Breakfast of Vulnerables

Without egg and bacon one cannot speak of the soul.(1) Meaning, then, that egg and bacon can act as a placeholder for what the sublime repudiates; egg and bacon as the volume of tourists at Kinkaku-Ji, egg and bacon as a grease-trap somewhere in Vatican City, egg and bacon as sand dunes cordoned off by fluorescent orange bunting, egg and bacon as an excavator in a cemetery, egg and bacon as the barely distinguishable scaffolding supporting each highfalutin endeavour to lift the soul.

No news there. It’s been a long time since the sublime was exchanged in popularity for the quotidian details that it necessitates. Repudiate the repudiator. That’s arguably why so many young artists’ Instagrams are composed mainly of things like tar on the sidewalk in the shape of a flower or a bit of tape leaving a gluey trail on a dusty window, as if noticing that which isn’t often noticed is actually a thing.

The (hazardous) upshot to valuing minutiae is manifold. It allows the spectacle to be undermined, disassembled, milked of potency and repurposed closer to the ground; egg and bacon as the sticky-tape under Trump’s tie. Furthermore, to value and accept the minuscule supports of the sensationalised world can demonstrate an engagement with the nebulous lineage of things. The gluey strip on the dusty window can only be traced through the possible histories of production and gesture. It is the lineage, then, that is thrown into contention, and by virtue of this the image itself. This can be a healthy attitude to cultivate amidst a ‘culture of denial’ and whizz-bang politics. However, it can become an exercise in denial itself. What begins as a means of antagonising or rejecting the illusion of the sublime (soul, spirit, spectacle) by finding value closer to the ground, proliferates and can become in many cases a benign reflex, an aesthetic, a husk. Michael Denning outlines the conceit of egg and bacon succinctly; ‘[…] the aesthetic of globalisation, [is] often as empty and contrived a signifier as the modernism and socialist realism it supplanted’.(2) It is easy to substitute modernism with sublimity, and sublimity’s brethren the soul and spectacle, considering the sublime was a founding principle of the movement. Egg and bacon means that the sublime is no longer meaningful because the illusion has been compromised. Similarly, egg and bacon itself is not meaningful in this context since it acts only as a means of undermining the sublime. The result is such that the perpetrator of egg and bacon avoids being scrutinised for sincerely valuing the sublime but consequently offers no alternative avenue for meaning or a proposition to emerge.

Judith Williamson in her 2008 Frieze talk titled ‘The Culture of Denial’ said ‘The visual is the perfect vehicle for deknowing,(3) with its capacity for collapsing together opposites, for displacing emphasis and turning negatives into positives.’(4) This seems like an ideal place to discuss egg and bacon as/in artistic practice. Things that appear markedly unpoetic in the traditionalist sense (powerpoint fonts, video game consoles, revivalist internet aesthetic, dollar store items, branded foodstuff, gluey windows) have, in some cases, reached a point of ubiquity in artistic practice that they have begun to operate as an (let’s be generous) unintentional stratagem to sidestep actual content. The items become a placeholder in themselves, as if referencing mass produced consumables, entertainment equipment, lifestyle choices and quirky incidentals, critiques or comments on consumer content interaction, globalisation, the information age, the global proliferation of data et cetera. If anything the reference reinforces the subject of the critique’s presiding presence in our lives.

Before hackles are raised, I’m not suggesting it is down to the specific components of a work to determine when something slips into vacuity. All I’m attempting to outline is that there is the risk of a tendency for objects and/or motifs, beholden to a certain aesthetic, to become shorthand for, say, globalization and so forth. Motifs and aesthetics aside, many practices operate similarly, painting for example allows disparate sources to be collated together, layered, erased, revealed, hinted at. Here, the risk is run of these processes and aesthetic conclusions becoming shorthand for an attitude towards history that celebrates conjecture. This, in turn, can be presented as addressing narrative of all sorts (political, national, historical) as tenuous and constructed. However, this effectively amounts to nothing more than a gesture of criticality. By signifying narrative as tenuous and constructed no content can be scrutinized. The reason being that under such a conception of narrative meaning is dependent upon the individual and if everything is contingent on conjecture then nothing is really meaningful. Subsequently, the work avoids having to be held accountable for the images it portrays, since if narrative is as malleable as the work aims to suggest then essentially ‘anything goes’. The work sets itself up to not be able to fail by proposing meaning and simultaneously undermining its own position. It says and does nothing yet affects the pretense of ‘criticality’.

These shorthands pose one of the more negative ramifications of what Williamson posits. The aforementioned ‘unpoetic’ aesthetic has the capacity to displace emphasis away from what the object/motif/component references or embodies and places it instead on referencing the reference; turning a negative, not into a positive exactly, but into a neutral. Similarly the collapsing together of opposites painting affords, through processes such as collage, can nullify the specifics of each component (displacing emphasis) with the good intention, presumably, of addressing image relationships, histories, coincidence.

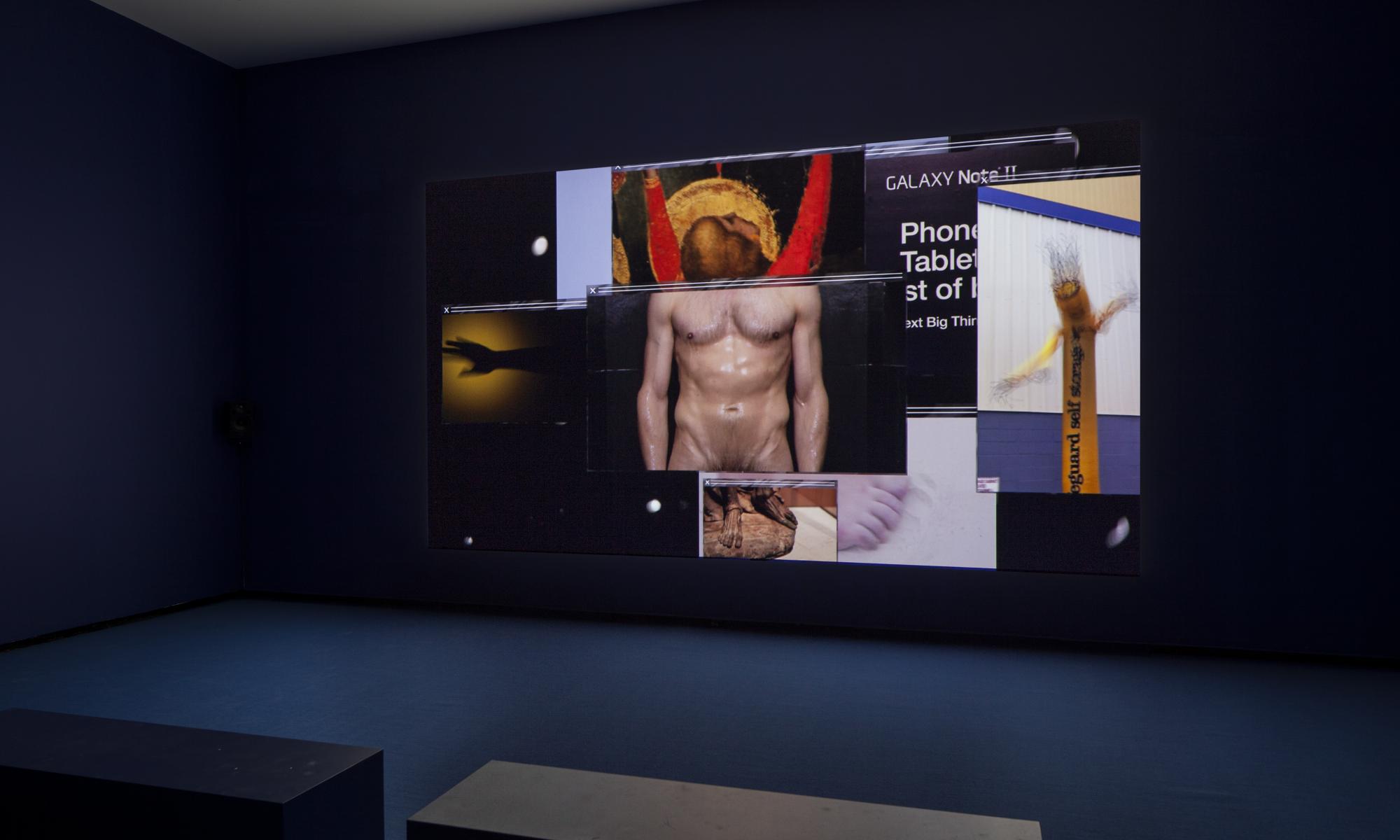

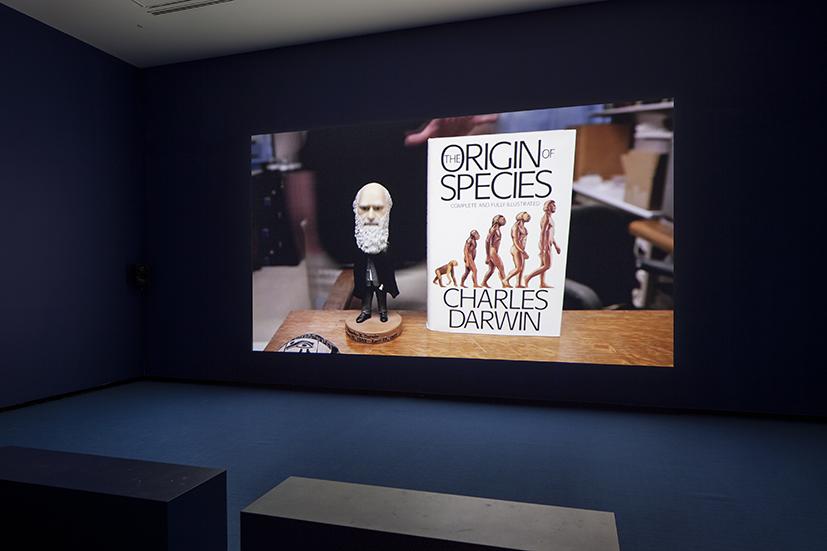

Melbourne was lucky enough to have Camille Henrot’s Grosse Fatigue (2013) installed at ACCA at the beginning of 2016. Visitors to the show it was a part of (The Biography of Things), or anyone who has seen the work or excerpts elsewhere, will know that the backdrop for the film is an Apple Mac desktop, upon which images and videos are layered. Each visual fragment of the work exists in an unmistakably OS X pop up window. Egg and bacon as personal computer.

Henrot’s practice has been described (by whoever wrote the 20th Sydney Biennale bios) as ‘[…] challenging the traditional categorisation of art history’ and ‘[…addressing the] way western historical perspectives borrow and appropriate from other cultures.’(5) This seems reminiscent of an attitude towards history that valuing of egg and bacon facilitates; the nebulous lineage of things. Furthermore, the actual video couldn’t be more overt in its collapsing together of opposites and displacing of emphasis. However, I feel this work circumvents the snares that have been sketched thus far.

Let’s focus on the historical perspectives as an outcome of the work. Certainly, the montage of hands rifling through biologists’ specimens, anthropological artefacts and artists’ monographs, overlaid with a rap incorporating several creation myths, presents a palpable web of conflicting narratives. The way the film unravels and the way the audio operates rescues the work from relying solely on collage and disparate imagery as a means of conveying this. There are parameters. These manifest in the narrative unfolding through the audio, and in the subjects of each visual component, which refrain from being a chaotic display of random imagery. Instead they offer a considered sequence of events that invites a futile sort of join-the-dots approach to viewing, never too ambiguous, never too overt. It is filmed well and composed precisely. This all conspires to make for hypnotic watching. So, the collage flits between a montage of tangential, conflicting histories (representation), and fulfilling its own distinct narrative (actualisation). The work doesn’t just represent a world, but creates its own. It’s arguable that this is only possible through vulnerable processes, namely, a sincere and idiosyncratic vision that only when realised can invite scrutiny of the functionality of its components. It is this pull between two states (representation vs. actualisation) that saves the work from becoming a nullified form referencing a reference. Similarly, the timing and composition of each Mac OS X pop up window has an affinity with actual personal computer use; scrolling, minimising, closing, opening, enlarging. Part of the reason the rhythm of the work is so mesmerising is because of this affinity—it transcends the trope of the consumerist aesthetic by utilising it in a way that mirrors actual use. Mac OS X ceases being a static placeholder for data flow and consumerism and becomes activated through affinity. The viewer becomes actively engaged in a conversation on, say, the global flow of data and history by virtue of this activation. They are no longer receivers but participants. The work stops pointing and acts.

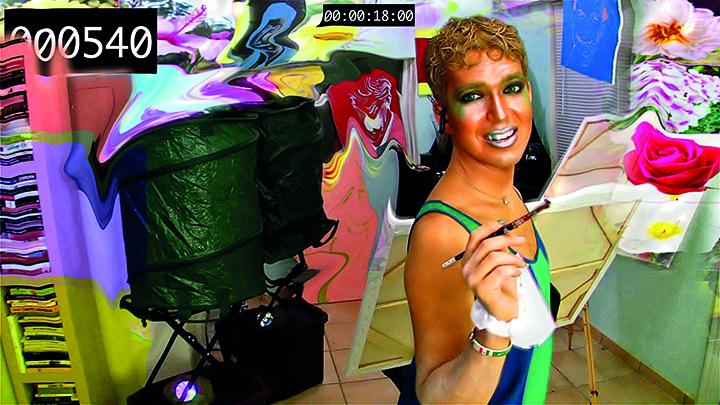

To clarify via contrast, Ryan Trecartin’s Re’Search Wait’S (2009-10), also exhibited in Melbourne, though several months prior to Henrot and at the NGV, does the opposite, and I would argue suffers for it. Ostensibly about identity and consumerism, Trecartin’s work is jarring, loud, confusing, lurid and overwhelming, which is of course the point. However, the viewer is not paralysed and overwhelmed by the onslaught of media, advertising, and technology as we are viewing Trecartin’s work. We are placated, or at the very least in denial. The reality of what is proposed to be critiqued is far more insidious, subliminal and nuanced than a gaudy mash up of screaming teens can embody.(6) Re’Search Wait’S references the reference of consumerism and the terms with which we think of it (which I would argue are obsolete), rather than activating the components to manifest an engagement such as that outlined in Grosse Fatigue. The viewers remain receivers. Consequently, the work could be said to perpetuate and emulate the very thing it attempts to critique.

Here’s one final offering from Williamson, ‘It’s in the very nature of imagery that it cannot picture a negative, No Smoking for example, without picturing a positive. A cigarette must be pictured in order for a line through it to indicate No Smoking. You can’t just show No Smoking, you would just be showing nothing.’(7) For something to become reactivated, such as egg and bacon, it requires stepping outside of the usual terms we think of the object of what is being critiqued. Perhaps the way to do this is to avoid critique being the starting point of the work. I think John Cage said analysis and creation are two different processes. Certainly, the latter begets the former. When work begins solely with critique, the imagined outcome either replicates or proposes its adversary (non smoking communicable only through smoking). I think that is where my discomfort with Trecartin’s work stems from; it embodies precisely the terms in which a critique of capitalism, media, information flow, is conceptualised. A third avenue can emerge out of exercising vulnerable processes; a gesture, a question, whim, intuition, a moment when the lightning strikes, what happens if, … call it what you will. Regardless, they are vulnerable since they do not possess the iron cladding of the tried and true motifs of repudiation. They have the capacity to present new configurations, and, in turn, will be susceptible to destruction. A writer friend of mine told me that ‘All good work must self destruct.’ There’s not as much hyperbole in that statement as you might think. Work that makes itself vulnerable, work that doesn’t, intentionally or not, flee behind signifiers of critique or irony or undermine itself by acknowledging its mechanisms, is generally more rewarding and more actively ‘critical’, even when ‘criticality’ itself seems to have become shorthand for godknowswhat.

What has emerged, I hope, reassures us that we needn’t squint to eliminate the penumbral potpourri of the spectacle, abandon egg and bacon and devote ourselves to an outdated mode of experience soaked in denialism. Perhaps, though, it is encouraging vigilance when action limps over to reflex, when meaning devolves into aesthetics and when indication of critique begets inertia. The question that is now posed is how to negotiate a shift in the production of work in which aesthetics, reflexes and tropes become active components rather than cruxes and/or placeholders. The tentative answer is that in order to do this the work may need to create its own world through what have been referred to as vulnerable processes. This is not to say that the work excludes our world, but rather offers the possibility of a new vantage point from which to speak to it.

(1) Carlos Fuentes, Terra Nostra (London: Penguin Books ltd, 1975), 324.

(2) Michael Denning, Culture in the Age of Three Worlds, (London: Verso 2004), 51

(3) Williamson proposes using the term ‘deknowing’ in the stead of denial, she describes the former as ‘active’. It suggests having to find ways not to know something once you know it.

(4) “Culture of Denial”, Judith Williamson, Frieze, podcast audio, 2008, https://frieze.com/fair-programme/listen-judith-williamson

(5) “Camille Henrot,” 20th Biennale of Sydney, last modified January, 2017, https://www.biennaleofsydney.com.au/20bos/artists/camille-henrot/

(6) Pardon the hyperbole.

(7) Williamson, “Culture of Denial”.