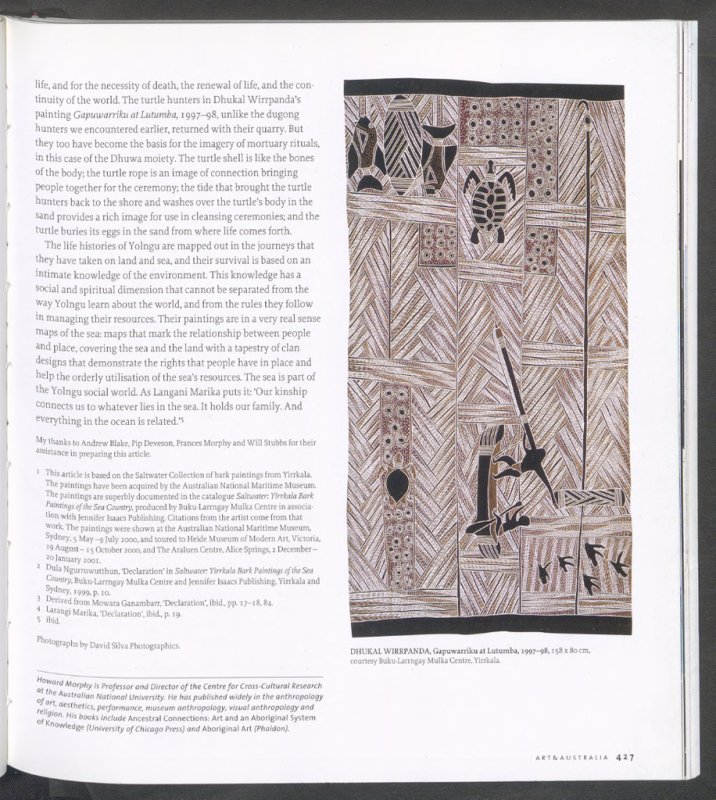

In Yolngu art the forces of nature are incorporated in images of ancestral power that reflect Yolngu experience of the world, their knowledge of the sea and its dangers, their appreciation of its power and splendour, and the sources of its productivity. Nature provides a rich source of metaphors for the finite nature of human life, and for the necessity of death, the renewal of life, and the continuity of the world. The turtle hunters in Dhukal Wirrpanda’s painting Gapuwarriku at Lutumba, 1997-98, unlike the dugong hunters we encountered earlier, returned with their quarry. But they too have become the basis for the imagery of mortuary rituals, in this case of the Dhuwa moiety. The turtle shell is like the bones of the body; the turtle rope is an image of connection bringing People together for the ceremony; the tide that brought the turtle hunters back to the shore and washes over the turtle’s body in the sand provides a rich image for use in cleansing ceremonies; and the turtle buries its eggs in the sand from where life comes forth.

The life histories of Yolngu are mapped out in the journeys that they have taken on land and sea, and their survival is based on an intimate knowledge of the environment. This knowledge has a social and spiritual dimension that cannot be separated from the way Yolngu learn about the world, and from the rules they follow in managing their resources. Their paintings are in a very real sense maps of the sea: maps that mark the relationship between people and place, covering the sea and the land with a tapestry of clan designs that demonstrate the rights that people have in place and help the orderly utilisation of the sea’s resources. The sea is part of the Yolngu social world. As Langani Marika puts it: ‘Our kinship connects us to whatever lies in the sea. It holds our family. And everything in the ocean is related.’5

My thanks to Andrew Blake, Pip Deveson, Frances Morphy and Will Stubbs for their assistance in preparing this article.

The following biography was provided for Tuckson in the frontmatter for this issue: “Howard Morphy is Professor and Director of the Centre for Cross-Cultural Research at the Australian National University. He has published widely in the anthropology of art, aesthetics, performance, museum anthropology, visual anthropology and religion. His books include Ancestral Connections: Art and an Aboriginal System Knowledge (University of Chicago Press) and Aboriginal Art (Phaidon).”

All artwork illustrating the pages of art&Australia are part of the permanent collection of The Australian National Maritime Museum. They are provided in context of the original article. Images should not be extracted or republished without prior permissions from the artists or rights holders. For more information about the artwork, please refer to the current The Australian National Maritime Museum catalogue:

https://collections.sea.museum/objects/165179/saltwater-collection

Footnotes

1. This article is based on the Saltwater Collection of bark paintings from Yirrkala. The paintings have been acquired by the Australian National Maritime Museum. The paintings are superbly documented in the catalogue Saltwater: Yirrkala Bark Paintings of the Sea Country produced by Buku-Larngay Mulka Center in association with Jenifer Isaacs Publishing. Citations from the artist come from that work. The paintings were shown at the Australian National Maritime Museum, Sydney, 5 May- 9 July 2000, and toured to Heidi Museum of Modern Art, Victoria, 19 August -15 October 2000, and the Araluen Centre, Alice Springs, 2 December – 20 January 2001.

2. Dula Ngurruwutthun, ‘Declaration’ in Saltwater: Yirrkala Bark Paintings of the Sea Country, Buku Larmgay Mulka Centre and Jennifer Isaccs Publishing, Yirrkala and Sydney, 1999, p.10

3. Derived from Mowara Ganambarr, ‘Declaration’, ibid. pp, 17-18, 84

4. Larangi Marika, ‘Declaration’, ibid, p. 19.

5. ibid.

Image captions

P.421: NUWANDJALI MARAWILI, Baru at Yathikpa, 1997-98, 118 x 47 cm, ochres on bark, courtesy Buku-Larrngay Mulka Centre, Yirrkala.

P.423: BAKULANGAY MARAWILI, Yathikpa ll, 1997-98, ochres on bark, 208 x 66cm, courtesy Buku-Larrngay Mulka Centre, Yirrkala.

P.423: BALUKA MAYMURU, Manggalili Monuk, 1997-98, ochres on bark, 281 x 82cm, courtesy Buku-Larrngay Mulka Centre, Yirrkala.

P.424: GAWIRRIN GUMANA, Djarrwark ga Dhalwangu, 1997-98, ochres on bark, 153 x 83cm, courtesy Buku-Larrngay Mulka Centre, Yirrkala.

P.425: MOWARA GANAMBARR, Mâna at Rorruwuy, 1997-98, ochres on bark, 122 x 87 cm, courtesy Buku-Larrngay Mulka Centre, Yirrkala.

P.426: Mr. WANAMBI, Bamurrungu, 1997-98, ochres on bark, 186 x 81cm, 1998, winner of the National and Torres Strait Islander Art Award 1998, courtesy Buku-Larrngay Mulka Centre, Yirrkala.

P.427: DHUKAL WIRRPANDA, Gapuwarriku at Lutumba, 1997-98, 158 x 80cm, courtesy Buku-Larrngay Mulka Centre, Yirrkala.

Photographs by David Silva Photographies.

鹹水國度:來自 Yirrkala(阿纳姆地)的畫 原文: Howard Morphy霍華德.莫菲 : Jason JS Lee

Saltwater Country - Paintings From Yirrkala : Howard Morphy

Jason JS Lee. “鹹水國度:來自 Yirrkala(阿纳姆地)的畫 原文: Howard Morphy霍華德.莫菲.” Art and Australia.com https://artandaustralia.com/A__A/pp222/-yirrkala-howard-morphy