Yirrkala Bark Petitions and Editorial

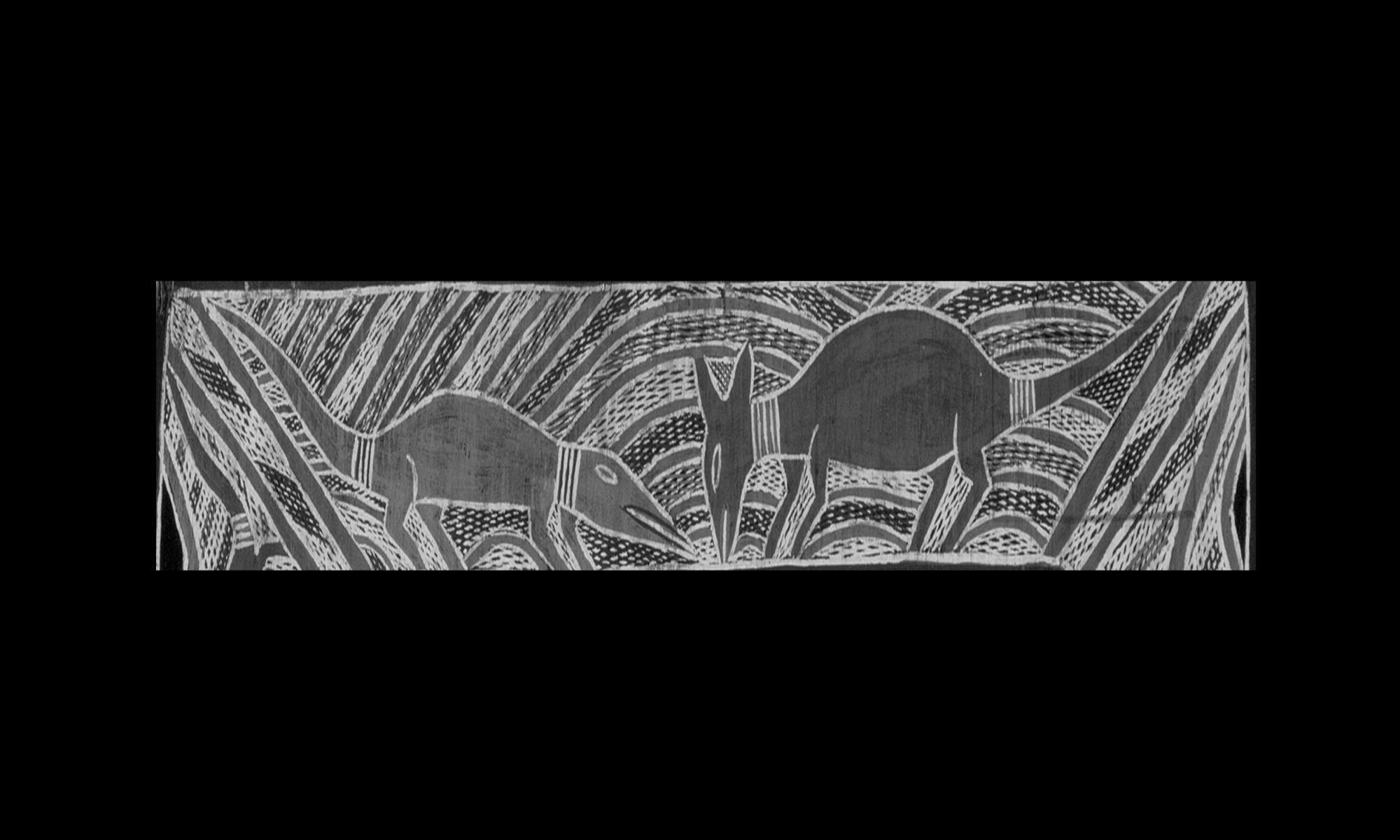

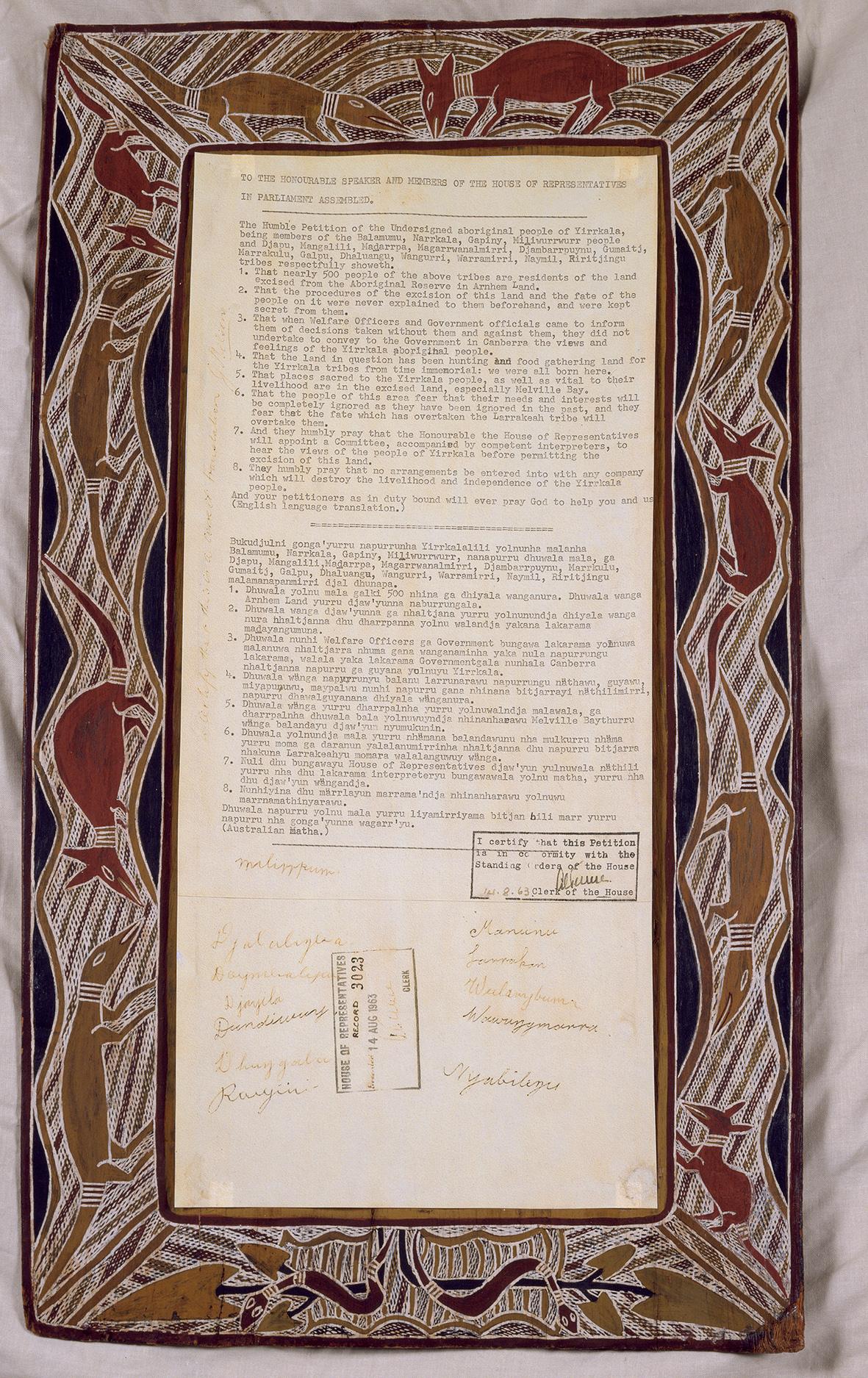

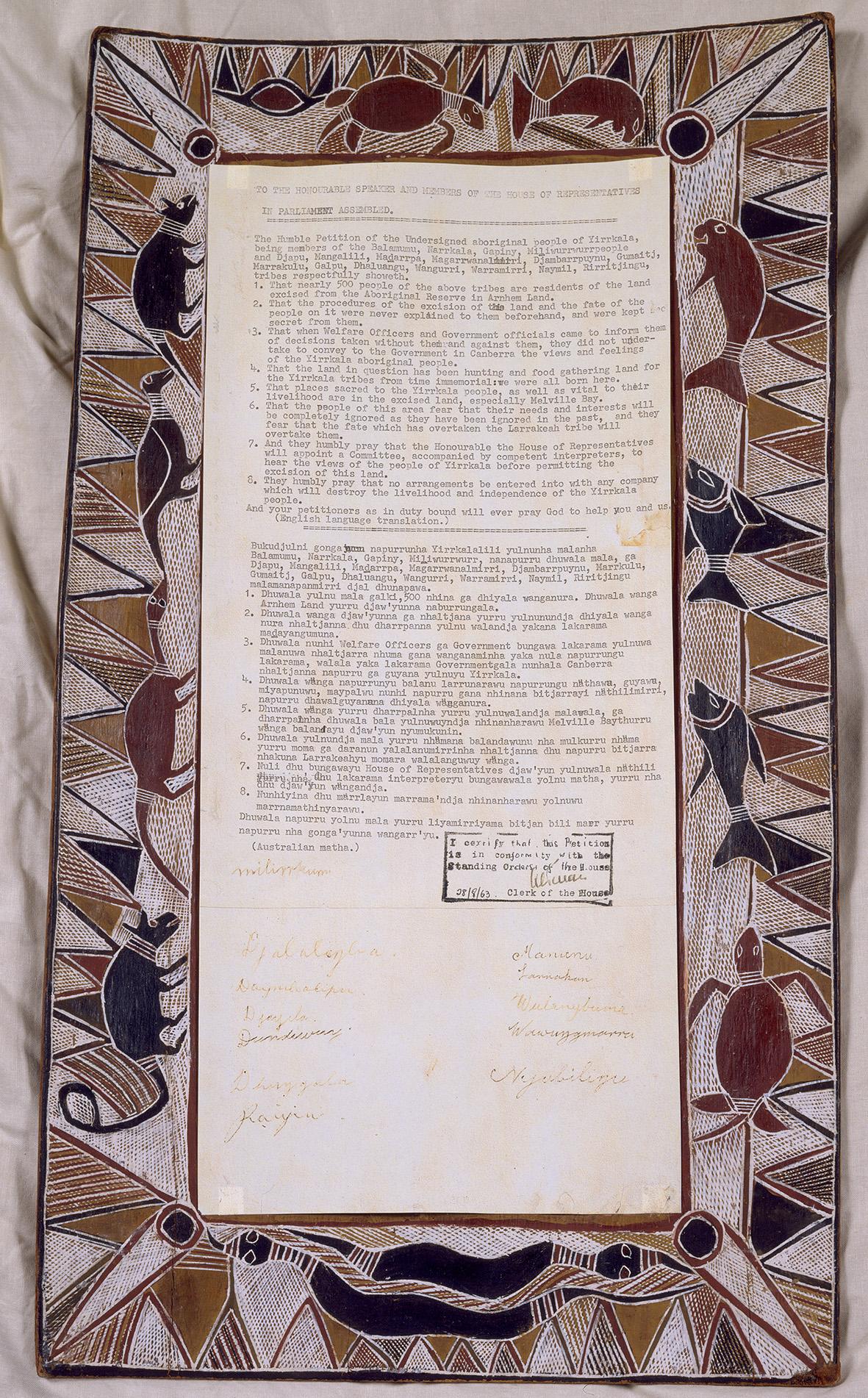

Please read the Yirrkala Bark Petitions and then scroll down to the editorial. Yirrkala artists, Yirrkala Bark Petition 14.8.1963 and Yirrkala Bark Petition 28.8.1963,

works made by Dhuwa Moiety and Yirritja Moiety respectively,

each 46.9 x 21 cm, natural ochres on bark, ink on paper, Courtesy of the Speaker of the House of Representatives, 1963.

Editorial, written by Lisa Radford in conversation with Yhonnie Scarce

After the clickbait about a man being fined for going on a Tinder date, we read the account of a group of five teenagers who also fell victim to Police discretion in deciding that their excuse; 'We wanted to see the Sunrise', was not an adequate response to their presence, just after 6am, at the Hawkesbury Heights Lookout. Seemingly insignificant, I wonder if what we are experiencing, this policing of space mediated to us via a technological apparatus signals another kind of distancing, that of a shared and collective relationship to place.

On the very same day, we read that the Australian Federal Police Officers deployed to assist in the protection of remote NT Aboriginal communities were exempted from mandatory quarantine restrictions. Rather than ask how Indigenous communities would govern themselves, we once again find the dangerous imposition of colonial-settler law. A week or two prior, our attention diverted by the burgeoning effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, the Premier of Victoria and his cabinet passed laws allowing for the resumption of drilling for cold-seam gas. (1)

I once wrote about the question of the legal standing of trees in reference to Caitlin Franzmann’s Tree-telling work that I think is worth recalling here:

Should trees have standing? is a forty-six year old essay written by Trustee Chair in Law at USC Gould, Christopher D Stone. Published in the early days of the environmental movement, Stone asks what it might mean if things we identify in nature were holders of legal rights. Based on a legal guardianship model, where things that are not able to defend themselves or do not have their own voice are allocated a watchdog as a protector, we could ask whether allowing a guardian to speak for a tree (as example) speaks more to the concept of human guilt rather than the trees pain. If we agree that caring for the environment is the right thing to do, then we need to ask how this is ensured. In one review of Stone’s essay, it is suggested that we might imagine an army of trees marching into court, shaking their branches and producing affidavits made of leaves and signed in sap. It is an interesting image, albeit somewhat silly, but reminds me of the hypothesis that should we disappear, the environment could reclaim our cities in less than 20 years. The guardianship model and the marching tree image highlight a divide and an unwillingness to see our selves as seperate to, or rather, in charge of an ecosystem—the juridification of environmental decision making. (2)

In these recent media examples, we find a collapsing of police, politics and place rendering what is wrong invisible, distant and literally at arms length, yet also contingent on and clearly in relation to an economy of place in relation to subject. These subjects do not exist in a field rendered equal by a virus, these subjects are subject unequally to the effects of the virus and the ongoing historical effects of another called Terra Nullius.

(in)solidarity.

In some ways, this editorial is a letter to Paul B. Preciado, the writer who woke up 17 days later to find the world a different place. Considering health in relation to loneliness, Paul sends a letter to a past lover. In solidarity, we are alive during a historical moment that is radically reformatting space, time, and body. This reformat is happening quickly. The many memes about time and its inability to be coherent are summed up best by the algorithmic anonymity of the meme economy. But what of our relation to social connection, risk, governance, the state and technology?

Our inability to articulate or have the ability to grasp this panorama of experience creates a delay in the signal. This delay itself is far reaching. This delay is an effect of a virus coded by bats. This vector of delay and disease creates a speculative economy of physically in search of distant anti-bodies while running a vaccine marathon. In a recently penned post titled What the virus said we read:

Take care of your friends and those you love. Rethink along with them, decisively, what a just form of life would be. Organize clusters of right living, expand them, and I won’t be able to do anything against you. I am calling for a massive return, not of discipline, but of attention. Not for the end of insouciance, but the end of all carelessness. What other way remained for me to remind you that salvation is in each gesture? That everything is in the tiniest thing. (3)

I wonder if the virus is asking us about this very unwillingness to see ourselves as part of, and instead of in charge of an ecosystem—the juridification of isolation, the further obfuscation of place and land, the ability to further render invisible that which makes us uncomfortable or challenges our way of living. Both the 'virus' and Paul, through an unusual constraint, express not only a desire and need for connection, but its omnipresence. We choose not to see connection, when it benefits us not to. We ignore the complexity of ecosystems and relations, when it benefits us not to.

Tristen Harwood eludes to this in his essay You Call it City — We Used to Live Here; a radical politics of listening and seeing, of asking questions as we now need to, is woven into his writing, initially written just a few weeks before this COVID induced coma began. Harwood is interested in that which binds us, in reclaiming knowledge, in navigating between the linearity of dominant narratives. We invited him, because navigating a relationship between the city and what we render remote is vital when considering the history of mining and nuclear energy and weapons in Australia.

In an essay about the 2016 exhibition Ua numi le fau, curated by Léuli Eshraghi, Harwood writes:

In Aboriginal practices of place-making, boundaries transform undifferentiated space into specific localities, places, home. Boundaries defined by language, cultural and sociopolitical practices, ecology, ceremony and by worldly actors who inhabit and take care of place. These boundaries are storied threads that simultaneously demarcate points of difference and coming-together, unlike dominant European boundaries, which attempt to flatten and divide space into a static gridded form—empty space apt for (European) occupation and control. Aboriginal boundaries are string-like, dividing, re-converging and weaving storied webs of connection. (4)

Harwood’s writing works to decentre dominant settler-colonial and Western epistemologies—in content and approach. In this case Harwood builds on Maddee Clark’s observations and questions in Shaking to Powder: A Response to The image is not nothing. Examining embodiment of country, Harwood cites Deborah Bird Rose where everything is moving around, trees, animals, humans, the water, inhabiting the desert, stories and history too, cosmology, all coming out of the ground. (5) You Call it City — We Used to Live Here inspects the frontier-ising of space in order for it to be dominated in 'a spectacle for development' creating a division in our relationship to place—the civilised metropolitan and the uncivilised remote. It is a division examined through the cultural production of artists—Jonathan Jones, Jimmy Pike, Jimmie Durham, Jacky Green and Lauren Burrow.

It is not only in works of art that 'the city is symbolically amputated from its multiple places of ‘economic and ecological’ maintenance’. (6) This symbolic act is very famously also found in the presentation of the two petitions to the Australian Parliament made on14th and 28th August 1963 by the Yolngu clans of the Northeast Arnhem Land in the form of the Yirrkala Barks.

Galarrwuy Yunupingu, chairman of the Northern Land Council in 1988, recounts that:

It was not an ordinary petition: it was presented as a bark painting, and showed the clan designs of all the areas that were being threatened by the mining company. It showed, in ways in which raising a multi-coloured piece of calico could never do, the ancient rights and responsibilities we have towards our country. It showed we were not people who could be ‘painted out’ of the picture or left at the edge of history. (7)

Written in both Yolngu Matha and English, the petition is rendered on painted bark boards depicting the country and protesting the excision of land from the Reserve where the Yolngu live, and hunt and where sites of significance are situated. Citing Terra Nullius, a judge in 1970 said that the Yolngu were 'an uncivilised people with no recognisable system of law', that they had no 'proprietary interest in land' and that they passed through the land rather than owning it.

‘When we paint’, Galarrwuy Yunupingu writes, ‘whether it is on our own bodies for ceremony or on the bark of canvas for the market—we are not just painting for fun or profit. We are painting as we have always done to demonstrate our continuing link with our country and the rights and responsibilities we have to it. Furthermore we paint to show the rest of the world that we own our country, and that the land owns us. Our painting is a political act.’ (8)

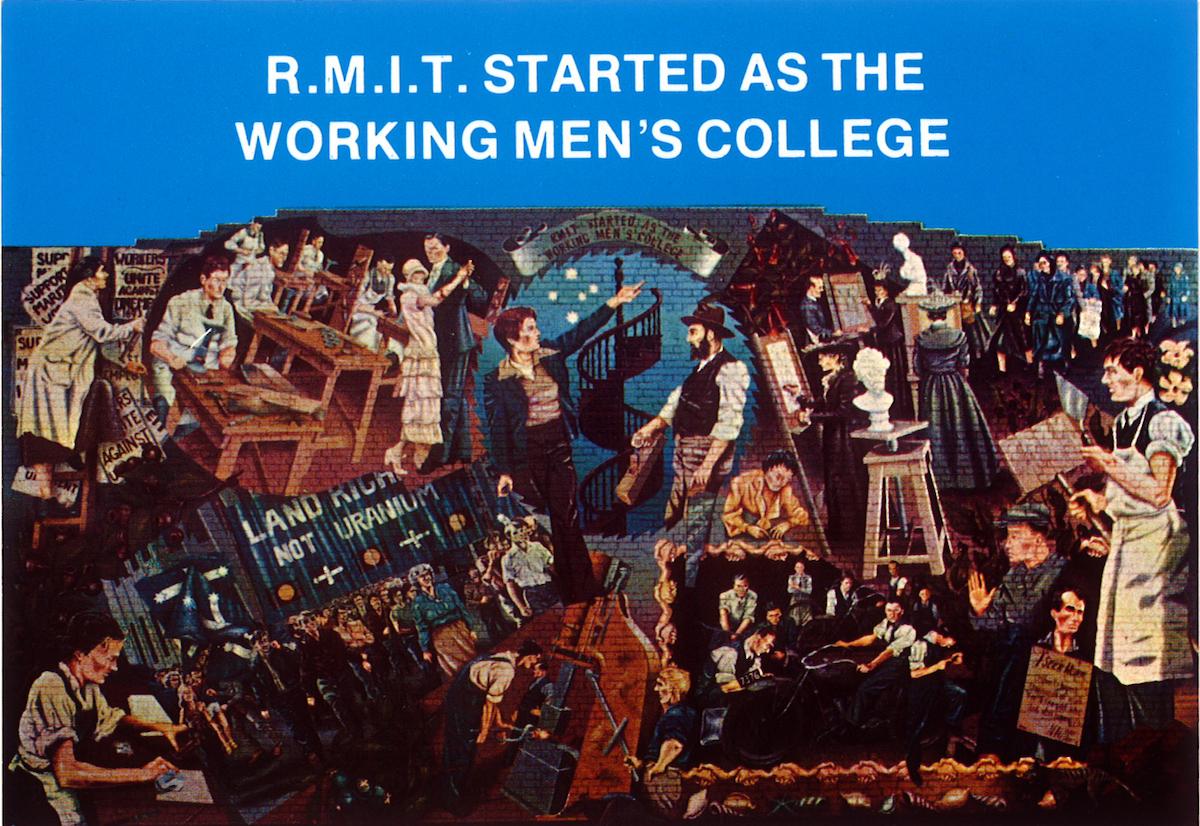

In 1978, Geoff Hogg and a collection of friends, artists and painters, began work on painting commissioned by then RMIT Student Union Arts Program officer Laurel Frank. Having studied mural painting in Mexico and Chicago, Hogg in conversation with me that the aim of the painting was to work with the origins of RMIT as the Working Men's College and connect it to contemporary life and link it to the democratic education movements of inclusion that formed part of some of the progressive thinking in the 1970’s. The wall upon which it is painted, was built in 1905 and accommodated the printing, plumbing and gas fitting trades. It now houses the RMIT Post Grad Association.

I came across the mural when on an audio walk composed by Sarah Walker, titled Dead Air—mediated by an audio play. This monologued walk comprises an in-solidarity musing of architecture, politics, place and space—calming and beautiful—the experience is almost otherworldly: positioning me in a hyper observant relationship to the world—listening with my eyes, finding a relationship among technology, the body and politics.

Hogg’s mural feels enclosed, by a mish-mash of Po-Mo additions. A narrow pathway emerges from it and exits onto Franklin Street, leading to the sarcophagus type structure which contains one of the many entries to the new metro tunnel Harwood refers to in his essay. If we look at the sarcophagus, to our right is Standing by Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheenner, the public marker and memorial to indigenous freedom fighters by Brook Andrew and Trent Walker. Looking back at the mural, a collage of histories and experiences, in the bottom left corner of the wall there is rally rendered. It looks as if it occurred near Trades Hall, also not far from this mural at RMIT, the Tunnerminnerwait and Maulboyheenner marker and the Eight Hour Day Monument. In the mural’s depiction the protestors hold a sign 'LAND RIGHTS NOT URANIUM'.

Hogg recalls the ideological hope in the mural, a collaboration born of the desire to produce something of meaning for here rather than replicating a trend. Aligning with what was once considered progressive nationalism of the late 19th century, the mural memorialises the birth of strong trade unions, RMIT as site of photography classes for women, the first in the world and a Chinese printmaker is painted as means for reflecting the diversity and cultural backgrounds of those living, working and making in this place. (9)

Terra Nullius is not merely the classification of land. As Sven Lindqvist notes, the legal fictions summed up as Terra Nullius were, and perhaps are still, used to justify the European occupation of large parts of the world. In Australia, this meant legitimizing the British invasion and accompanying acts of dispossession and genocide. This process did not stop in 1901 at Federation, in 1911 when Canberra was founded and deemed, in 1967 when Indigenous Australians were finally acknowledged in the census, or in 1986 when the Australia Act made Australian law fully independent of the British parliament.

The Yirkala Bark petitions were presented to parliament in 1963. The mural depicting the history of the Working Men’s College begun in 1978. Terra Nullius, as legal status, was not abolished until 1992.

1992.

Abolished in 1992, when finally Eddie Koiki Mabo and four other Meriam People won their 10 year battle and were finally ‘entitled to the occupation, use and enjoyment of (most of) the lands of the Murray Islands’.

Terra Nullius, is not just a law, it is an ideology and doctrine with origins in the claim that indigenous lands are empty. It has seeped into our psyche and systems evidenced in the form of interventions, agricultural practices, architecture and social policies that continue to actively separate indigenous people from each other and their lands.

The consequences of Terra Nullius affect us all—perpetuating small acts of violence and social division destroying land, culture and social bonds. Terra Nullius is a historical and empirical order that colonises the past and the future, rendering land as uninhabitable and history, unspeakable.

The ballad ‘The World Is Waiting for the Sunrise’ by Gene Lockhart and Ernest Seitz was published in 1919, just after WWI and during the last flu pandemic. (10) The teenagers replied, we are waiting for the sunrise. What the police call an excuse, is what we might recognise as a desire. A desire, albeit unconscious, for a continuing and material relationship to place begging the question: what a willingness to see ourselves as part of, not in charge of, an ecosystem look and listen like? Law is a complicated language that evolves over time. Executing changes with great haste that seem adequate in the present, as history has seen, drastically exacerbates inequity—for people and place—in the not so distant future.

1. Georgina Cue first drew my attention to the article of a man being arrested for going on a Tinder date, the other articles have appeared in the rolling effects of Covid-19 pandemic.

Alex Chapman, ‘Coronavirus fines: Man on way to Tinder date among hundreds penalised’, 7News, 13 April 2020, https://7news.com.au/lifestyle/health-wellbeing/coronavirus-fines-man-on-way-to-tinder-date-among-hundreds-penalised-c-972817; accessed 13 April, 2020

Christopher Walsh, ‘AFP officers arrived on commercial flights, not quarantined before sent to remote communities’, SBS, 12 April 2020, https://www.sbs.com.au/nitv/article/2020/04/12/afp-officers-arrived-commercial-flights-not-quarantined-sent-remote-communities; accessed 13 April, 2020

Rio Davis, ‘Gas exploration green light during coronavirus emergency 'sneaky', Victorian farmers say’, ABC, 18 March 2020, https://www.abc.net.au/news/2020-03-18/farmers-label-decision-to-lift-gas-ban-under-coronavirus-sneaky/12066000; accessed 18 March, 2020

2. Lisa Radford, ‘Caitlin Franzmann: Treetelling’, un-extended, reviews, 26 February 2018, http://unprojects.org.au/un-extended/reviews/caitlin-franzmann/; Accessed 14 April 2020.

3. https://lundi.am/What-the-virus-said, accessed 27 March, 2020.

4. Tristen Harwood, ‘Love and Decolonisation in actu’, un Magazine, issue 10.2, 2016, http://unprojects.org.au/magazine/issues/issue-10-2/love-and-decolonisation-in-actu/ accessed 15 April, 2020.

5. Deborah Bird Rose, Dingo Makes Us Human, Life and Land in an Aboriginal Australian culture, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1992, p. 57 in Tristan Harwood, You Call it City - We Used to Live Here, A + A online, April, 2020.

6. Tristan Harwood, ‘You Call it City — We Used to Live Here’, A + A online, April, 2020.

7. Galarrwuy Yunupingu, ‘Painting is a political act - 1988’ in How aborigines invented the idea of contemporary art: Writings on Aboriginal Contemporary Art, edited by Ian MacLean, IMA, Brisbane, 2011, p. 89-91.

8. Galarrwuy Yunupingu in ibid, p.90.

9. Notes from a facetime conversation with Geoff Hogg, April 11, 2020.

10. Dear one the world is waiting for the sunrise

Ev'ry rose is covered with dew

And while the world is waiting for the sunrise

In my heart is calling you

Dear one the world is waiting for the sunrise

Every little rose bud is covered with dew

And my heart is calling for you

The thrush on high his sleepy mate is calling

And my heart is calling you

In this song, love is mediated by an ecosystem.

Here are some Waiting for the Sunrise links to love with. https://www.lyrics.com/lyric/911084/The+Legend+and+the+Legacy/The+World+Is+Waiting+for+the+Sunrise Benny Goodman, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nZazFYqtQC0. Les Paul and Mary Ford https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=7iGXP_UBog4 Willie Nelson https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=TI3r7QyPspQ Cal Perkins & George Harrison

https://youtube.com/watch?v=BXxO Bing Crosby https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SFek-kVtTfk

Exhibition curated by Lucina Lane https://tcbartinc.org.au/content/the-world-is-waiting-for-the-sunrise/