The Mirror

EditorialAboutA+a Study CentreA+a ArchiveShopClose Menu

The Radicle Root

The radicle is the first root that grows when a seed germinates—it forges a path into the soil and anchors the fresh life in place. This first root is vital, but only insofar as it allows for all the generative processes that follow. The radicle represents an unstoppable process among innumerable unstoppable processes, living energies collaborating with each other as the new plant grows and interacts with the matter around it (both living and inert).

Before the plant dies, it will have reached some sort of expanse. This could be as grand as a two-hundred-year-old blue gum or as modest as a paper daisy. Death can come prematurely through harvesting, dehydration or infection, or it can happen at a proper time, when cell replacement slows and finally stops, a process known as senescence.1 While the radicle, the first root, represents a beginning, there is never an end to these growing stories. The material of the plant is reborn through processes intuitive to the living things of the planet.

Radicle Notes is an online publication comprising accounts—including essays, diaries and video compositions—born out of the Dookie Art + Ecology Residency, which was launched by the Centre of Visual Art (CoVA) at the University of Melbourne in early 2022.2 All the contributions to this publication have come from artists who undertook the three to four week residency at the University’s Dookie campus, an agricultural teaching and research facility and working farm located near Shepparton in regional Victoria, on Yorta Yorta Country.3

...Residencies and Root Systems

‘Radicle’ is a valuable concept to frame the contributions enclosed here. While creative residencies facilitate limited durations of experience and exploration, they inevitably trigger a profusion of subsequent journeys into ideas and connections which can’t be foreseen. The unusualness of the durational context—the out-of-the-ordinary setting—inevitably sparks fresh energy in the residency participant. Strands of new experience start to branch outwards and dig down, looping and twisting to form a network stemming from the initial moment of encounter: the start of the residency. For the individual artist, these new strands grow alongside the already energetic networks of their existing practice and, in turn, affect the practices and thinking of other individuals they encounter through the residency. One root can lead to many roots, then to root systems, and even ecosystems. Likewise, one residency can start a whole new line of enquiry for an artist which may deeply affect their future practice.

The contributions to this publication represent the first roots to grow from the Art + Ecology Residency at Dookie campus in 2022, and each contribution is mentioned in more depth below. Some new strands of practice not captured in this publication include works developed as part of the residency and subsequently exhibited both nationally and internationally. These include George Egerton-Warburton’s three sculptures Woozy heights, Write-off and Gut fugitive (2022), which were exhibited in Melbourne Now at the National Gallery of Victoria in 2023 and works by Lauren Berkowitz, George Egerton-Warburton, Paul Fletcher and Jen Valender which were included in the exhibition Always and Altered co-developed by Benalla Art Gallery, Winton Wetlands and the Centre of Visual Art in 2023.4

These emerging root systems of collaboration and knowledge-making relate not only to the practices of the individual artists who stayed at the Dookie campus. A new suite of projects exploring the intersection of community resilience, creativity and common ground also developed through the process of setting up a creative studio at the agricultural campus, with several valuable outcomes.5 These still growing root systems of creative practice have emerged from a series of simple encounters and initial conversations as part of the Art + Ecology Residency.

Radical Change

Radicle is also a helpful term to use to frame this publication because of its homophonic associations. To be radical is to be the cause of great change.6 In the context of our social-ecological conditions in the early twenty first century,7 it appears that great change is exactly what we need—even if the change is back to practices almost as ancient as our species, as in the case of Indigenous Australian traditions of caring for Country.8

For a start, great change is here whether we like it or not. It must be accepted that we do not live on the same planet as did our relatively recent ancestors during the Enlightenment, at which point the accepted terms of Western learning models were torn from religious dogma to be instead secured to anchors of strict categorisation and rigorous experiment. The systems and measures put in place to designate what is acceptable (read: provable) knowledge around that time speak to a different Earth than the one we live on now.

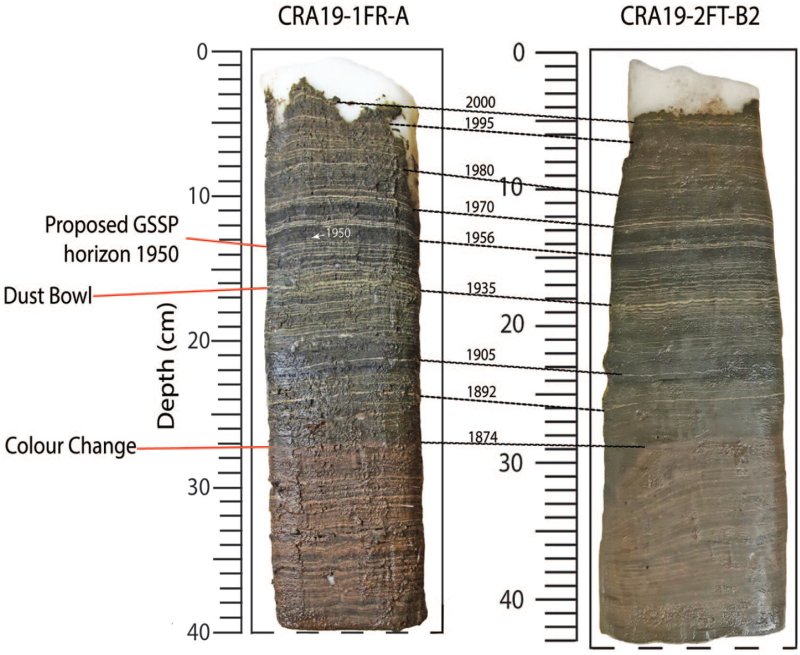

Humans have changed the planet irrevocably through our collective initiatives since the 1950s. In 2023, an interdisciplinary research group known as the Anthropocene Working Group, set up in 2009, released details of a proposed site marking the beginning of the new epoch in the planet’s geologic timeline, the Anthropocene.9 This marks the end of the previous epoch, a relatively stable period in Earth’s climate conditions which lasted approximately 11,700 years known as the Holocene. In July this year it was announced that the group had selected Crawford Lake in Ontario, Canada, as the site which best represents, in layers of sedimentary evidence below the water, humanmade physical, chemical and biological contamination in the Earth’s surface since the mid-twentieth century.10 These contaminants include radioisotopes from thermonuclear weapons testing, carbonaceous particles originating from the burning of fossil fuels, and of course microplastics. Supporting evidence at this site also includes massive and rapid biodiversity loss.

As Professor of Micropaleontology Alejandro Cearreta noted in a recent article in The Conversation: ‘The Anthropocene is part of geologic time. Formalizing it precisely will help determine its meaning and use in all sciences and other academic disciplines.’11 Identifying the place of a new epoch may prove momentous for practitioners in the arts as much as the sciences. Our work going forward, past a formalised identification of the new epoch, is to address the interrelatedness of factors that have gotten us to this point—not from the perspective of siloed disciplines, but through shared conversations and research across the sciences, arts and knowledges held in communities. We can’t possibly proceed as individuals and meet anything like success in our attempts towards social-ecological adaptation; instead, we need to proceed as a mutually accountable network of contributors.

In 2020, the art historian TJ Demos published a very good question for us to consider as we seek new pathways forward: ‘Where are the rift zones between destructive and wholly unjust if not quite outmoded ways of organising existence—within petrocapitalism, colonialism, anthropocentrism, sexism, and white supremacy—and alternative practices, narratives, and visions founded on social justice and radical multispecies flourishing, glimpsing decolonized futures of environmental sustainability?’12

Drawing on Demos’ question, the concepts of ‘social justice’ and ‘radical multispecies flourishing’ will structure the remainder of this editorial, and help to introduce our contributors.

The Artist’s Critical Stare: Towards Justice

We can now see that we have, intentionally or not, induced massive change on this planet, and we need radical changes in the ways we live, learn and research if we are going to adapt to these new conditions. And drastically limit further damage. This is something artists, including those featured in this publication, can help us with.

Social justice, including economic justice, is something many environmentalists identify as necessary for environmental sustainability. We can clearly see that settler colonialism and runaway capitalism have fed the Anthropocene. Yet, if we are seeking a better system to exist in, too often justice is only achieved through activism and redressed action—not through proactive or voluntary good-will on the part of legislators. The contributions of artists to public discourse are often the most radical, agitating and provoking of all voices, hell bent on raising awareness of crises and injustices.13 Of course, not all art interacts with issues relevant to politics and policies of the time, but when it does it can lock us with a deeply critical stare. So, if we need great change, or radical action, we certainly want artists around to agitate us out of our everyday malaise.

In a new essay for Radicle Notes titled Dirty Horizons: A Queer Cosmogeny of Soil, Luna Mrozik Gawler engages their investigations and reflections from the Art + Ecology Residency around the dirty topic of soil. Soil as polluted, soil as underestimated and misunderstood. In Gawler’s words, ‘Soil is inherently queer. Queer in its capacity to perpetually shift forms (queue clay, dust, peat, marl) to refuse static definitions (queue dirt, sod, turf, humus), to resist containment, and to be so committed to morphological freedom that it liberates and transmutes all others that encounter it (queue compost).’ In reading Gawler’s essay, we might realise—as we do on hearing about Crawford Lake and the new geological epoch—that the Earth is no longer something which is beyond our bodies. We need intersectional and queer positionings to revisit the demarcations, binaries and dismissals of outmoded Western knowledge systems.

Artist Emily Simek and scientist Rose Faragher collaborated on the Art + Ecology Residency in 2022, using the specificity of the season of their stay at the agricultural campus to participate in the grape harvest. For Radicle Notes, Simek and Faragher propose a discussion around waste and privilege as participants in an investigation (or as artists on a residency) related to the ‘waste’ materials produced during the harvest. Capitalist logic is interrogated in their generous reflection on the roles of host and guest, on my perspective (whoever that is) and their perspective (irrespective of species or material).

George Egerton-Warburton’s work as part of the Benalla Art Gallery exhibition Always and Altered in many ways defies summarising. And therein lies its great value in this consideration of our shared environmental futures. If one of the lures of contemporary consumer culture is to provide us with a palatable story to consume and shape our lives around—a story which reflects an easy, anthropocentric perspective rather than the multi(species) perspective—in advocating for a new way of measuring value and meaning, which strives for positive social-ecological modes of operating, the inscrutable message has a lot to say. Egerton-Warburton’s work comprises objects which are partly salvaged, partly found, partly stolen. Looking at the work, an interrogation of economic injustice whispers through in bundled-up underpants, soft puffs of fleece and an immense engine hoist frame.

Empathy Stories: Towards Radical Multispecies Flourishing

The cause of great change need not be confrontational, but it likely needs to say something that is not being said, or not said strongly enough. The act of telling a new story. Each of the contributions to Radicle Notes say something new in its own way, each one tells a story grown from the experiences of the artist as they explored the residency space, its inhabitants (human and non-human) and the agricultural activities they encountered. The stories told by artists offer abnormal insights into the experiences we often designate normal, which in turn ask us to consider who we are and what we might do next. As anthropologist Anna Lowenhaupt Tsing notes, ‘To listen and tell a rush of stories is a method. And why not make the strong claim and call it a science, an addition to knowledge?’14

Jen Valender presents a contemplative likeness of her experiences at the Dookie campus in Radicle Notes, considering side-by-side both the absurdity of the commodification of other animal species (such as cows) identifiable in an agricultural setting and the absurdity of creative practice through the eyes of the author. In practicing and articulating endurance performance, Valender activates a vital component of empathic exercise—one which almost every human has struggled with at some point in watching the news or seeing a tragic scene in front of them: we must suffer to know empathy. Through her considered actions in a creative space, she invites an intimacy with species beyond our own.

Tina Stefanou is a PhD candidate in the Faculty of Fine Arts and Music at the University of Melbourne and her practice ‘engages in sound as social practice and explores with and beyond … the more-than-human voice.’15 Her time at the Dookie residency aggregated in blended spheres of connections across the human-led networks of the regional campus and its surrounding communities, as well as the more-than-human relationships held in the campus environment. Stefanou uses the urgency of onomatopoeia to get us into the zone of physical experience she accessed on the farm: THUD! … SLAP! … CLUNK! These are the articulations of intimacy ordinarily available between humans and other animal species in our shared agricultural spaces; the question for me after reading Stefanou’s piece for Radicle Notes is: do we want this to change?

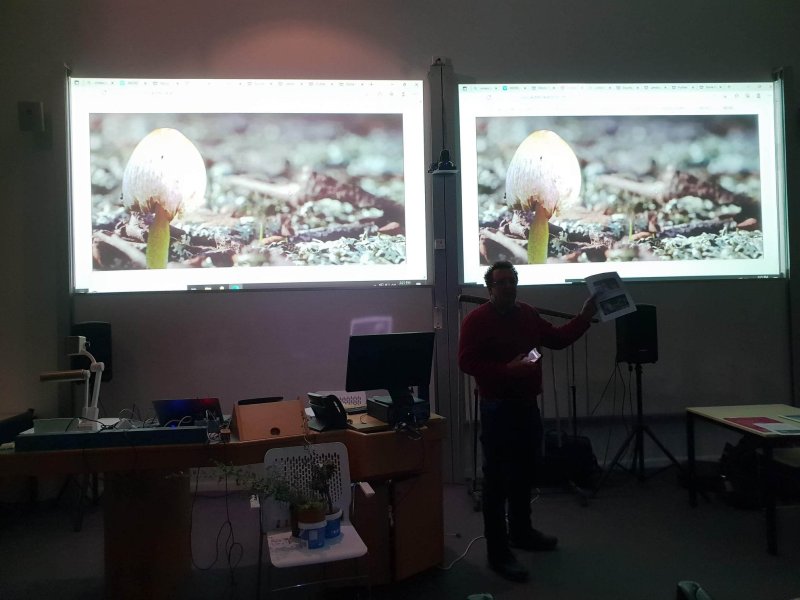

Paul Fletcher’s multilayered video work Planted shifts our attention for a fixed duration from the analytical to the sensory. An experience of feeling into the interconnected rhythms and textures of bushland around the Dookie campus is offered—analysis is seemingly suspended for six minutes and we sit with abstracted forms and sounds of sites he walked through on the residency. Using emerging technologies for capturing electric data from plants, data is ‘converted to midi-electronic music note pitches, timing and volume’ and offered as aural pulses in dialogue with visual landscapes and abstract forms.

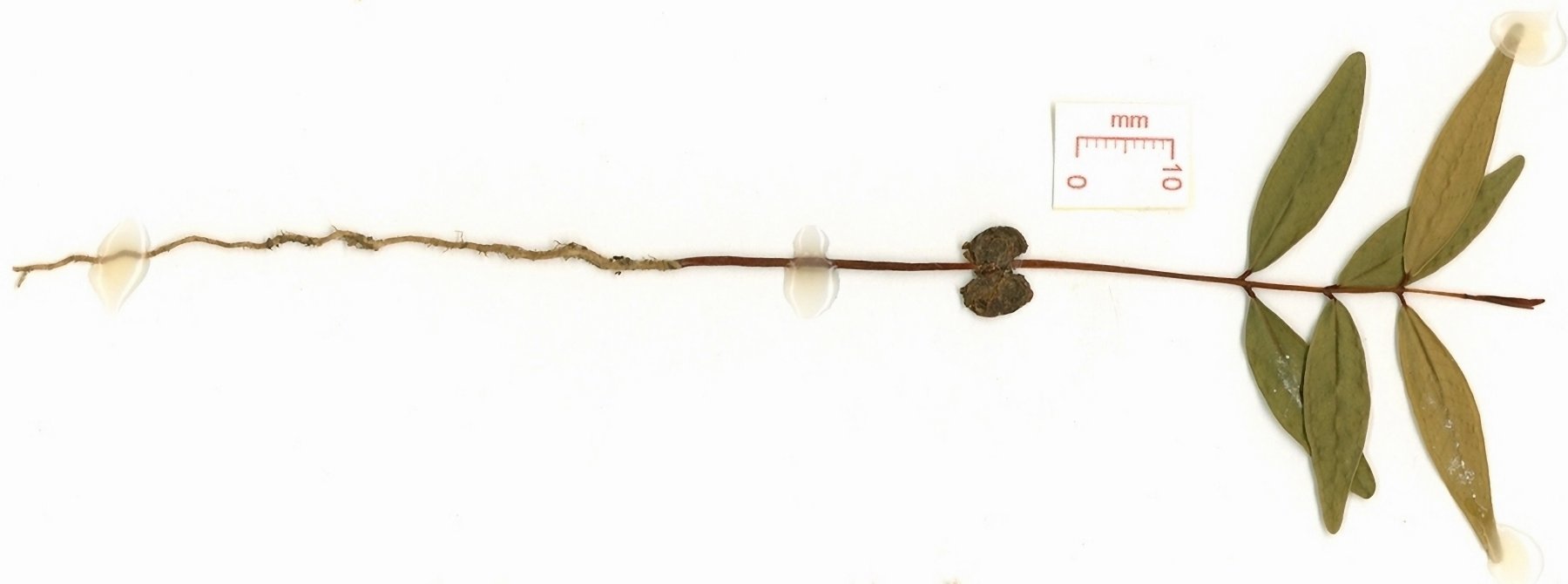

To conclude Radicle Notes, Lauren Berkowitz offers a diary of her days spent on the residency, providing insight into her processes and encounters; as well as her thinking through of the complexities (human and more-than-human) as a new work takes shape. The diary traces the first moments of her new sculpture Remnants (2022-23), which emerged as she walked across the campus and surrounding area—a work installed first at the Dookie campus when her residency concluded and subsequently re-installed with local botanical adaptations at Benalla Art Gallery in 2023.

Accompanying this artist diary, I contribute a reflection on my own experiences of de-installing Remnants at the campus after the artist had returned home following her residency—a process which revealed to me more than ever the irrevocable entanglement of natural and synthetic forms in our world. Teasing apart light strands of old tarp from the frayed roots of dead weeds, I was met with something akin to a Crawford Lake moment, but without the clear stratification of evidence. It was a holistic mess, and I felt moved to love it, rather than to turn away.

Radicle Growth Moment

As I write this editorial, the planet looks to be headed for El Niño—the last El Niño event saw some of the worst droughts and bushfires in Australia’s history.16 Warming temperatures on the planet will only exacerbate things, and the longer we participate in carbon-heavy and fossil fuel industries, the hotter it’s going to get. But here’s the rub. Hands up who used petrol this week, or ate three serves of meat in one day? If we are going to mitigate the effects of climate warming and reduce environmental damage in the future, we need radical responses. We need to change the ways we live and grow. And we need to demand that our public policies hold industries to a radical new standard in support of long-term planetary care.

Learning from the artists who have contributed to this publication, it is clear that even the simplest action, the radicle growth moment, can launch a new root system of positive actions—a network of affects and a space of collaboration beyond the individual—which may be something that we need to live better as social-ecological participants.

I conclude this editorial by acknowledging that the Dookie Campus is situated on the Traditional Lands of the Yorta Yorta people, and I pay my respects to their Elders past, present and emerging.

1. “Senescence (from the Latin word “senēscere”: to grow weak, become exhausted, and to be in a decline) generally refers to the process of growing old and is associated with decay and mortality or decreased fertility with age [1], but it is actually a very widespread concept for plants. Plants have specific characteristics that violate the general, classical definition of senescence… Besides age-dependent/developmental senescence, environmental conditions can also trigger senescence, and it has been shown that the timing and rate of senescence is highly affected by environmental cues such as photoperiod, temperature, and moisture in soil.” Miryeganeh, M., ‘Senescence: The Compromised Time of Death That Plants May Call on Themselves’, Genes 2021, 12(2), 143, https://www.mdpi.com/2073-4425/12/2/143.

2. CoVA, Art + Ecology Residency 2022, https://sites.research.unimelb.edu.au/cova/projects/exchange-programs/art-and-ecology-residency.

3. Dookie Campus: History, https://science.unimelb.edu.au/about/our-locations/dookie/history.

4. Always and Altered, Benalla Art Gallery in collaboration with Winton Wetlands and the Centre of Visual Art (CoVA), 4 Aug to 17 Sept 2023, https://benallaartgallery.com.au/always-and-altered/.

5. Fraser et al, Living Art, Melbourne: Centre of Visual Art, 2023; ‘Creativity & Community Resilience Studio’, https://sites.research.unimelb.edu.au/cova/research/art-and-science/projects-2020/creativity-and-community-resilience-studio, 2021-23.

6. “Radical/ˈradɪkl/adjective. 1.(especially of change or action) relating to or affecting the fundamental nature of something; far-reaching or thorough. 2.advocating or based on thorough or complete political or social change; representing or supporting an extreme or progressive section of a political party.” Oxford Languages, https://languages.oup.com/google-dictionary-en/, accessed 26/08/23.

7. “Humans are a fundamental part of ecosystems and rely on them to support a wide array of their needs. The extent of environmental stressors connected to human activities thus makes understanding social–ecological linkages of central importance for the analysis of almost any action related to securing a sustainable future.” Barnes et al, Social-ecological alignment and ecological conditions in coral reefs, Nature Communications volume 10, Article number: 2039 (2019), https://www.nature.com/articles/s41467-019-09994-1.

8. “The Western concept of Australia as wild and untamed wilderness is also overturned, the evidence showing it to be a mosaic of management constructed by Aboriginal people and not simply by climate.” Neale, M. ‘First Knowledges’, in Cumpston, Z., Fletcher, M.S. and Head, L., Plants: Past Present and Future, Port Melbourne: Thames and Hudson, 2022, p. 4.

9. ‘Spot marking the beginning of the Anthropocene identified by UCL researchers’, UCL News, https://www.ucl.ac.uk/news/, 14 July 2023.

10. Cearreta, A., ‘A Canadian lake holds the key to the beginning of the Anthropocene, a new geological epoch’, The Conversation, 12 July 2023, https://theconversation.com/a-canadian-lake-holds-the-key-to-the-beginning-of-the-anthropocene-a-new-geological-epoch-209576.

11. Cearreta, A., ‘A Canadian lake holds the key to the beginning of the Anthropocene, a new geological epoch’, The Conversation, 12 July 2023, https://theconversation.com/a-canadian-lake-holds-the-key-to-the-beginning-of-the-anthropocene-a-new-geological-epoch-209576.

12. Demos, TJ., Beyond The World’s End: Arts of Living at the Crossing, Durham: Duke University Press, 2020, p. 2.

13. “Art activists do not want to merely criticize the art system or the general political and social conditions under which this system functions. Rather, they want to change these conditions by means of art – not so much inside the art system but outside it, in reality itself.” Groys, B., ‘On Art Activism’, e-flux Journal #56, June 2014, https://www.e-flux.com/journal/56/.

14. Tsing, A. L. The Mushroom at the End of the World: On The Possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins, Princeston: Princeton University Press, 2015, p. 37,

15. ‘Tina Stefanou: 30 May to 1 July 2022’, https://sites.research.unimelb.edu.au/cova/projects/exchange-programs/art-and-ecology-residency/2022-residents/Tina-Stefanou.

16. Climate Council, ‘He’s Back: What the Return of El Nino Means’, 19/09/23, https://www.climatecouncil.org.au/resources/what-the-return-of-el-nino-means/.

Author/s: Suzanne Fraser

Suzanne Fraser. “Radicle Notes: Editorial.” Art and Australia.com https://artandaustralia.com/A__A/p165/radicle-notes-editorial

Art + Australia Editor-in-Chief: Su Baker Contact: info@artandaustralia.com Receive news from Art + Australia Art + Australia was established in 1963 by Sam Ure-Smith and in 2015 was donated to the Victorian College of the Arts at the University of Melbourne by then publisher and editor Eleonora Triguboff as a gift of the ARTAND Foundation. Art + Australia acknowledges the generous support of the Dr Harold Schenberg Bequest and the Centre of Visual Art, University of Melbourne. @Copyright 2022 Victorian College of the Arts The views expressed in Art + Australia are those of the contributing authors and not necessarily those of the editors or publisher. Art + Australia respects your privacy. Read our Privacy Statement. Art + Australia acknowledges that we live and work on the unceded lands of the people of the Kulin nations who have been and remain traditional owners of this land for tens of thousands of years, and acknowledge and pay our respects to their Elders past, present, and emerging. Art + Australia ISSN 1837-2422

Publisher: Victorian College of the Arts

University of Melbourne

Editor at Large: Edward Colless

Managing Editor: Jeremy Eaton

Art + Australia Study Centre Editor: Suzie Fraser

Digital Archive Researcher: Chloe Ho

Business adviser: Debra Allanson

Design Editors: Karen Ann Donnachie and Andy Simionato (Design adviser. John Warwicker)

University of Melbourne ALL RIGHTS RESERVED